The Time-Based Art Festival Is 21. How’s It Looking?

No matter how you slice it, the Time-Based Art Festival is a feat of endurance. For most of its 21 years, the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art’s annual extravaganza has unfolded across 10 days—a dizzying, sleepless spree of genre-bending art and performance. A flood of creative feats that sweep up and swirl together Portland’s art community, agitating and serenading them like a Maytag before releasing them back to whatever is they do for the rest of the year. Whether Vaginal Davis’s “terrorist drag,” Morgan Bassichis’s cabaret group therapy, or that time Narcissister lit a sparkler after tucking it into her tuck—everyone who’s been has a favorite TBA story.

When we learned that this year’s fest would cluster its events across three September weekends, we wondered: Did this mean time to rest, letting the art infuse rather than consume our days? Or would something be lost when shows didn’t blur and collide in the same way? Delirium, after all, can be fruitful.

Turns out: both. This year’s festival offered welcome breathing room even while making us long, at least a little, for the frenzy of yore. But what hasn’t changed, thank goodness, is the serving up of unpredictable, absorbing work. While we didn’t make it to everything, here are the shows that stood out as we sat down to reflect.

Morgan Bassichis, Can I Be Frank?

Matthew Trueherz: Morgan Bassichis’s show was the first that really affected us both. Bassichis is a New York–based artist and activist who kind of toes the line between comedian and performer. They found a creative ancestor in Frank Maya, a similarly comedy-focused performance artist who worked in the ’80s and ’90s in New York. Maya was dubbed the first publicly gay comedian to be on TV and wound up rather gracefully answering a lot of questions about what it “means” to be gay. Bassichis found a specific Frank Maya show they wanted to, in a sense, recreate: a stand-up set called Frank Maya Talks from 1989.

Rebecca Jacobson: I was excited for this because I’d seen Morgan—I don’t know why I feel like we’re on a first-name basis; they’re a very charismatic, charming performer—at TBA in 2017. I have to say that the Frank Maya of it all drew me less than Morgan’s stage presence and their engaging of the audience.

MT: They had this fake audience Q&A bit where they handed out cards with pre-written questions. The question on mine was prefaced with, “Hey Morgan, I think I saw you in the Portland airport bathroom, didn’t I?” And, of course, before answering my scripted question, they said, “No, I don’t think that was me.”

RJ: There was one that opened with something like, “I have a friend who would like to go on a date with you.”

Image: Courtesy Bronwen Sharp/PICA

MT: I do think this kind of art is very much about, can you as a performer bond with everybody in the room? More than any of the material, it requires that ineffable, enchanting quality. And I think that’s for sure there.

RJ: Often through manic humor.

MT: Several jokes landed with Bassichis saying they wanted to have sex with Frank Maya, or that they feel this sexual connection in the cosmos. They also said at one point, “I want to have sex with all of you!”

RJ: I was struck by how they packed together both humor and rage.

MT: They talked about loving how, during the height of the AIDS crisis, Maya was telling jokes about frustrating dates. People in the audience, and their friends and loved ones, as Bassichis pointed out, were likely in their last few months, and Maya’s still telling jokes about, like, this guy who won’t stay up dancing all night. Bassichis is arguing for maintaining day-to-day life even in a crisis, saying that you have to do both.

RJ: The coexistence of humor and rage as a commitment to being alive.

MT: It makes me think about social media. There’s so much public shaming: How dare you post this personal thing when this war is happening? And, well, you have to.

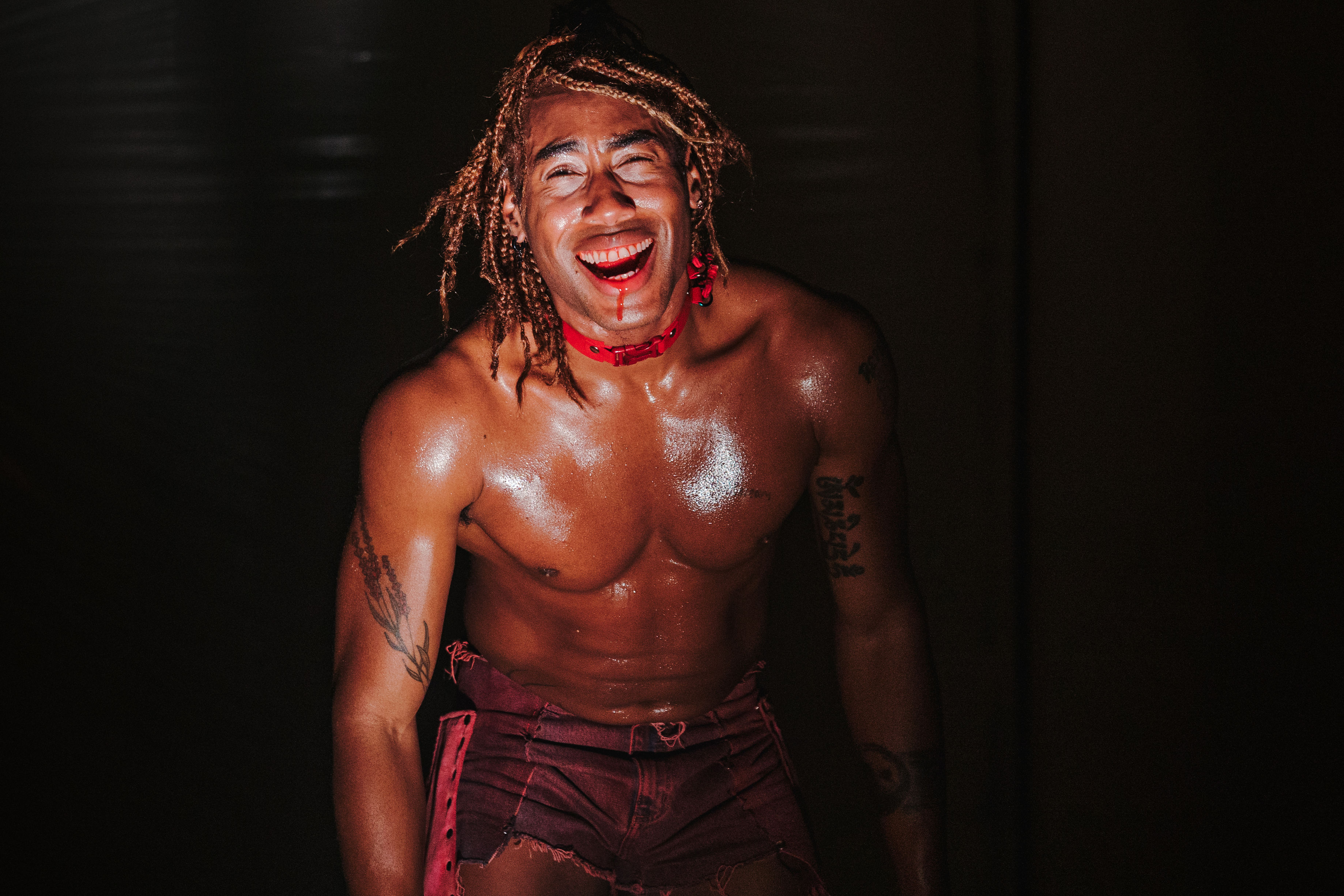

Marikiscrycrycry (Malik Nashad Sharpe), Goner

MT: Speaking of holding it all, we didn’t really know what to expect going into Goner.

RJ: For all the ways TBA has morphed over the years, they have maintained the thrill of forcing you to expect the unexpected.

MT: Goner is a solo show by London-based choreographer and dancer Malik Nashad Sharpe, who performs as Marikiscrycrycry. I guess we had some idea going in. The press release said, “There will be blood.”

RJ: We were informed that, if seated in the front row, we might come into contact with fake blood.

MT: And we knew the show was based around the genre of Black horror, which is about the way Black narratives are compounded with horror tropes. Sharpe is asking, What does that mean for a dance performance? Can you describe the first 15 minutes?

RJ: The first 15, maybe even 20 minutes, all we see of Sharpe is his—

MT: —glistening, toned—

RJ: Let’s talk about his lats and his traps.

MT: You do see his bare ass at one point.

RJ: That comes later. For the first 15 or 20 minutes, Sharpe has his back to the audience, and he’s combining social and contemporary dance styles, including dancehall and other Caribbean styles. It was propulsive, rhythmic, high-energy.

MT: Verging on football practice at some points.

RJ: He’s wearing these reddish-pink jean booty shorts and a sort of bondage-style choker, which looks almost like a long, braided ponytail. He’s leaping into this star jump, arms and legs in an X, getting real lift. And we’re introduced to this movement vocabulary as he’s repeating the steps. I found it entrancing, mesmerizing. But it’s also unsettling because we never see his face.

Image: Courtesy Anne Tetzlaff/PICA

MT: About 15 minutes in, you asked me if we were ever going to see his face. And then all of a sudden there’s the loud noise of a jump-scare in a movie. For a fraction of a second he turns around, sort of jumps, and there’s a flash of light, a millisecond, and in that millisecond he basically throws up blood at the crowd.

RJ: We see this face with this expression of—not exhaustion, but of effort, strain, and then the blood-stained mouth and chin.

MT: We’re left with almost a photograph. He’s gone. But because the theater is totally dark for a moment, we don’t have anything else to fill our thoughts.

RJ: Then he begins moving very slowly from pose to pose behind this plastic sheet. We see his silhouette, but the scale is distorted because of the way it’s lit. So there are times when, maybe as with a bodybuilder, we see the shoulders become really massive, and the waist become tiny. It was walking this fascinating line between…maybe, like, sex and monster.

MT: Again, it was very photographic, this matte, almost-shower-curtain—not unlike the plastic you might wrap a dead body in. It had that crime scene or serial killer aesthetic.

RJ: There’s this exploration of all the ways it’s dangerous or off-limits to be as a Black man: too monstrous, too sexual, too effeminate.

MT: I think the word monster is very fitting—the duality of extraordinary beauty and fascination that a monster can have. A monster is both feared and celebrated, and usually admired from a distance. But this show seemed to kind of close that gap. You like monsters on TV and in books. What happens when they’re spitting blood in your face?

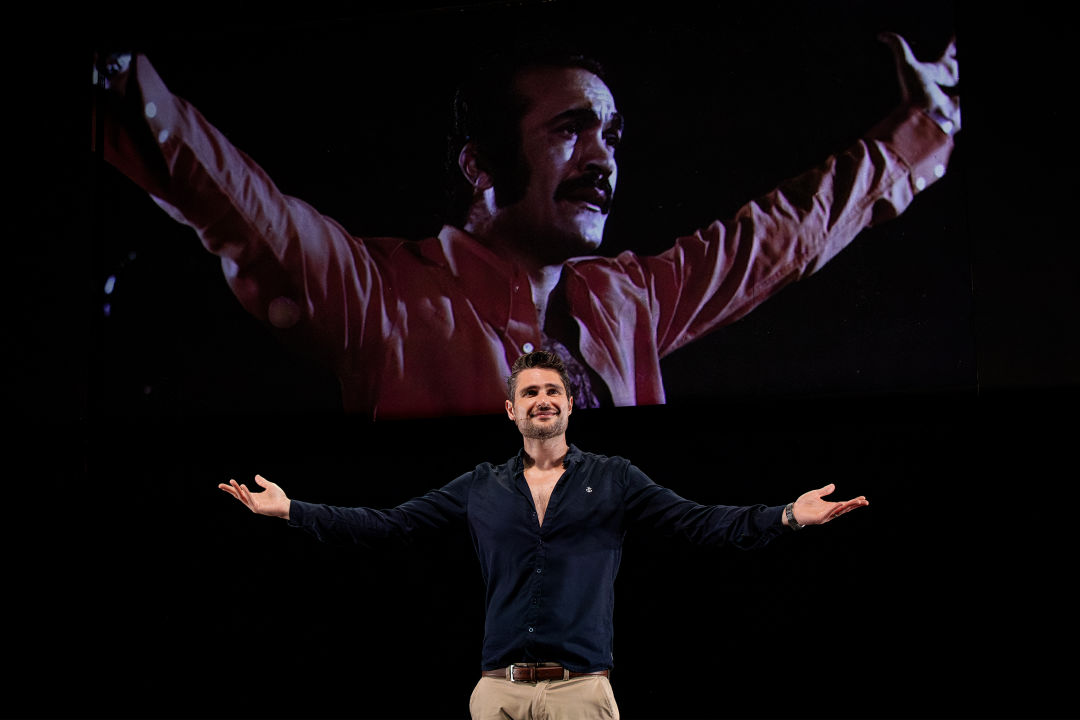

Javaad Alipoor Company, Things Hidden Since the Foundation of the World (produced with Boom Arts)

MT: This was a multimedia play, of sorts, centered around an unsolved murder in the ’90s of this Iranian pop star, Fereydoun Farrokhzad. He was very, very famous but exclusively in Iran.

RJ: From the beginning, there’s a super slick self-awareness. The main performer, almost host, Javaad Alipoor, is naming that he’s in front of an audience, identifying certain narrative tropes he might use to tell the story.

MT: He’s emulating Farrokhzad’s showmanship. He always says the name with gusto, “Fereydoun Farrokhzad,” almost looking up to the sky; there’s a physical thrust when it comes out of his mouth.

RJ: And he starts off by joking about how he is uniquely positioned, being half Iranian and half British, to be this world-bridger. “This show is going to bring harmony and understanding,” you know?

MT: Right. He calls this pop star “the Iranian Tom Jones,” which isn’t really a clear reference, uh, today, especially in America. Like, great, who’s Tom Jones? (“It’s not unusual to be loved by anyone”). But it’s more about the comparison. Saying this guy was like Tom Jones sets up other examples of feeble connections.

RJ: “A pomegranate is like an apple.”

MT: Right. This is how you relate your experience or your culture to people in other cultures. But the point is, there’s no such thing as like. These are two different things.

RJ: There’s also a moment early on when we are all instructed to use Wikipedia, and he says some things about Wikipedia that sound incredibly intelligent but are potentially dubious. He’s extremely eloquent and convincing, but it’s all coming at you so fast that you don’t really have time to absorb it, much less engage with the truth of it. That foreshadows this multimedia barrage that the show becomes.

MT: It’s really about media literacy: how so much of what we think we know hinges on surface-level comparisons; this is like this.

RJ: Another performer, who I think you and I agreed had the most effective presence, plays a podcast host. She really captured the self-serious but winking delivery of a true crime podcast (I say as someone who doesn’t listen to true crime podcasts). She takes you on this ride that at first makes sense but then becomes this mess of information and words. The podcast’s tagline was, “The more you know, the more you understand.” That tension between knowledge and understanding is something the show delights in playing with.

MT: We’re essentially watching a live version of a podcast YouTube clip, where the screen is overlaid with “proof,” or whatever, which is usually like a Wikipedia page.

RJ: We’re scrolling, we’re opening tabs, getting images and little video clips.

MT: It peels apart things that feel very concrete as a person in 2024 looking at the internet. It seduces you. Then once it has you, it shows you that this is all kind of—that nothing is like something else. You don’t actually understand, and you couldn’t possibly by listening to a podcast about it.

RJ: A friend introduced me to the concept of a “perhaps-fact.” And saying, “So I heard on a podcast that…” is the prototypical lead in for a perhaps-fact.

Anthony Hudson/Carla Rossi, Queer Horrors

MT: So—Carla-Rossi-slash-Anthony-Hudson. What would you call them?

RJ: Multihyphenate?

MT: Carla Rossi is a drag performer, a “drag clown.” And out of drag, Anthony Hudson is a film scholar of sorts, and film programmer, and a filmmaker. They brought their Hollywood Theatre series, Queer Horror, to TBA, which was one of several party-slash-performances at the festival.

RJ: Right, with Queer Horror they screen horror movies that engage with queerness and make the argument that horror is a queer genre.

MT: In a tongue-in-cheek but actually quite serious way: Queer horror is not a sub-genre. Horror, as a genre, is queer.

RJ: And this TBA program made the film series over as a party, with short films made by or with Anthony-slash-Carla. We saw some other notable drag performers, including Pepper Pepper, originator of the much-missed Critical Mascara, a past TBA staple. Cut with those films, we got horror-themed drag performances, most of which had their own video elements.

MT: And for context, this is in a very large warehouse. The ceilings are several stories high, wide-open. People are sprawled out on beanbags, and across layers of different benches and what not. There are also people selling things around the edges, like a makers market.

RJ: You could buy, like, cunt earrings.

MT: Yes. You could also get a bumper sticker made of your own childhood photo, books, art prints.

MT: We had something of a Vampira tribute that did have some video backing, which started with a bat-winged cloak situation and ended about as close as you could get to nude.

RJ: We had some spinning of tassels.

MT: Which was a theme for the night.

RJ: Shedding of clothing, you mean?

MT: Yeah. The duo Izohnny, Isaiah Esquire and Johnny Nuriel, was pretty epic. They had these lit-up batons.

RJ: A little bit lightsaber vibes.

MT: They stood very regally at the back and waited for everybody’s eyes to land on them: severe, dramatic, commanding. Then they romped toward the stage in an elegant stop-starting of poses with the…what we’re calling lightsabers.

RJ: Right. And the poses invited audience response. They were also, in the way one does at a drag show, walking around with a bucket of cash.

MT: Effective nonverbal communicators.

RJ: This event came closest to the party energy that I’ve experienced at TBA in the past.

MT: It was certainly asking, When does a performance become a party, and a party become a performance? There’s something interesting about losing track of whether you’re attending a show or hanging out at a party—and it can be both. Usually, when you talk about performance in a fine art context, you don’t necessarily think about getting a drink and talking to a friend during the performance, as you would at a concert. But PICA was clearly interested in blurring those lines—shows you can kind of live in.

RJ: I like that impulse to program work that combines performance and social opportunity.

MT: In my preview of this year’s festival, I wrote the phrase “social performance.” And you were like, “What is a social performance?” I said I didn’t know and reworked the line. But I think we wound up attending a few social performances after all.