Powers of Preservation

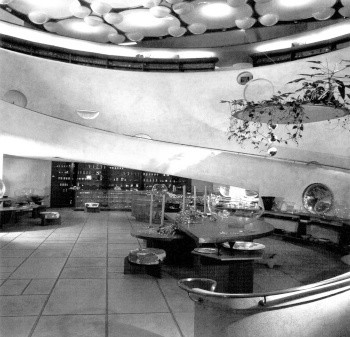

Frank Lloyd Wright's Mercedes-Benz showroom, on Park Avenue in New York City, debuted in 1954, but was abruptly, legally demolished earlier in April 2013. The showroom was one of several Wright projects in which he used a spiral ramp, an "exploration of an architecture expressive of the automobile and its movement through space," in the words of historian David DeLong.

Larry Woodin was in town, and he had a story to tell. He’s a Seattle architect, but he was here because he's also the President of the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy. He whipped through Portland recently to share behind the scenes details of the latest rescue from destruction of one of the houses Frank Lloyd Wright designed.

It was a tale of success, a suspense story and adventure caper all at once: crazy owners, missed plane flights, mysterious anonymous donors, a groundswell of international press, public petitions and 24-hour police protection of the endangered building. The pieces all came together, though, for a happy ending. Woodin and a cast of others were able to save the home Wright designed for his son David, outside Phoenix, in December 2012.

Woodin’s enthusiastic and encouraging talk (which was a benefit for the Gordon House, Wright’s only building in Oregon) had a sad footnote, however. Just that day, in New York City, news got out that an auto showroom designed by Wright in the mid-1950s was demolished. The juxtaposition – the success story of one building being saved, with the sadness of another being wrecked without warning – speaks to some of the never-ending problems of preservation of significant historic architecture.

The Wright design that is no more was a leased space at the corner of Park Avenue and 56th Street that had been a Mercedes-Benz dealership showroom for decades. It was one of only three projects Wright completed in New York City, and was significant mostly for the spiral ramp and turntable on which the imported German luxury cars were displayed. Yes, the Hoffman Auto Showroom, as it was also known, was of a pair with Wright's more famous (and definitely still standing) New York City building, the 1959 Guggenheim Museum: both projects featured spiral ramps.

The Morris Gift Shop in San Francisco is another of Wright's 1950s spiral ramp projects, and is well-preserved at present – in contrast to other Wright spirals like the auto showroom or the David Wright House.

Image: Courtesy Phaidon Press

Wright also employed an interior spiral ramp at his Morris Gift Shop in downtown San Francisco. That building is well-loved and protected at present, as the Xanadu Gallery.

The need for preservation, and the knotty situations that inevitably accompany it, never stop. The Gordon House, while not in danger of demolition at the moment, is still vulnerable not only to the usual ravages of time but also to the extra wear and tear of being open year round to visitors. The non-profit that operates the house is currently mounting a capital campaign for "maintenance projects" – like keeping the cantilevered balconies from buckling (wooden posts are currently propping up a balcony – a detail not in keeping with Mr. Wright's aesthetic).

Visit the Gordon House, in person or online (in this Swansea musical video tour), and find out more. And consider these questions for Portland:

- Which historic Portland buildings are in danger?

- Are there unprotected but significant Portland buildings that you’d like to see landmarked now?