Book Binders

WHILE STICKING price tags on a stack of pawned books at Powell’s on New Year’s Day 2004, my coworker handed me a Webster’s dictionary. “Look,” he said, pointing to blue ink on the title page. “This person didn’t waste any time.” The inscription read: “Merry Christmas 2003!” Daydreaming, I wondered if the owner might not have been given it by his estranged mother, an English teacher who nitpicked her son’s grammar growing up. Only a few days after receiving it, he must have sold the book to ward off bad memories of his childhood torment. My heart went out to him.

On another day, I was cleaning up a few hundred used books to ready them for shelving. From a 1901 edition of Ernest Thompson Seton’s Lives of the Hunted, I erased the words “To Philip, from Mama,” and then felt as though I’d just driven a tractor through a graveyard, knocking over the headstones.

In the six years that I worked at Powell’s, I encountered other evidence of the multiple and sordid lives of books: naked photos, handwritten notes, 30-year-old postcards, flattened joints, receipts from stores that no longer exist. All slipped between pages. All forgotten. Most clerks just threw this stuff away. After all, with each of us acting as a kind of biblio-adoption agent, we were merely expected to facilitate the smooth transition between a book’s former owner and its future one, not to invest the pages with emotion or meaning. Instead I tended toward the sentimental: I stored these artifacts in manila envelopes labeled “Powell’s Found Items,” and I began to see such traces as unrecorded layers of exhausted love.

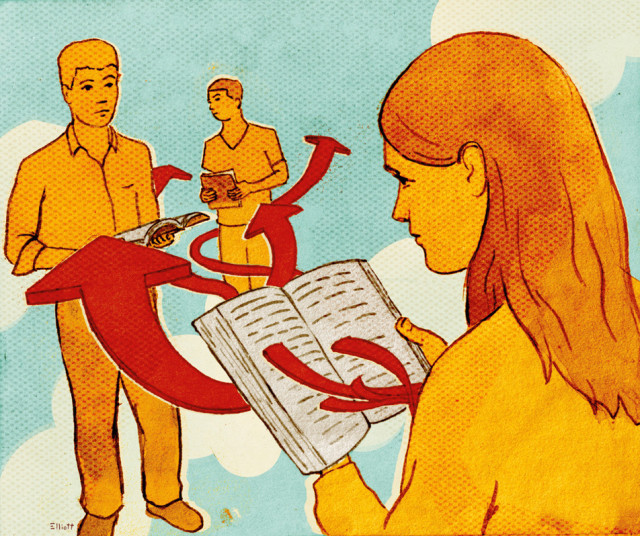

But while all the inscriptions and bookplates and artifacts held in those pages had the potential to expose rifts in past relationships, I also came to see the books that surrounded me each day as catalysts for relationships that had yet to form. People passing each other in the crafts aisle might pause briefly at the same shelf, might be drawn to each other—even moved to speak to each other—by the magnetism of a book like Simple Screenprinting. For me, the stacks at Powell’s became barometers of social, romantic, and intellectual compatibility. It was no Myers-Briggs personality test (and my flimsy synopsis makes it sound like a literary zodiac), but really, if I ask a woman what she’s reading and she says Dr. Phil, is there any hope for us?

I worked in the science section for the majority of my time at Powell’s, so I pined for a certain species of reader to appear—like the gorgeous woman in hiking boots and glasses who once browsed my canids and small-mammals subsections. I asked if she needed help and she blurted, “Cool!” while holding up Lone Pine’s Squirrels of the West guide. “I have to have this,” she said.

“That,” I said, “is the best field guide on western squirrels I’ve yet seen.” Yes, What incredible geeks, you’re thinking, but that’s the core of what I like to call my Barometric Book Theory. Just as any trained biologist or serious outdoorswoman would, she used the word ungulates to describe the elk and deer family and named Pojar’s Plants of the Pacific Northwest Coast as a favorite. And so I pressed further, testing her tolerance. “Do you like bats?”

{page break}

Her russet-colored eyes met mine as she whispered, “I love bats.” I considered proposing marriage right then and there. Or at least suggesting we go bat-watching in the Willamette Valley sometime, Merlin Tuttle’s America’s Neighborhood Bats in hand. Then her boyfriend arrived.

As it turns out, I wasn’t the only person who saw books as potential filters for “love and other difficulties,” as Rainer Maria Rilke referred to such complicated matters of the heart. Some people used the author events I hosted as a place to troll for dates. Of the 50 folks who attended the 2005 reading of Big Bosoms and Square Jaws, the biography of sex-traordinary cinematographer Russ Meyer, the first to arrive was an artificially tan, mid-40s man with slick black hair. He marked his seat with the book, approached me, and, nudging the air with his elbow, said, “Hope some babes show up.” Then he winked. At the reading for Jennifer Leo’s The Thong Also Rises, I watched a man enter a fellow twentysomething’s number into his phone so they could arrange a time for what he promised would be “a night of wine and weirdness.” Was this a Portland thing, I wondered? A citywide behavioral quirk revealing another, more amorous layer to Portland’s bibliophilia?

But really, if I ask a woman what she’s reading and she says, Dr. Phil, is there any hope for us?

Unfortunately, I was never able to provide my own empirical support for the Barometric Book Theory—though I culled plenty of evidence by observing others. Yet there were still other kinds of book bonds besides romance I had yet to discover, ones that age and distance could not break.

One day, a clerk named Adam asked if my last name was Gilbreath. When I said yes, he showed me something scribbled on the covers of three Little Golden books: “Aaron Gilbreath,” each inscription said. “1979.” It was my mother’s unmistakably clean, looping script. My dear mom keeps my childhood artifacts in a chest back in Arizona: baby blankets, stuffed animals, Popsicle-stick art projects. Although I didn’t recall The Little Golden A B C in my infant library, if I owned it, Mom would have stored it in the chest. To this day, the appearance of the three books remains a mystery. My parents’ house has never been robbed, my folks never went on a pawn-it-all drug binge, and they definitely hadn’t entrusted these items to their then-wandering gypsy son. Yet somehow these books traveled from Phoenix to Powell’s as I had.

Minutes later, I carried them to the register, glad to have back what I didn’t know was missing in the first place.

Thankfully, unlike Philip’s mama, my mom wrote in ink.