Loving Ezra

MY FIRST SON EZRA, was born two weeks late, after four days of backbreaking labor. I had him in 2003 at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) under the influence of Pitocin and an epidural, neither of which was part of the plan. I had been scheduled for a natural water birth. I had taken a Birthing from Within class. I had hired a doula. But, in the end, none of this brought my son into the world the way I expected. And so it was that, in his first moments of life, Ezra began to loosen my grasp on everything I thought I knew.

He was a difficult newborn—crying, never sleeping more than a couple of hours at a time, nursing constantly. I waited eagerly for every development, like all new mothers do, and everything came when the doctors said it should, though just on the late side of normal. Everything, that is, but talking. At eighteen months, Ezra remained silent.

At two, Ezra recognized all the letters of the alphabet. And without using words, he showed us that he understood numbers—in our yard he counted three dandelions with three stomps of his feet. He engaged with the world, just in his own way.

But he still wasn’t talking. Although this concerned me, the worries of others concerned me even more. I took him to OHSU for testing, and evaluators came back with words such as “lowest,” “below,” “behind,” and, finally, “Pervasive Developmental Disorder, Not Otherwise Specified,” or PDD-NOS–a term for the autistic spectrum.

My only knowledge of autism came from a video I’d seen during my student days in a counseling program at Pacific University. The images were devastating: an animal-like child who screeched and banged his head. And now here was my son, diagnosed with PDD-NOS. I couldn’t make sense of it.

In the days that followed Ezra’s diagnosis, my husband, Michael, and I viewed everything through the hazy lens of this new life as a special-needs family. We grasped for solutions. Should we stay home with Ezra? Move to the suburbs? To a deserted island? Although we had bought and lovingly restored a house in the Concordia neighborhood, we decided to move back East. Both Michael and I were from there (from opposite sides of the Hudson River: Long Island and New Jersey), but in some ways the idea of returning felt less like a homecoming and more like an attempt to escape our crisis.

After Michael found a new job, as an urban planner, we sold our house in just a week, then moved, hoping that if the outside world looked more familiar, our new thoughts and feelings about Ezra would become familiar, too.

{page break}

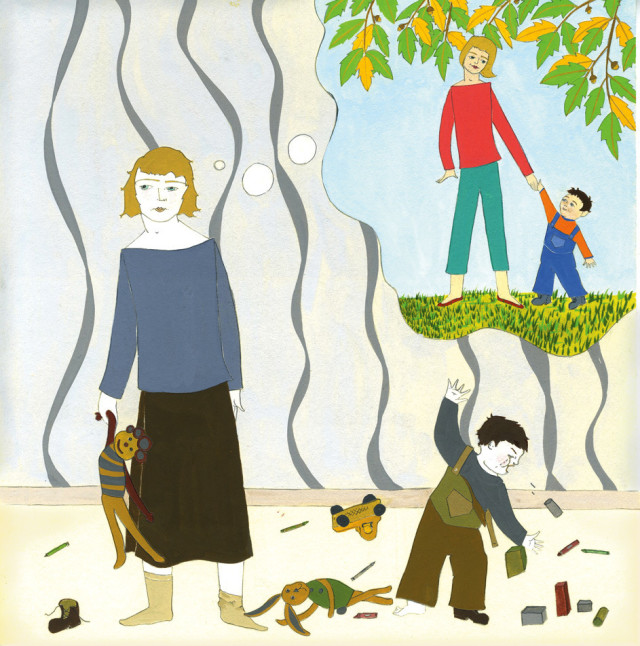

We did our best to adapt to our new surroundings in the Berkshires, a scenic resort area in western Massachusetts. It was hard not to appreciate the long meadows and swaying deciduous trees. As a teenager, I’d spent vacations here with my snowbird grandparents and imagined raising a family in this place: sitting with my young child in a café, or holding hands as we strolled down the sidewalk. I couldn’t have known that life would bring this child instead—this child I compared constantly to my fantasy child, the nonautistic one, even though I knew I shouldn’t.

Ezra turned three that summer, which meant that if we wanted to keep him in speech and occupational therapy we had to put him in preschool. Three seemed young for him to start school. He was talking, but words didn’t come easily. He still couldn’t answer questions, even those that required only a basic yes or no. In the weeks before his first day of class, I lay in bed imagining him in a sea of talking children, all attended to, as he sat there alone, ignored.

When that day came, I packed the only two foods Ezra would eat (Smart Puffs and Earth’s Best cookies); I poured the only thing he would drink (milk) into the only type of cup he would use (a sippy), tucking all of these neatly into his new Thomas the Tank Engine backpack.

Holding his hand, I walked him into the classroom. Other children were kissing their mothers goodbye and walking across the polished linoleum floor to the neatly labeled toy bins and tables. The teacher had already explained her rule that parents must leave.

Even when their children have special needs? I had asked.

Yes, the teacher had said. Even then.

So I walked away, leaving my small, uncertain boy with a ball of Play-Doh.

For the next three hours, I wandered the sidewalks of town, holding Ezra’s baby brother, Griffin, tightly to my chest. I pictured Ezra confused and crying as the teachers forced him to sit on a mat during Circle Time—unable to understand the purpose of this strange ritual.

I returned a half hour before the scheduled pickup time to find the children outside on the playground. The other kids were running and sliding. My son walked alone along the perimeter. When I approached, I saw that his face was puffy from crying. Later the teacher said merely, “He had a rough first day.”

For two months, we continued like this, attempting to inhabit our individual alien spaces—he at school, me in my home office or in grocery stores filled with strangers. Finally we took him out of the school. We tried a Waldorf program, then Montessori, but with the same results. In every classroom, Ezra did the wrong things, or did them the wrong way. It seemed the world could not accommodate him.

{page break}

By then it was winter, the streets lined with plowed mounds of snow. While Michael was at work, I often drove around with my children with no destination in mind: the baby asleep, Ezra observing the falling flakes from his car seat, and me stricken with anxieties he couldn’t even begin to understand.

Michael was drifting, too. Evenings we stared at one another, wordless, like our son so often was. What were we doing here?

An Oregon friend e-mailed in late winter to tell me about a new school in North Portland meant specifically for autistic children, where students were free to learn in their own way. On the School of Autism’s website I found photos of children playing in a tub of beans, finger painting, dancing. I took a deep breath. I didn’t want to have too many expectations—we were so used to disappointment. We had reached as far as Massachusetts to try to feel normal, but was it possible that Ezra’s best home was in Portland after all?

When summer came, we loaded up and drove back West. In the final few hours of the trip, we stopped at a campground in the Columbia River Gorge. Ezra and Griffin, by now eighteen months old, crouched together to investigate the purple petals of a nightshade flower. “See dat? See dat, Ezra? Flower!” said Griffin. But Ezra, a month shy of four, just observed silently.

The campground was quiet except for the distant whir of traffic on I-84. I closed my eyes and inhaled the familiar scent of wet Douglas fir. A decade earlier, I had finished my MFA at the University of Oregon and camped solo in these woods, determined in that angst-ridden, twentysomething way to discover who I was. Funny, I now thought, that anything before motherhood had ever seemed difficult.

I had spent the last few years worried that my family wasn’t normal, but now, watching my boys marvel at a simple Oregon wildflower, I realized that whatever had happened thus far—and whatever lay ahead—was my family’s version of normal.

Later in the summer, Ezra started at the new school. On his first day, he moved hesitantly through the room; he expected to be reprimanded, but he never was. One day, I went to pick him up and found him laughing with another boy. They were yelling out to each other the words on a computer screen and then collapsing in giggles on the floor. No school is perfect, of course, but this one turned out to be a place where Ezra could, as promised, learn in his own way.

As he moved through his year in yet another new place, I learned to love walking hand in hand with him through the city, taking him into cafés. And as I let go of who I thought we were supposed to be, Ezra and me, that fantasy child who once haunted me began to fade away.