Oh, Grow Up

"YOU’RE THROWING your future away!” my grandfather hollered through the phone. It was May of 1995. I was 18 and about to graduate from South Eugene High School, but instead of going straight to college, I had decided to backpack around the world with a friend.

No one in my family seemed to think this was a good idea—least of all my dad, who had grown up dirt-poor in Brooklyn but graduated from Yale with a master’s in engineering. To appease him and everyone else, I applied to the Robert D. Clark Honors College at the University of Oregon and was accepted. Then I deferred admission. Doing everything I had to do to get into college had burned me out on the notion of actually going. So I spent a year immersed in another kind of learning: working on organic farms in New Zealand, participating in a Buddhist wedding in Malaysia, standing open-mouthed in front of Michelangelo’s David in Florence.

By the time I began classes in 1996, I was really ready to commit to my education. To me, college was a privilege. The majority of my fellow frosh, on the other hand, seemed to see it as an opportunity to swill bad beer. Some popped Adderall like Altoids just to make it through the day. I started to think that most of these kids might not be cut out for higher ed.

I’m not saying they’d be better off without a college degree; you need one to make a decent living. According to the US Census Bureau, the annual median earnings for a man with only a high school diploma is $32,435; a bachelor’s earns him $57,397. But statistics do suggest that many people aren’t prepared for college at 18. Consider, for example, that only 53 percent of freshmen entering a four-year program will have graduated after five years, and one quarter won’t return for their second year, according to American College Testing, a nonprofit education research organization. Clearly, there’s a problem.

“Honors courses, standardized tests, and practice application essays … We have figured out how to help kids get accepted to college, but we fall short in helping them cultivate the skills needed to prosper there,” writes Jill Flury in the September 2007 issue of Edutopia, a magazine put out by the George Lucas Education Foundation.

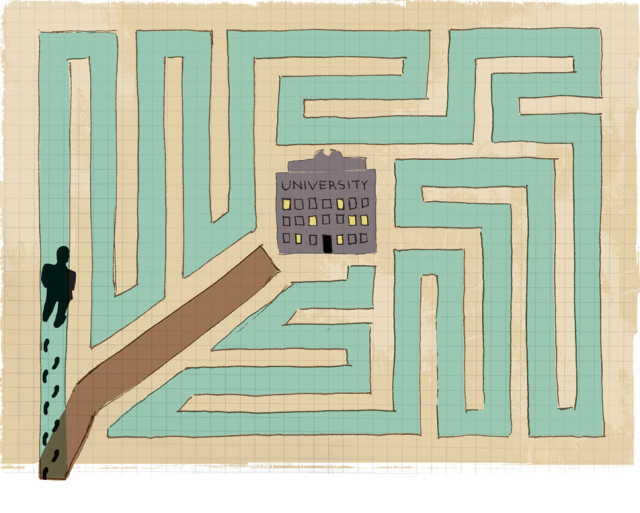

David Conley, director of the Center for Educational Policy Research at the University of Oregon, agrees, noting that colleges require students to be independent, self-reliant learners. High schools, however, tend to be heavily structured places where students are treated more like kids than adults. “Students in high school rarely encounter the kinds of problems or assignments for which the answer is not readily apparent,” he says. “They don’t learn to be persistent with tasks that are inherently difficult or challenging; they’re lost if they have to do more than repeat what they are told.” As a result, many students find college confusing and frustrating at first.

This lack of academic maturity, combined with the increasing pressure to obtain a degree, can place serious strain on a student’s emotional state. And it might well be why college students have more complex problems today than they did over a decade ago, including depression and thoughts of suicide, according to the American Psychological Association. In fact, a 13-year study involving 13,257 students who visited the counseling center at Kansas State University found a dramatic increase in mental health issues—and academic problems were among the top causes of such stress.

{page break}

But amid these issues and the ever-rising cost of higher education (college grads leave school owing an average of $19,237 in student loans, according to the 2003-2004 National Postsecondary Student Aid Study), more and more kids are matriculating. Oregon schools are reporting record numbers for the 2008-2009 school year: For instance, Portland State University predicts fall enrollment to hit 27,000, up from 24,193 just five years ago. The University of Oregon had to find off-campus housing for 400 freshmen this fall because there wasn’t enough room in the dorms. With more students going to college, it’s becoming more competitive to gain admission: Students need higher test scores, better grades, and more extracurricular activities than they did 10 years ago. At UO, the average grade point average of an incoming freshman went from 3.33 in 1997 to 3.49 in 2007.

Working to keep up with the competition in high school can cause real burnout before a student even starts freshman year, as happened to me. Perhaps we need to give kids a break—literally. Instead of riding the conveyor belt straight to college, they might be better served by taking a year to work, travel, study, volunteer, or even, I would argue, simply grow up a little. It’s a choice that might give teens the chance both to engage with the world and to become accustomed to the relatively unstructured environment they’ll find in college—exactly what Conley suggests freshmen need.

“I’ve only seen good examples of what happens when students take a year off,” says Paul Marthers, dean of admissions at Reed College, where about 10 percent of those admitted opt to defer. “They’re usually more mature and have fewer of the ‘just left home’ issues, like binge drinking.”

Some frosh seemed to see college as a chance to swill bad beer.

Taking a year off, often called taking a gap year, is common in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and the United Kingdom (the British government even recommends it). And it’s slowly catching on in the United States. In its letter of acceptance, Harvard University encourages every student it admits to consider taking a year off. The school’s graduation rate of 98 percent may owe to the fact that many students do so, says William R. Fitzsimmons, Harvard’s dean of admissions. Dartmouth College also supports gap years, and Princeton University is working on a program called the Bridge Year that will allow students to spend a year doing public service abroad before starting school. Though few Oregon colleges actively encourage it, some private schools do allow deferment. About 30 Lewis & Clark College admitted freshmen, for example, do so every year.

Perhaps it’s time that Oregon’s public universities got on board—the University of Oregon considers deferments on a case-by-case basis, generally requiring students to reapply if they want to wait a year to attend. “But kids are so stressed out these days,” says Joe Holliday, assistant vice chancellor for Student Success Initiatives with the Oregon University System. “Our goal is to get more students to go to college, and if a gap year helps us achieve that, then we would ultimately embrace it.”

My father ended up embracing the notion, too, even meeting up with me in Greece. I’m still not sure when he smiled widest: When I strode across the stage in 2000 to collect my degree, summa cum laude, or when we stood on a beach in Santorini, sipping ouzo and watching the sun set over the Aegean Sea.