New Photo Book Excerpts: NBA Fashion Decoded, Blazers and All

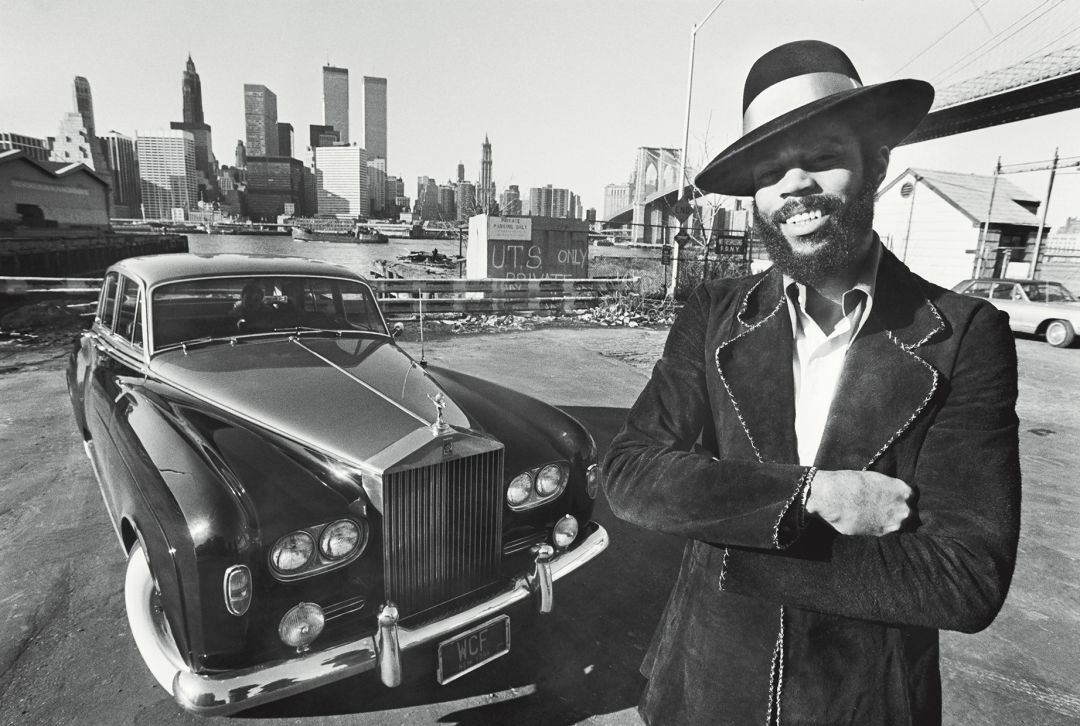

Walt Frazier, a longtime New York Knick, looking dapper

Ed note: Jackson will appear at Powell's City of Books, in conversation with KOIN news anchor Ken Boddie, at 7 p.m. on Wednesday, September 20.

While writing his next novel, Mitchell S. Jackson took on a side project: a coffee-table book covering the evolution of NBA players’ off-court outfits. He soon realized that Fly: The Big Book of Basketball Fashion would be neither quick nor casual. His research discovered a pattern: players’ press conference garb correlated with public affairs.

If Jackson’s name sounds familiar, you may know him as the Portland State University graduate who won a Pulitzer Prize in 2021 for his moving in-memoriam profile of murdered jogger Ahmaud Arbery, published in Runner’s World; he’s also a columnist at Esquire, a Whiting Award–winning novelist, and a lifelong Blazers fan.

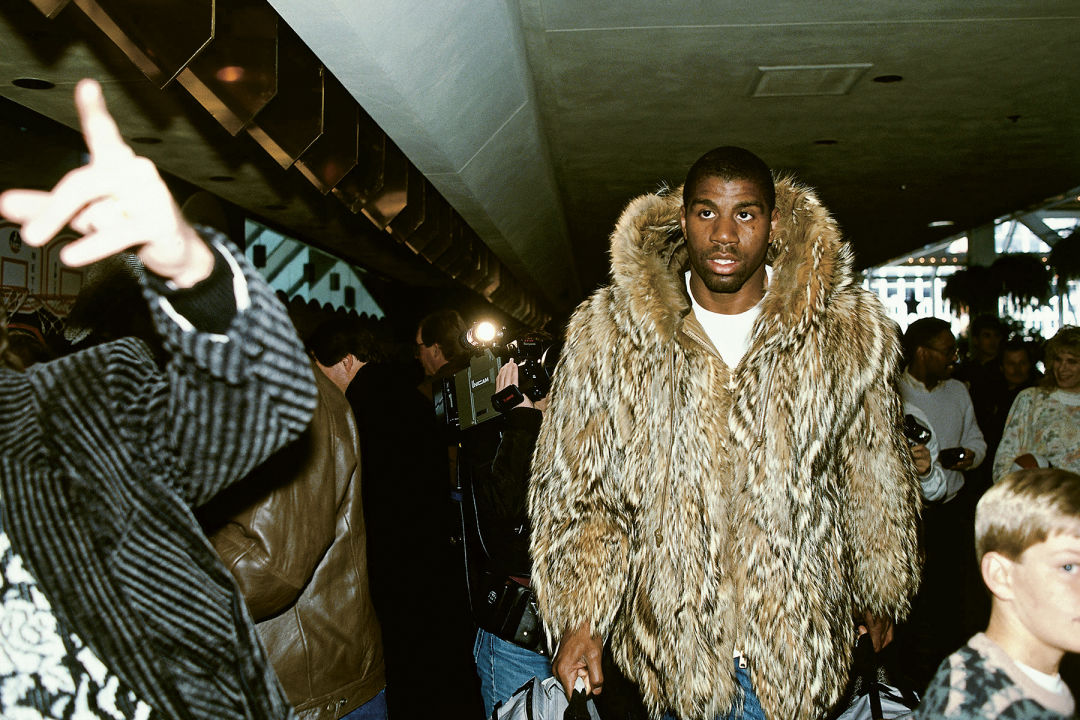

Magic Johnson, one of many top NBA players to opt for fur

Jackson discovered that NBA stars’ fashion was often representative of “where Black people were in their struggle for civil rights,” he said in an interview before the book’s September 5 release. The first Black NBA players took the court in 1950, off-court wearing drab suits to go unnoticed. The Civil Rights Act gave Black players their first taste of sartorial freedom in 1964, the same year the US increased troops in Vietnam. Deadhead styles associated with hippies and antiwar protests ensued. Jackson offers Blazers legend Bill Walton as the moment’s poster child, with his muttonchops, penchant for tie-dye, and signature headbands. (It’s impossible to paint a full picture of NBA style, Jackson explains, without also acknowledging what white players, such as Walton, were wearing.) In an era where Black players had rights on paper, yet came from communities that remained separated from resources, assets, and opportunities, the “fedora cocked just so” and fur-trimmed sport coats of longtime Knick Walt “Clyde” Frazier weren’t gratuitous, but instead asserted his status as a cultural figure. “They were saying, ‘Here’s what’s popular and been done, and we’re not doing it that way,’” says Jackson.

Jermaine O'Neal graced Portland with his looks from 1996–2000, when he played with the Trail Blazers.

Jackson’s prose is lively and bright (“Picture them, envision them”) with argot and enunciated words (Steph Curry’s “f-i-f-t-e-e-n-t-h” three-pointer). He narrates games and “tunnel walks”—through the hallways from the parking lot to the locker room that second as catwalks—with voice that melds fashion critique with love-of-the-game telecasting. Hoops greats of the late ’80s and early ’90s were “deities,” Jackson says. Michael Jordan’s oversize suits and Ferraris were far too lavish for fans to emulate, but devotees could see themselves in early-aughts stars like Allen Iverson and Jermaine O’Neal. “They were our guys,” says Jackson. The aesthetic was the bedazzled nouveau riche also seen in rap: baggy jeans and tall tees, flat-brim hats and limb-size diamond chains. The moment was indelibly tied to the “Jail Blazers,” an era that found players facing drugs and violence charges, and the Detroit “Malice at the Palace” brawl that directly preceded the NBA’s first-ever official dress code. Jackson himself wasn’t immune to the era of drugs and violence: his own teenage drug-dealing years resulted in 16 months in prison, which he recounts in a 2019 memoir, Survival Math, praised for its lucid depiction of the fraught reality of growing up Black in America.

Portland's own Jerami Grant, a forward for the Portland Trail Blazers

The final chapters of Fly bring us to today’s fashion sophisticates, like Blazers forward Jerami Grant, who mingle with fashion designers and become fixtures of the Met Gala and Paris Fashion Week, free to express themselves with clothes. As Jackson sees it, today’s NBA players are able to fully monetize their influence and power, and so rather than dressing for the job they want, they’re dressing to change perceptions of race and even masculinity—and for the jobs they already have, on the court and off.