15 Years Ago, Portlandia Told Portland Who It Was

Steve Buscemi is celery. Or rather, he represents the vegetable’s interests. A pantheon of ad men responsible for the cultural perceptions of vegetables has gathered in a dramatically lit conference room: heirloom tomatoes (“didn’t even exist five years ago”), kale (“consumption is at an all-time high”), brussels sprouts (“don’t know how you did it, Bill”). Celery’s numbers are down. Though it is Buscemi’s job, changing how the public feels about celery seems ridiculous to him. Like the rest of us, he has a naive faith that trends come from the cosmos, not corporate machinations.

Elsewhere, Steve Buscemi is the letter Q, forever out of place in the alphabet. Why, he laments, must he always be grouped with the normies, when he clearly belongs at the back of the alphabet with the other esoteric letters, X, Y, and Z? Q is a provocative noise musician, with a sloppy blue mohawk and matching soul patch. But he has celery’s fatalism. Q is ahead of his time, and that’s OK. What is he supposed to do, ditch his “little stick” and work as O’s understudy? Ridiculous. Celery once ruled. Its time will come back around. Ever heard of Bloody Marys? Ants on a log?

Image: Courtesy Augusta Quirk/IFC

Buscemi played celery in an extended Portlandia skit. He was Q in Julio Torres’s HBO show Fantasmas, almost a decade later. Though set in Portland and New York, respectively, both shows exist in an absurdist nowhere: the collective imagination. Free of realism’s constraints, like the most unsettlingly profound internet video, the best of their sketches cut with obscene efficiency to the heart of the human condition. Retaining that humanity, they also manage to show how niche figures come off to the larger public—a nifty duality, sympathetic to the person who is celery or Q, yet capable of articulating where their hopes and concerns fall short of reality.

Torres’s show leans into surrealism and never quite touches down in the world we know. When Portlandia premiered on cable channel IFC in 2011, it made use of a quaint West Coast city known for craft beer, NyQuil doughnuts, and cheap rent, if it was yet known for anything. But the show’s Portland was a bizarro Portland. The eerily regal Kyle MacLachlan, a favorite actor of David Lynch, was mayor. (The city’s actual mayor at the time, Sam Adams, played his assistant.) MacLachlan’s politician is also a kind of ad man, who wears nautical blazers and uses an exercise ball as a desk chair. He spends his days architecting the city’s image instead of governing—a theme Portlandia returns to again and again, aesthetics over impact.

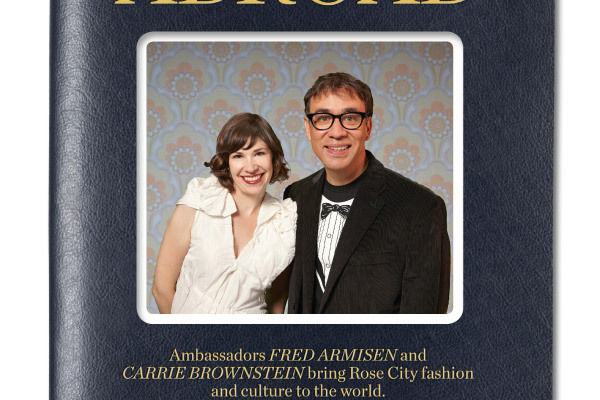

The show’s cocreator and star Carrie Brownstein, a longtime Portland resident, has maintained that its setting was fictional. “It’s Portlandia so that it can be a stand-in for any number of places, any number of ideas or sensibilities,” she told me recently. “Anyone can kind of insert themselves into this landscape.” It’s malleable, but it has a certain texture. As Brownstein’s costar and cocreator Fred Armisen described it in a less quoted moment of the pilot episode’s “Dream of the ’90s” anthem, Portlandia’s Portland is a place where one might still catch something like the Jim Rose Sideshow Circus any odd Tuesday, and “watch someone hang something from their penis.”

Whether it was spoofing or inventing a place, the show’s discovery arc was apt. When an early New York Times review described Portland as the place “where indolence is a virtue, and free time only creates more opportunities for not working,” it didn’t matter that it specified this was “the Portland of the imagination.” The Portland of the imagination was all much of America had. Under this cloud of harmless whimsy, the show quickly became a soundstage for pushing left-leaning ideas of the Obama era as far as they would go. The lighthearted funhouse mirror checked co-op retirees and self-serious baristas alike, reflecting an image that resonated for people who had no connection to the city. And the real Portland could forgive some misbegotten essentializing in service of a larger reality check. Its first season received a Peabody Award for its “good-natured lampooning of hipster culture”—acknowledging that “there is a little bit of Portland in everyone.”

Portlandia premiered 15 years ago on January 21—the day Old Portland died, according to a notorious Willamette Week poll. The refrain is that the show put a cutesy version of the city in front of an audience, and then that audience moved here to get a better seat. 1 + 1 = gentrification, more or less. Never mind that much of the show is a comedy of manners about gentrification, or that the city’s efforts to grow in a way that pushed low-income residents out date to urban renewal efforts of the ’50s and ’60s, which were compounded by racist redlining policies. But Portlanders’ enthusiastic embrace and eventual rejection of the show only bolstered Portlandia’s most salient critique: that the emphasis we place on image, or how we’re perceived, often supersedes the causes we champion or protest.

Image: Courtesy Scott Green/IFC

Portlandia was a popular TV show, relatively, but it thrived as chopped up bits regurgitated online—a sketch show for the modern era. Saturday Night Live creator Lorne Michaels was its executive producer. Armisen had been on SNL for nearly a decade before launching Portlandia. Director Jonathan Krisel had mastered the clever quick edits of the earlier seasons on his previous project, Tim and Eric Awesome Show, Great Job!. And though she wasn’t yet a TV star, Brownstein was a rock star, playing guitar in the Olympia-founded, Portland-based band Sleater-Kinney.

In retrospect, the show’s laughable budget turned out to be its greatest asset. This portrait of a place you kinda sorta know that looks like someone’s dad filmed it on his new camcorder reeked of experimental edge thanks to Armisen’s scrappy industriousness. Brownstein’s earned credibility won over the locals. And the SNL machine cranked in the national hype, hiding in the belly of an indie millennial Trojan horse. Vulture described it as an “IFC underdog” while naming the show the best comedy of the season.

It was a shock and thrill to be known at all, and at first, the city glommed on. “We” were on TV. The Portland Gay Men’s Chorus was the chorus of the “Dream of the ’90s” anthem. The famously reticent artist behind the Portlandia statue even agreed to let her be featured in the intro despite his copyright. Portlandia bike tours cropped up, like a twee version of Sex and the City bus tours.

Brownstein realized how peculiar the embrace was only in retrospect. “I would imagine that for someone that lived in a different city, the idea of having your mayor be in the show, having access to city and federal buildings, would be very conspicuous,” she told me. “But as a Portlander, I have to say it didn’t feel that strange, because it already felt like a city with an eagerness to embrace whatever was in conversation with the city.”

Obama was halfway through his first term. People were earnestly throwing around phrases like “postracial society.” The long tail of the Great Recession was still in play, but instead of doom, optimism seemed to be bubbling below American society for the first time in recent memory. This alternate-reality Portland was a sort of progressive promised land, where so many of the “real problems” were solved that we could focus on the minutiae.

Image: Courtesy Megan Holmes/IFC

Guest-starring in several episodes, Chloë Sevigny helps flesh out this vision of a city stepping on its own toes. Fred and Carrie (Armisen and Brownstein play various versions of characters named Fred and Carrie) first meet her in Seattle, as missionaries for the City of Portland—another program the mayor quasi-sponsors. “Have you considered raising your children under the gospel of Portland?” Sevigny’s character is their only convert, and she winds up living with and dating both Fred and Carrie simultaneously.

Sevigny’s magnetic, effortless charisma translates to the Portlandia universe, and it’s almost enough to excuse her cultural faux pas. She shows up at a café wearing a raven-like wig and splotchy eye makeup, Siouxsie Sioux’s signatures, and says she was inspired by “Sucksy Sucks.” Another day, she wears a striped boatneck shirt not because she loves Godard, but because she liked a sailor outfit she saw in a magazine.

Sevigny—a woman of such ineffable cool that, in 1994, when she was 19, The New Yorker devoted a profile to figuring out exactly what it was she had, and who, decades later, was the cover star of New York magazine’s issue devoted to the “It Girl”—is what Fred and Carrie call a “cultural tease.” They are baffled by her naivety. Funnier is that they’re just one step away from her hollow appropriations. They’re great at stats and facts but know nothing about the roots of goth style or Godard’s critique of American cultural dominance; what’s important to them is pronouncing the made-up name right and knowing that the reference is to Breathless. That is the truth Portlandia finds when it sinks its teeth into a subject—hypocrisy by degree, the pot calling the kettle a different shade of black.

In what’s presented as a kind of elegy (if only), Mark Greif begins a 2010 essay titled “What Was the Hipster?” complaining that the word had been stretching into an all-purpose name to call a certain kind of person, one wholly and ridiculously devoted to trivial matters. Hipsterdom had grown past the hallmarks of PBR and “ironically” reappropriated facets of Americana—“porno” mustaches, trucker hats—into something of a philosophy or worldview. Or perhaps it was what you called someone who, despite their willingness to speak out passionately in public, had neglected to form a coherent worldview.

Several skinny-jeans-and-flannel hipsters show up in Portlandia, but the show is only a critique of hipster culture as it’s understood in this expanded sense. Nearly every Portlandia character seems willing to die for a cause they know next to nothing about. With no direct oppression to contend, the hipster manufactures something to rebel against—say, The Man. But they use that dissent as an excuse for ridiculous behavior ranging innocent and silly (bad jeans, mustache finger tattoos) to oppressive and bigoted (probably best illustrated when Vice cofounder Gavin McInnes, once the molten center of hipsterdom, author of its Bible, went on to start the far-right neofascist group the Proud Boys).

Portlandia mostly stuck to the social aspects of hipster thinking, dressing its characters up in different subcultures as a hobby. Often they are what Greif calls the “rebel consumer”: “the person who, adopting the rhetoric but not the politics of the counterculture, convinces himself that buying the right mass products individualizes him as transgressive.” Locavorism in food feeds the machine particularly well. Insisting on local cheese or getting the name of the chicken you’re eating presents a person as thoroughly “aware,” a warrior against the environmental destruction of industrial farming. But the way the hipster engages in so-called activism is more about themselves than the world around them. They’re not working on legislation or pulling a monkey-wrench gang; they’re picking out brunch spots and pickling everything, eggs to dead birds to used Band-Aids and obsolete CD cases.

Image: Courtesy Augusta Quirk/IFC

This theory may be best illustrated by Spyke, one of Armisen’s recurring characters who is a sort of comic strip version of a bike messenger: flipped-up hat, impressively gross chin beard, grosser gauge earrings. In one skit, Armisen pits him against a normie guy who seems bent on taking over his entire countercultural existence. The dude shows up at Spyke’s go-to bar. The next day Spyke sees him riding a fixie. He even shows up at the studio where Spyke makes art with hot glue and seashells. The square is an omen. Anything he’s doing is totally “over!” The result is a kind of unmasking. Spyke sheds his fixie instantaneously; he even gives up his chin beard when the poser starts wearing one, ruining the way it once advertised his outsider status. Read one way, the sketch could present all of Spyke’s interests as wholly empty pursuits, suggesting that, for instance, shell art has no merit at all. Another take is that this specific person, Spyke, is hipsterdom incarnate, and that his engagement with these pursuits is what’s empty.

In anticipation of Portlandia’s second season, Margaret Talbot wrote a full-length profile of Brownstein for The New Yorker, which traced how she’d gone from punk royalty to sarcastic TV comic. Brownstein had grown tired of the music scene. “The rules are so esoteric, so hard to follow, that no one else could fit in,” she told Talbot. “And what you’ll never admit to yourself is that you don’t want other people to fit in.” Talbot notes, sharply, that the above is the closest thing to a thesis of Portlandia as you’ll get. It’s easy to twist Brownstein’s words into a critique of the post–riot grrrl scene she came out of. But she’s not saying the scene was only about esoteric rules and gatekeeping; she’s saying those attitudes were destroying it. Portlandia and its mode of humor are about chipping off those affectations and reexamining the values they’re supposedly protecting.

Fifteen years later, Brownstein describes her motivations as more personal, nuanced, and sincere. Less than making fun of the city or its people, she describes its guiding questions as, “Why do I do this? Why do my friends do this? Why did my parents act like this around this situation?” These mundane failures are “blind spots,” political and social. “I think we go through life like that,” Brownstein says. “We think that we’ve covered up a blind spot, or we’ve learned, or we’ve progressed, and then you’re just like, ‘Oh!’ It’s like Whack-a-Mole.”

Nobody can sustain the myth of a fully realized person, someone who lives out their every belief. Everybody is a little bit insufferable and has a few holes in their politics—as noted with the Peabody win, everyone has a little bit of Portland in them. Trying to pretend you don’t is the joke of Portlandia. Brownstein’s hope was to find connection in that humility, “to be able to laugh at something and maybe find a kernel of truth.” She and Armisen viewed themselves as insiders making fun of the nuances and intricacies of their own communities. Instead, people saw them as outsiders, mocking those communities in their entirety.

Glad as it was to be talked about, the city quickly became annoyed at being talked about. Bill Oakley, a Portland-based screenwriter known for his work on The Simpsons, was a writer and producer on Portlandia during seasons two and three. As he puts it, “in a very Portland way,” Portlanders “decided that they were no longer as excited.” He stopped telling his neighbors about his job. “I didn’t walk down the street wearing a big Portlandia T-shirt and saying, ‘Hey, I’m writing for Portlandia.’”

Local government and big business never wavered in celebrating the show that gave the city its first taste of real brand recognition. When it ended in 2018, after eight seasons, the City of Portland gave it a ceremonious send-off. Tobias Read, then the Oregon state treasurer, announced that Portlandia had brought $36 million in direct spending to the city, added 200 annual jobs, and put $18 million into Oregon vendors’ pockets. But socially, a vaguely negative connotation lingered then as now.

Easy as it is to dismiss overweighted claims blaming the show for the city’s gentrification, the show did present the country with a very specific “Portlander” trope. To many, Portland is still a place fueled by unrealistic dreams with an undying desire to follow the most progressive cause to the end of the earth. Is it a horrible thing to be known for pickling and reading and caring about food sourcing? No. But as the show went on, and grew increasingly popular, what felt like in-jokes began to land as tone-deaf. The knowing mirror was now a pointed finger.

Image: Courtesy Augusta Quirk/ IFC

The most publicized anti-Portlandia controversy came about when the feminist bookstore In Other Words, known as Women and Women First on Portlandia, ended its relationship with the show. In the recurring bit, both Armisen and Brownstein played extremely obstinate women who run a feminist bookstore. In dramatic fashion, the shop stuck a “Fuck Portlandia” sign on its door and posted a blog with the same title. After hosting the show for six seasons, the bookstore called it trans antagonistic, though its real gripe, like that of most of Portland by that time, seemed to be that the show was annoying and unfunny. That this happened a little over a month before the 2016 presidential election does not feel like a coincidence. It’s funny to poke at the city’s quirks. But as the country began its slow-motion descent into fascism, that good-natured lampooning seemed to apply to every issue important to Portlanders. Everything fell under this same banner of silly and tedious concerns, effectively robbing the city of a meaningful political voice.

Ironically for a show about tiny details, Portlandia’s signature was portraying each character it parodied with as little nuance as possible. The goal was never to accurately represent anyone’s perspective. It was to say, This is what you look like to everyone outside of your immediate niche; this is the result of your passions and activism, however genuine or performative. That’s helpful. People pay for such feedback every day. But its brashness risks flattening, especially when applied to less trivial concerns.

Applying that lens to gender issues, for example, is fraught, minding the show’s wide audience and this country’s lack of a sophisticated understanding of gender, much less different waves and factions of feminism. The idea is not to signal that feminist bookstores are a silly proposition, but that the show’s characters—Candace and Toni—don’t run a righteous or impactful feminist bookstore. They’re lampooning someone who fundamentally misunderstands feminism—conflates sex and gender, reduces people to their genitalia, makes fun of peoples’ appearance—and is overly fixated on signifiers. But mapping this hipster ideology over gender equality, applying the approach that’s funny and sometimes impactful when applied to trivial matters to something of real consequence, reads more like a standard mocking of feminism writ large. You risk equating women’s rights to waiting too long at a four-way stop.

Portlandia’s approachably lo-fi vision of brunchers and bicyclists with only the most eccentric of worries has since been replaced by sensationalizing live streams and mawkish, parachuting reportages, which come from all points on the political spectrum. Whether portrayed as burned-out or annoyingly idiosyncratic, the city’s spirited protest culture dates back nearly to its founding in the mid-nineteenth century. Its reputation as the impressionable place that’s all too eager to follow quixotic ideas to its own ruin could be pinned to a certain IFC television show. But reports from “Little Beirut” in 1991 tell a different story. And when Trump, in his second term, announced plans to deploy troops to Portland to “restore law and order,” he leaned on an image of Portland that portrayed its progressive ideology as not ridiculous, but dangerous. That messaging is, in fact, counter to the portrait of Portland portrayed by Portlandia. It’s almost as if Portlanders maligned the show not for its approach to parody, but for making anyone look in our direction at all.

I was 17 when Portlandia first premiered. Revisiting it for this story felt like stumbling upon a Facebook “wall” frozen on a glitchy 2011 laptop. The contrasting white drawstrings of its many American Apparel hoodies glared like halogen headlights. But as I watched, the show also became a jolt, something to refresh all of this city’s absurdity—beautiful and trying as it is—that I’d become so thoroughly inured to.

Day to day, I noticed things. Why is there a place called Harder Day Coffee Company? Why are one or two of the dozens of flower bins at New Seasons labeled as organic? I noticed things in myself, too. On a podcast I was listening to, someone mentioned they’d recently gotten food poisoning while visiting Portland, and suspected it was oysters, which were topped with cotton candy ice cream. I guffawed, mildly annoyed. As I said out loud that it was clearly a granita, I understood that I lived in a gentle land of make-believe.

In season three, there is a Portland Monthly skit in which Brownstein essentially has my job. She writes a story about a guy who exemplifies the apex of 2010s masculinity: a man who left his office job to make furniture. But another sketch from that season pulled me more thoroughly into the show’s zany vacuum. It begins like many Portlandia skits. Fred and Carrie are supposed to meet up but get caught in a frenzy of the city’s eccentricity.

Art is the problem this time. Carrie is at a gallery, and a woman she tries to talk to tells her that she is her artwork. It’s titled Onlooker. A traffic cop giving Fred aggressively conflicting directions turns out to be a performance artist. Someone steals Carrie’s purse. (“What is personal property? You know, How do we see ‘theft?’”) “Art project” is the ultimate alibi, and the whole city seems keen to employ the trump card of artistic license, whether accidentally or maliciously.

After getting robbed, Carrie tells her mom that the guy said it was just an art project. “Well, I can understand that,” her mom says, sincerely, and tells Carrie about an art project she and her father once collaborated on, pointing to a museum-like placard on the wall: “Carrie / Mixed media: vagina, penis.”

Finally, Fred and Carrie unite, as they have so many times before. They pick up a suspiciously cliché Portland conversation, their tone saying they’re both in on the joke but unsure of where it ends. Carrie suggests they go to Stumptown. Fred says Jackpot Records after. And as Carrie mentions Screen Door—“That’s on Burnside, right?” Fred enunciates in an awkwardly canned voice—the shot zooms out to reveal that they’re incepted into a larger artwork, a wonky miniature of the city, at what looks like a student art show. On the wall, a label reads: “City of Portland / Dirt, water, buildings, rocks, cars, bicycles, citizens, tourists, animals, glass, mixed media. / Started by conceptual artists Asa Lovejoy and Francis W. Pettygrove, 1851.”

It was a self-aware moment for the show. A self-portrait that said, “We’re in on the joke,” reasserting Brownstein’s claims that the project was always a way of checking themselves. Turning the flattening Portlandia lens on itself, the skit acknowledged local critiques about the ways the show often flattened the city. But it also exposed the gulf between what the show was trying to do and the way some received it. Still, I imagine Armisen and Brownstein saw something of themselves in this schlocky self-parody. I did.