Author Mitchell S. Jackson Is a Blistering, Lyrical Voice of Our Time

“Others (oh boy this was me) cop a sack from a Big homie, a precooked and acetone-cut underweight dope sack, and stand on a street grown folk warned us off: Failing or Going or Gantenbein or Skidmore or Mallory or Rodney or Church or Roselawn, corners where young boys whose quivering flames were soused previous to ours, carry stolen straps and heavy grudges against the world. . . . That was our universe.”

That was Mitchell S. Jackson circa 1991, growing up in Northeast Portland the son of a crack-addicted mother, as described in his new book.

Then there’s Mitchell S. Jackson in 2015, dominating the stage of the sold-out Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall as he reads from his debut novel Residue Years as Portland’s newly crowned literary darling.

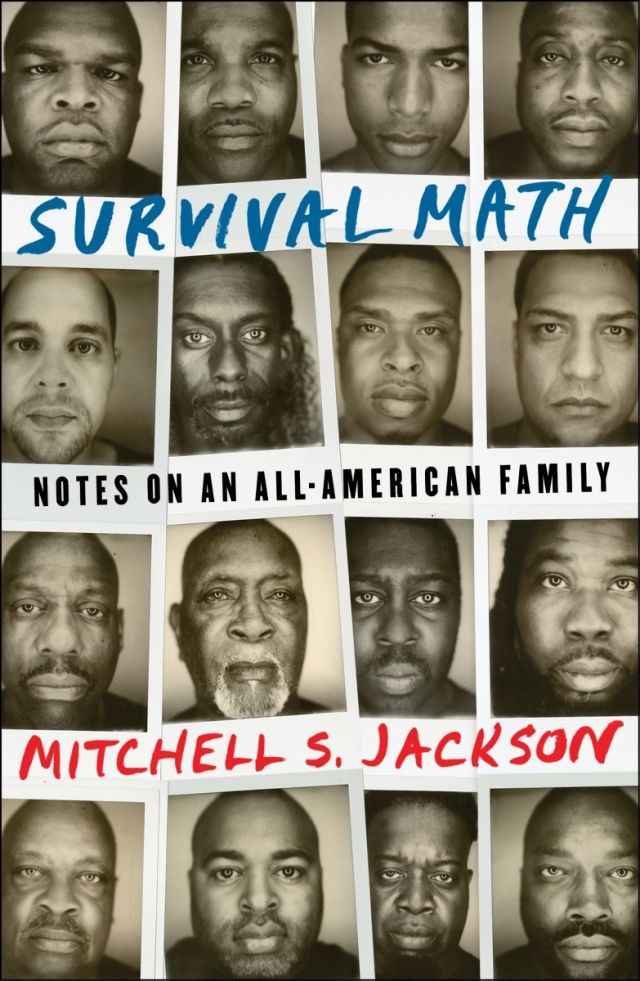

Here is Mitchell S. Jackson now, photographed in the New York Times Style Magazine, as one of its “32 Black Male Writers for Our Time” as he releases his staggeringly smart, genre-busting book Survival Math, excerpts from which will grace the pages of the New Yorker and Harper’s Bazaar this spring.

Jackson’s is a voice that might not readily be associated with the Portland imprinted on the national consciousness—about as far from white hipster clichés as is possible—but it is very much of this real-life town, delivered with a lyrical bent and intellectual rigor that begs to be heard.

Survival Math: Notes on An All-American Family is a series of blistering, lyrical essays that mine Mitchell’s life story as a springboard to explore the social, political, and historical contexts of his own experience—as well as the odds of making it through adulthood as a black man in America.

Image: Courtesy John Ricard

Critics are already raining down plaudits, and they’re right: This book is a vivid and artful exploration of race and legacy in the United States, told in a poetic and piercing voice unlike anything else in the lit world right now. Jackson’s energy fizzes through the pages and takes him swooping through history, narrative, and theoretics. (The footnotes alone are a meticulous and swaggering display of mental dynamism.)

For Mitchell, writing nonfiction was a natural and intentional move: He didn’t just want to tell a good story. “I was reading about the Enlightenment thinkers and how they believed that the clearest evidence of your intellect was writing,” he says. “That’s what I really wanted to do with the [essays]: make them look at my mind.”

It’s a mind that collects and parses information from a blinding array of sources: Baldwin to Nietzsche to the Torah; the origins of apples to criminal profiling to the development of conscience in early childhood, a kind of mental dance that surprised even the author himself. “I didn’t imagine I’d be researching Alcibiades in Ancient Greece,” he says of the Athenian statesman and renowned lady-killer who makes a cameo in the book. “But I kept spinning.”

He also explores his own treatment of women in a forthright essay in which he invites his exes to add their voices to the text. “I learned that I’m a sucka,” says one. “I think you’re broken,” says another.

Interspersed with the essays are “Survivor Files,” stories from Jackson’s male family members, each of whom he photographed and asked the same question: what’s the toughest thing you survived? There are stories about being evicted as a child, spending time on a naval base, a complicated child custody battle, and more. Each of these men, as Jackson points out in the book’s author’s note, is part of the American story. “We are all-American,” he writes. “Which is to say, our stories of survival are inseparable from the ever-fraught history of America.”

Jackson grew up shooting hoops in Irving Park and making money selling drugs until he got caught and sent to Oregon state prison in 1997 at age 21. He spent a total of 16 months behind bars. Today, he’s drinking green tea with a heavy dash of honey at the downtown Powell’s and testifying to a kind of double life: his New York literary existence, and a hometown scene that remains at a far remove from that.

“I didn’t even know what Powell’s was until I was in graduate school,” he points out, nodding to his path from prison to Portland State University and, eventually, New York University, where he now teaches. “This was so far out of my cosmos.”

Home in Portland for a week, he’s reconnecting with those among his friends who are not “dead or doing a long stretch.” He dodged those fates, he says, because he had a line he wouldn’t cross. For example: “I’m going to sell drugs, but I’m not gonna kill anybody.” He pauses. “I considered it. So it wasn’t like it was just completely off-limits, but it was like, ‘Nah, I don’t want to be that.’”

Such choices probably saved his life. But it was an encounter 10 years after leaving prison with legendary editor Gordon Lish (famous for his work with Raymond Carver and Richard Ford) that cemented Jackson’s already fervent literary ambitions. He recalls taking a workshop with Lish, who told him early on he had “an ear.” “He would call me late at night and leave me voice messages like ‘Mitchell, I think you can be great.’”

Image: Courtesy Simon & Schuster

Lish’s mentorship not only fueled Jackson’s self-belief, it pushed his craft to new levels, the evidence of which pulses through the pages of Survival Math. Yet he didn’t just write it for the New York literary elite. “I have imagined coming home and going to find all my homeboys that I hustled with and saying, ‘Here, I wrote this for you,’” he says. “I’d hope it would broaden their perspective.”

Still, he wants the audience to expand beyond his hometown circles. “I also I feel like I’m writing towards an intellectual audience who dismisses these circumstances as things that happen to other people,” he says. “I’m telling them, no, there are these experiences and they’re human, and we don’t want you to feel sorry for us. We don’t want your sympathy.”

He knows there are people who will come to his book to “understand the black experience,” and that’s OK by him. “You can come to the book for that, and I don’t think you will be able to leave with such a reductive sense of what I did.”

What, then, did he do? Mitchell points to his mentor Lish: “I was like, if I can take his aesthetics, his philosophy, and I can marry it to this experience that I had, I have a really good chance of doing something no one’s doing.” And he did.

Mitchell S. Jackson (in conversation with Judge Adrienne Nelson)

7:30 p.m. Mon, Mar 11, Powell's City of Books, FREE