Fixing Portland? They’re on It.

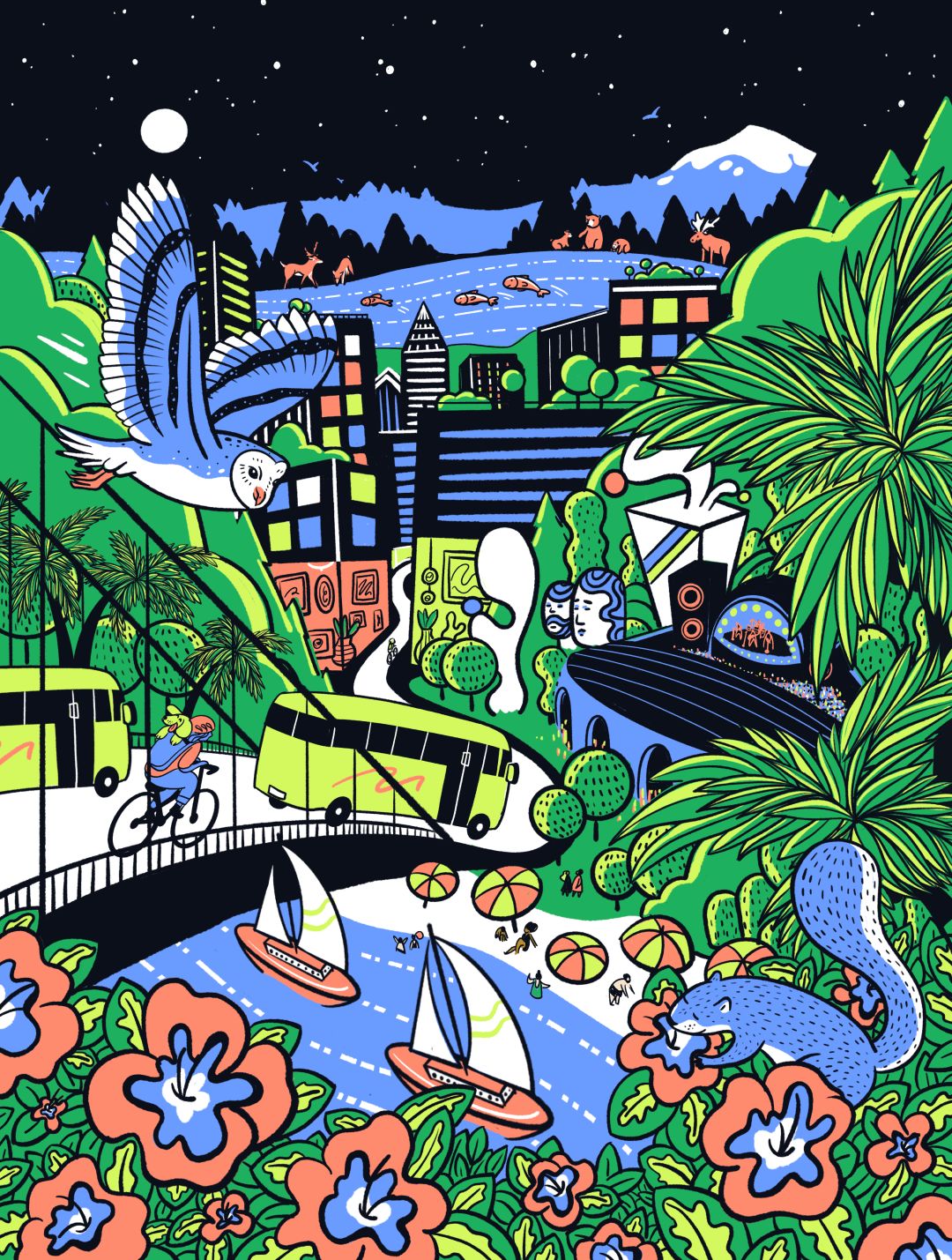

Image: tara jacoby

At 7:45 a.m. on a crisp fall morning, the leather-padded seats of the Multnomah Whiskey Library fill with 50 Portlanders. Philanthropist Dorie Vollum (from the namesake family of the Vollum College Center at Reed and the Vollum Library at the Portland Japanese Garden) chats with real estate developer Kevin Cavenaugh (the Zipper, the Fair-Haired Dumbbell). Nearby, the respective entrepreneurs behind the Society Hotel and Frances May boutique, mayor Ted Wheeler’s director of economic development, and the policy head for the Bureau of Transportation nibble on pastries donated by the Heathman and New Seasons. All eyes are on the speaker.

This story is part of our 20th Anniversary special feature. Read more about The Portland Personality, What 10 People Really Think About Portland, the Biggest Ideas to Change the City We Love, and our 15-year analysis of whether Portland Has Lost Its Vibe?

“I want commitment,” booms Randy Miller, whose civic development résumé in town goes back 55 years, including chairing the Portland Business Alliance and cofounding Greater Portland Inc. “Everyone comes to the first meeting.” Clearly, Miller has longer-term expectations.

This gathering is for Reimagine Portland, Miller’s call-to-arms to build “the best version of the city that’s ever been,” by convening movers and shakers with policy folks. In keeping with Portland reserve, no one present suggests that the room holds the city’s brightest minds or biggest wallets, but rather, as one attendee puts it, the “social fascia of the city.”

Just 14 hours earlier, many of the same people appeared at a similar event in Wieden & Kennedy’s offices six blocks away, for the ad agency’s launch of Portland Is What We Make It, a campaign to reverse the city’s downward marketing spiral. And many attendees sit on committees of the governor’s Portland Central City Task Force, a quick-moving group charged with “articulating a compelling vision and near-term, achievable strategies to revitalize the economic future” by the end of the year. Among Portland’s creative elite, hunger for change is in the air, as if they’ve just awoken from a dreary three years of pandemic plus urban crisis and decided that they can, in fact, fix everything.

Miller divides the room into groups, and attendees discuss a city on the precipice of becoming a major metropolis, but a wee bit stuck. Pam Baker-Miller, the owner of Frances May, recounts how she needed to buy safety grates, a standard business security item in most cities. Yet she couldn’t find a manufacturer in Portland and had to order from Chicago, one of many signs of a big city stuck in small-town mode.

Next to her, a Portland State University professor of urban studies nods and animatedly describes Portland as fumbling its opportunity to have an international presence: people around the world are interested in Portland, and the city needs to embrace that and present itself as such. “Yes!” exclaims Baker-Miller. “It’s OK to acknowledge that we’ve become a city.” As for how, well, that’s why they’re all there.

If anyone is well suited to champion Reimagine Portland and its mission, it’s Randy Miller. “I was part of the 1970s cohort where urban planners and policy workers, plus a bunch of us in the private sector, joined up to really move the needle,” says Miller, who was named to the Portland Development Commission as a 29-year-old. He rattles off their coups: in 1974, the removal of Harbor Drive, a six-lane on-ramp to I-5 that is now mostly Gov. Tom McCall Waterfront Park, and the cancellation of the Mount Hood Freeway, which would have cut through Southeast Portland neighborhoods and demolished some 1,500 homes; MAX light rail, for which planning started in 1973; and Pioneer Courthouse Square, completed in 1984 and funded in part by sales of 50,000 bricks at $15 each (the funders’ names are stamped on the masonry).

“We established the fundamentals of why Portland became so prosperous and popular, and very attractive to highly educated younger people,” says Miller. He means environmental stewardship, pedestrian and cyclist infrastructure, and civic engagement. Unlike other cities, where top-down power shaped the landscape—think Robert Moses, whose New York City highways were implanted by sheer force of will—Portland formed around people, not patrons. “All the elements that made us great are still here.”

Miller’s optimism is not misplaced. Though foot traffic in Portland’s city center is down 39 percent from 2019, compared to a median of 26 percent among major US cities, according to a June analysis by the University of Toronto, the economic data indicates that Portland can support rejuvenation.

“From a regional perspective, things look pretty good,” says Josh Lehner, senior economist at the Oregon Office of Economic Analysis. “We never minimize the issues in the urban core, but the regional economy is doing just fine.” Compared to the 52 other US metro areas with populations over 1 million, Portland is in the middle of the pack for job growth, and above average for income growth.

Attendees at Reimagine Portland’s first meeting pause to refill their cups with donated Coava coffee as discussion turns to the path forward. A key, unspoken understanding permeates the room: Portland became a widely envied city partially because its residents didn’t care at all about what outsiders thought. They just rolled up their sleeves. Through the ’90s and ’00s, residents grew their gardens and built their curbside library boxes and brewed kombucha. It was a myopically inward-looking city, where pursuits came from the heart, and funding followed sometime later. “Portland used to do stuff that no one else does. Bold, inspiring stuff,” says Reimagining Portland chair and cofounder Mike Thelin, who also co-created and oversaw the Feast international food festival, which ran for a dozen years. “And it all grew out of a sense of abundance that there was enough to go around.” Portlanders had a unique knack for building companies around their passions for sneakers or savory ice cream. But now? “No one really knows what we do anymore.”

The problem, of course, is that Portlanders outside the room don’t necessarily know about Portland’s DIY, just-get-it-done ethos, where disrupters and influential outsiders often lead the way. Today, almost 60 percent of Oregonians come from elsewhere—many from California, Washington, Illinois, New York, and Texas, and are likely accustomed to cultures where supporting local business means writing a check or attending a fundraiser (or both).

No one at this meeting suggests Portland should return to hosting major festivals. “A big event isn’t the right move right now,” says Thelin. “Events like Feast exist because of a great culture with great interconnectedness. But they don’t necessarily create those things.” Festivals emerge when thriving creatives and businesses yearn to come together. Portland’s not there yet. “What we need is a culture where we’re supporting neighborhood businesses. We should be asking ourselves what we can do to increase connections in the civic space and really create opportunities and back cool things happening around the city.”