Worried about Your Home Surviving the Next Disaster?

Image: Joseph Laney

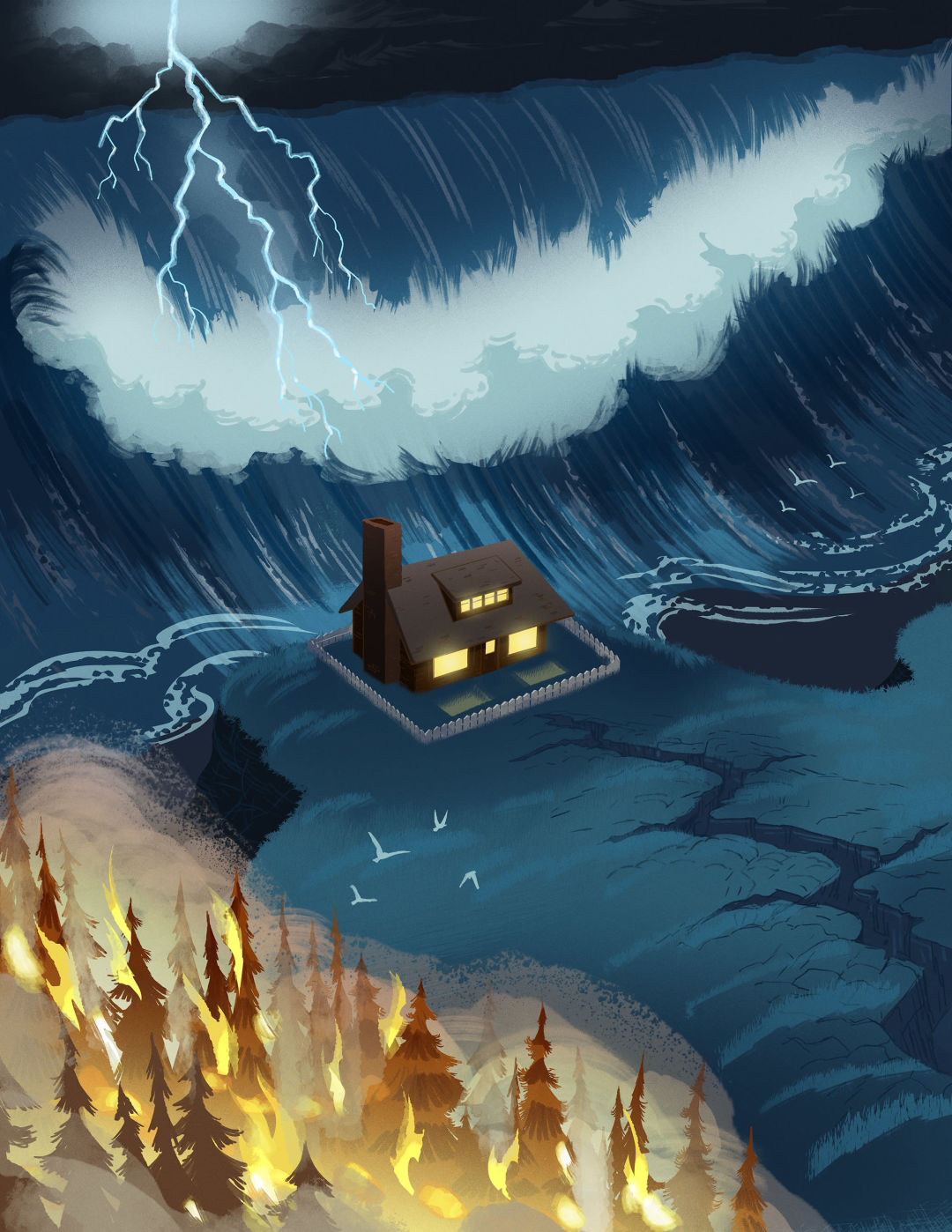

Maybe it’s out there somewhere. A cross between Superman’s Fortress of Solitude and the brick house from “The Three Little Pigs.” An ultimate, unbreakable Super House. Surely, given predictions of a massive Cascadia Subduction Zone earthquake (and resulting coastal tsunami), not to mention our already-arrived age of wildfires, a local architect or entrepreneur has dreamed one up. After all, Oregon State University’s wildfire risk map estimates that half of the state’s 1.8 million tax lots are at risk.

Such a Super House would have to be flexible enough to shake with the ground yet, if on the coast, also robust enough to withstand tsunami-born flooding. It would be clad in fireproof material and give way to a strategically landscaped exterior. But how much of this imaginary home is rooted in reality—or, frankly, even necessary?

“There are a number of ways of thinking about a truly resilient house,” says Jay Raskin, an architect and resilience expert who has chaired the Oregon Seismic Safety Policy Advisory Commission and coauthored the Oregon Resilience Plan. “One is the heroic approach: doing everything for your individual house. Another is as part of a resilient community.”

Despite all he’s learned in his 30-year career, Raskin himself lives not in some far-flung, high-tech residential fortress but a 1925 Craftsman-style house in Southwest Portland. Before purchasing it, he investigated the site’s potential for landslide and flooding, paid to have the house tied to its foundation, switched to all-electric utilities (no potential for gas explosions), purchased earthquake insurance, and stocked up on emergency supplies. He also recommends paying attention to whether your town or city has seismically upgraded its critical lifeline infrastructure (water, essential facilities, bridges) and has a good emergency response system. Portland is “not there yet,” according to Raskin, but moving toward it.

Laura Squillace, codirector of design for sustainable Portland design-

construction firm Green Hammer, is of the same view: although it would vary from house to house, many homes would remain standing when the Big One hits. “My single-story, wood-framed 1943 home in Portland, since it’s not in a liquefaction zone, is going to be just fine as long as it doesn’t fall off my foundation,” Squillace says, noting that some construction types are inherently flexible. There would still be damage, she says, but not catastrophic damage. “And that is really simple,” she says, noting that it didn’t cost a ton to have her foundation bolted down.

She also added 80-gallon tanks for drinking water and a seismically activated gas shutoff valve, upgraded the mechanical system’s filters in anticipation of future wildfire smoke, and keeps two weeks of food supplies on hand. And she made a point of getting to know her neighbors.

Even if your home survives, it’s just the beginning in a natural disaster. “When we talk about resilience, we talk about the ability to bounce back as a community,” explains Erica Fischer, an Oregon State University engineering professor, who has visited disaster sites around the world to study successful approaches to resilience. “If you don’t have access to an emergency room, or schools, or a grocery store, are you going to stick around?”

When Paradise, California, lost most of its nonresidential buildings to wildfire in 2018, the population declined by 90 percent. But there can be significant loss even when the actual damage is far less. Fischer says that ideas around resilience shifted after the 2014 South Napa earthquake. The event showed that recent retrofitting practices for unreinforced masonry buildings are working—but while many such structures were relatively unharmed, neighboring buildings that weren’t retrofitted saw damage that caused people to leave or businesses to close, affecting the whole community. “This changed the way the earthquake science field examined the concept of resilience—that it cannot be on a building by building scale.” The question for city planners, Fischer says, is what level of loss can a community weather to continue functioning economically and socially? “Because the answer can’t be zero.”

Fischer, like Raskin and Squillace, lives in an older house: a 1930s bungalow in Corvallis. She still worries about disasters, but she knows her home’s vulnerabilities, and she has a plan: “My house is bolted to the foundation,” she says. “I have my friends who are really good at growing food and have bought their crank-radios. These are the places I’m going.”

Some home features intended for convenience or cost savings can also make post-disaster recovery easier. Squillace’s company Green Hammer specializes in building houses and multifamily projects to the Passive House standard, which reduces heating and cooling costs with added insulation and triple-pane windows. In a natural disaster, when utilities might be out for days or weeks, these houses will stay more comfortable. “You really want to not just be solving for one problem, but in a way that’s also giving you everyday benefits, and that will make your house stable,” Squillace says.

The same goes for solar panels and water. Today, solar panels are more affordable and useful than ever, and the investment can pay for itself even if there’s not a disaster. Decorative landscaping features, like a pond on your property, can be a sudden water source. “You want something nice or useful for daily living, and then guess what: it helps when something bad happens,” Raskin says, though pond water wouldn’t be potable without a certified water filter.

There are those who subscribe to the third-little-pig school of thought, building extra resilient when their neighbors aren’t—although not to the same extent as that unshakable Super House.

The ultimate preventive measure would be base isolation, traditionally used not for houses but for important civic buildings and commercial towers. It basically acts as shock absorbers for your foundation, allowing a house to move independently from the under slab. “The house stays still while everything else goes back and forth,” Squillace says. “We do it all the time on skyscrapers.” The new Oregon State Treasury building in Salem has them. Similarly, rocking shear-wall technology, like at Oregon State University’s Forest Science Complex, is generally reserved for tall buildings and for hospitals and other critical facilities, although a structural engineer can help overachieving homeowners reach the higher standard.

In hurricane-prone regions, architects draw on simple geometry to create resilient houses: concrete domes, or rounded structures like those made by Asheville, North Carolina–based Deltec Homes. The less elongation of a house, the better. “A square box is the simplest and strongest; a dome, same basic idea,” Raskin says. “But if I build an addition to that box and make it an L-shape, where those two pieces meet becomes the weakness.”

Tsunami resilience means accounting for not only earthquakes, but water, too. Take the Tsunami House, located in a high-velocity flood zone on Camano Island in Washington’s Puget Sound. Built on pilings, its main living level was located nine feet above grade. The lower level, dubbed the “Flood Room,” has walls that can break away in a storm surge while the columns keep the upper levels standing. “The structure has to stay rigid,” explains the home’s designer, Dan Nelson of Designs Northwest Architects.

The other major natural disaster, of course, is wildfires. Thankfully, this can involve reasonably affordable choices. For a house Green Hammer is currently designing in wildfire-prone Wallowa County in Northeastern Oregon, the homeowners decided against an integrated indoor-outdoor sprinkler system. “It was a pretty big price tag, with a lot of questions,” Squillace says. “When do you turn it on: when the fire is already there, or are you presoaking? Do the utilities already melt before the sprinklers can even activate?”

Squillace’s clients instead decided on resilience measures with secondary benefits. The home’s metal roof, built without any soffits under the overhang (a wildfire weakness) requires minimal maintenance. Metal wall panels would be just as resilient, but her clients decided against them due to their large carbon footprint, instead opting for cedar siding with a nontoxic, fire-resistant coating. Landscaping will follow Firewise USA standards, including cutting trees and shrubs near the house. “You’re starting to see this when you drive through rural areas, this perimeter of defensible space,” Squillace says. “It’s an adjustment of what people think is beautiful sometimes, because they’re used to a lot of vegetation around their homes.”

If “The Three Little Pigs” teaches an incomplete lesson about disaster resilience—build robustly, but go it alone—consider that over time there have been different versions of the story. Sometimes the first two pigs survive when the Big Bad Wolf blows down their straw and stick houses; they safely join the third pig behind the brick. There’s even a 1993 book by Eugene Trivizas called The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig, wherein predator and prey make peace in a house of flowers.

Maybe building with begonias is far-fetched compared to base isolation and a metal roof. But if there’s one overriding message coming from architects and resilience experts, it’s that there’s a reason no one’s built an ultimate Fortress of Safe-itude. It’s not just expensive, but it risks losing the bigger picture. For true, everlasting resilience, you might be better off in Clark Kent mode: centrally located, well prepared, and better connected.