The Gospel of Paul

On a warm Sunday night at the end of summer, a squadron of cheerful greeters welcomes visitors to Whipple Creek Church’s weekly “Coffeehouse,” where parishioners are invited to hobnob with visiting Christian authors, orators, and musicians.

The congregation, in Vancouver, Washington, usually holds the event out in its lobby—near the little espresso bar, naturally—but on this night the main sanctuary is nearly full, the crowd singing along with the anodyne praise-pop of two guitarists and a djembe player.

Then the pastor jumps up. With his spiky hair and Abercrombie-casual style, he sports evangelicalism’s semiofficial Hip Young Pastor uniform. “How many of you have read a book called The Shack?” he asks. Out of a crowd of about 300, all but a few people raise their hands, but most, in fact, hold copies of The Shack in their laps.

Waiting nearby, the book’s author, Paul Young, looks like any other white guy in his 50s with a gray, receding buzz cut, but when he takes the stage he transforms into part comedian, part inspirational speaker: He talks about his cell phone ringing at embarrassing moments but also about how the family of a deceased 15-year-old boy handed out copies of The Shack at the funeral, with the teenager’s handprint inside. From the start, Young commands reverent attention: nodding heads, ready laughter, an entirely receptive audience.

Lately, his life has been all about audience. He’s had speaking engagements in Canada, Florida, Texas, New Mexico, California, Tennessee, and Brazil; his work has been covered by Today, The 700 Club, the New York Times, Radio Free Europe, and, of course, Christianity Today. Not bad for a man who as recently as February was working three jobs, one of which involved cleaning toilets. A few years before that, he was just another suburbanoid riding the MAX light-rail into downtown from Gresham, 40 minutes each way, scribbling obscure, complicated thoughts on the nature of God and the meaning of faith—the big stuff—on yellow legal pads.

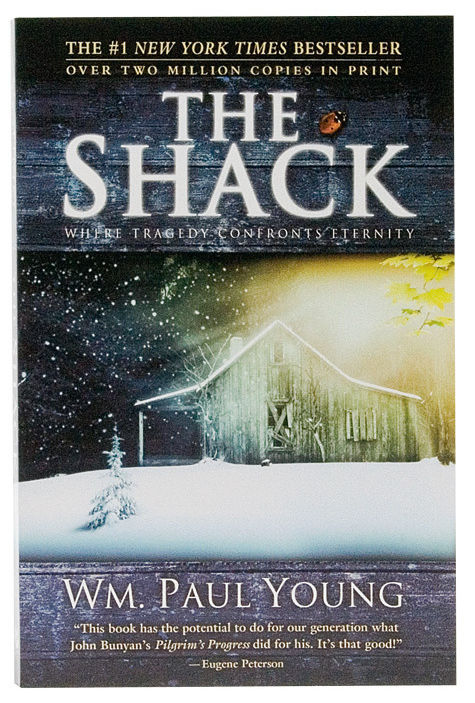

Those commuter jottings turned into The Shack, a slim little novel, basically self-published, that went big. An estimated 3.8 million copies are in print; it’s a New York Times best seller and a top-10 seller on Amazon.com, at Wal-Mart, and, a cultural cosmos away, at Powell’s City of Books. A Brazilian edition in Portuguese just blew through 30,000 copies in a week, and the Spanish translation should hit U.S. shelves before Christmas.

Readers don’t just like Young’s book; they claim it’s rearranging their lives, turning them on to Jesus in a whole new way. In person and in thousands of e-mails, fans tell Young the most amazing things. They say The Shack kept them from committing suicide. They say the book allowed them to deal with childhood sexual abuse for the first time. Dying people want the book read at their funerals. And now, here at Whipple Creek Church is the never-before-published father of six who created the controversial story featuring a serial killer, a mysterious shack in the woods, and the Holy Trinity conjured as a large African American woman, a hot Middle Eastern carpenter, and a sylphlike woman of indeterminate Asian origin. Here was the man, once rejected by just about every publisher in the business, whose book has hit a vein of spiritual yearning no one knew even existed.

“For me, the idea of the shack is a metaphor,” Young tells the people of Whipple Creek. “It’s the place where you store your addictions and secrets—a structure held together with lies. I was in my own shack for 11 years.”

And if that sounds heavy, he hasn’t even gotten to the part about the cannibals.

A few days before his appearance at Whipple Creek, I meet Paul Young at a Starbucks at Gresham Station, a pleasantly sterile complex of big-box retailers near his home.

Young— The Shack’s cover identifies him by his full name, William P. Young, but everyone calls him Paul—stands up from a corner table. Taking my outstretched hand, he pulls me into a big, manly bear hug, which surprises me given that we’ve never met. I later learn that he does that with just about everyone. Young is self-effacing to a degree that might be seen as Zen-like in a less devoutly Christian type. “It’s all just so goofy,” he tells me as he sips at a big, frothy Frappuccino. “It’s God’s cosmic joke, that’s for sure. Seriously, it has nothing to do with me. When I see some of what God is doing with this book, I’m happy just to be a part of it.”

In conversation, Young can veer from down-home humor to philosophical thought to earnest, disarming piety, all within a couple of sentences. This is also a fair approximation of his writing style in The Shack. When Christian publishers first saw Young’s manuscript, about two years ago, they told him it was too weird. Secular publishers found it far too … Jesus-y. Both reactions are completely understandable. Not many mainstream novels feature the personages of the Holy Trinity as major characters. Not many Christian books include epigrams from anarchist philosophers.

Briefly, The Shack goes like this: A young man named Mack runs away from home, poisoning his drunken, abusive father’s liquor on his way out. Decades later, Mack is leading a conventional family life in the suburbs of Portland. During a camping trip in Eastern Oregon, a notorious serial killer kidnaps Mack’s youngest daughter, Missy. When her bloodied dress is found in a remote shack, Mack slides into a long depression he calls the Great Sadness. A few years later, he receives a mysterious note inviting him to the shack. It’s signed “Papa,” Mack’s wife’s nickname for God. Mack goes to the shack and finds God (“Papa”) in the form of a large African American woman with a deft touch in the kitchen, where she’s cooking up a pot of stewed greens. Jesus Christ, the carpenter, is also there, as is the Holy Spirit, the aforementioned sylph.

As one might expect, Mack finds hanging out with the Trinity quite a trip. He suffers a digestive complaint after eating too many of Papa’s greens. He walks across a pond with Jesus. He sees Missy in Heaven. But most of his three-day encounter with the all-powerful threesome is consumed by a long series of complex theological discussions. Mack grapples with free will, suffering, the existence of evil, church hierarchy, the nature of the Triune God, and more. Young crams a major theological problem onto just about every page.

Small wonder no publisher could see the book’s niche. The Shack is part old-time religion, part New Age spiritual healing. It’s profoundly Christian, but sharply critical of organized religion: Young’s Jesus describes religion (and politics and economics) as part of “the man-created trinity of terrors that ravages the earth and deceives those I care about.” The depiction of God as a black woman (some readers have suggested Queen Latifah should play the role in a movie adaptation) strikes many Christians as a fairly radical move. Young tells me, “My mother got to the point where Papa walks through the door and she closed the book, called my sister, and said, ‘Your brother is a heretic.’”

As a group, evangelical Christians are some of the most formidable book-buyers in America. In recent years, they’ve elevated titles like Rick Warren’s The Purpose Driven Life, Joel Osteen’s Your Best Life Now, and the apocalyptic Left Behind thrillers—none soaked in mainstream critical acclaim—to the top of best-seller lists. Warren and Osteen both run slick, franchised mega-ministries; the terrifyingly cheerful Osteen describes himself as a “life coach.” The Left Behind books, with their depictions of end-times chaos, go relatively light on the Gospels’ more touchy-feely dimensions.

Young makes an extremely unlikely addition to that company. His book has a rough, homemade quality—Papa speaks in unconvincing pseudo-slang, for instance—and its overall message is one of capital-L Love. The Shack depicts the Trinity as a free-flowing system of relationships bound by love rather than a formula that can be figured out through the Warren-and-Osteen brand of self-help. Young’s wisecracking Papa and her mystical sidekicks don’t want a culture war; they just want to hang out with Mack.

Perhaps most boldly, The Shack essentially argues that a relationship with God can be found outside the boundaries of formal religion. All of Young’s characters, including the immortal ones, take a skeptical view of organized faith. I ask Young if he goes to church. For the only time during our meeting, I catch a wary glint in his eye. “Do you mean, am I a member of a particular religious institution?” he says. “No. Do I show up in religious institutions all the time? Yes. Usually by invitation. Am I part of a community of people who try to live their faith and discover what love is? Yes. That’s what I consider church. The church is people.”

It’s easy to see why that might give some Christians pause. Even so, The Shack’s most passionate fans can be found in some of the most conservative precincts of American faith, where the book is subject to endless debate on evangelical blogs and is read en masse by congregations. I ask Young why he thinks that is. “A lot of people are just tired of religion,” he says. “Religion can’t heal us. All religions, as institutions, are trying to appease an angry God. People are realizing that an angry God doesn’t work. People are looking for something that calls for some personal authenticity. What I think this book provides for people is a look at conversations between people who care about each other.”

Young deploys a laugh line at Whipple Creek: “Didn’t everyone grow up among cannibals?”

When he was 10 months old, Young’s Canadian parents moved him to remote Papua New Guinea, where they joined a band of missionaries, the Christian and Missionary Alliance, determined to introduce Christianity to several “Stone Age” tribes known collectively as the Dani. At the time the Young family arrived, in the mid-1950s, the tribes practiced spirit worship and internecine warfare. As depicted by the lurid 1962 book Cannibal Valley, by Russell Hitt, Dani tribes often devoured the bodies of slain warriors from rival factions. (Hitt’s book includes a photo of Paul Young’s father baptizing a Dani in a lagoon.)

Young, who lived among the Dani until he was 6, considered himself more a part of the tribe than of his own family. “My parents were so busy doing the missionary thing, they just didn’t have time,” he says. “I was the first white person to become fluent in the language, so when anthropologists came to study the Dani, I was the translator.” He played war games with Dani kids, sculpted with clay, trapped crayfish. He lived the Dani life in just about every respect. “I don’t know that I actually ever witnessed cannibalism, but it happened right around us,” he says. “We were aware of it going on. And the warfare—there were many times that I was right out in it, without being aware at all of the danger I was in. Warriors would chase each other through our house. It never stopped.”

Still, he felt he belonged. “For decades, even after I left, if you asked me to identify my real family, I would say the Dani,” Young says. “I remember being present at conversations about whether or not my parents should be killed. Didn’t bother me at all—I was part of the tribe.”

He also describes Dani culture as “highly sexualized.” Young men would form circles around kids and coax them into performing intimate acts. “It got to the point, when I was 6 years old, I was already setting up sexual situations with Dani girls,” Young says. “And in that culture, the fundamental greetings are all sexual—you say, ‘Can I eat this part of your body or that part?’ Depending on the closeness of the relationship, it can get to, ‘Hi, can I eat your penis?’” At 6, he went to missionary boarding school elsewhere in New Guinea; it was there, he says, that he first realized he wasn’t black, and there that he suffered sexual abuse by the older boys. (One of the most moving anecdotes Young tells onstage involves reunion—and reconciliation—with one of his childhood abusers, a development brought about by The Shack’s success and notoriety.)

When Young was 10, his family moved back to Canada, and his father continued preaching as an itinerant minister. Young says he attended 13 different schools before making it to Portland’s Warner Pacific College, a small Christian school. All along, he says, he questioned the constructs of the Western church. “I think a lot of kids raised outside the culture of their parents have an ability to see the inconsistencies in their parents’ world. For instance, when I came to the West, I thought, ‘Why the repression of women in leadership roles in the church? Why has Scripture been translated and interpreted in this way?’ And those questions take you straight into the nature of God. Is God 51 percent male and 49 percent female, or what? I’ve always been a questioner.”

According to both Young and his wife, Kim, a no-nonsense North Dakotan, for much of his life he came across as more of an answerer. “He always had to be right about everything,” Kim tells me a few days after I meet her husband. “He could argue anyone under the table, and he did. He wasn’t a monster, but that was his identity.”

Young describes this persona as a screen he created to hide the pain of his abusive upbringing and survive in a subculture that prized certainty. “I had a highly developed ability to turn a conversation the way I wanted to go,” he says. “I was really able to defend myself, and to make sure all my secrets and all my shame stayed where no one else could see them. The shack is just my metaphor for that place.”

After college, he worked at East Hill Church in Gresham—not exactly an ideal habitat for an inquiring mind, he says. “There was only so much you could ask about. You could ask certain questions, but not others.” (One upside: He met Kim while he was running discussion groups for college students at a church outside the city. “I walked in,” she recalls, “and he announced that we were going to split into groups of two, and what do you know … ”)

Image: Michael Schmitt

Paul Young might still be the façade guy—arrogant and, in his own mind, living a lie—if he hadn’t cheated on his wife. But he did, and the affair (with one of Kim’s best friends) came to light in 1994. In lieu of strangling her husband (“I hated him for a while,” she says), Kim insisted that he figure out a new way to be himself. “She saved my life,” Young says now. “And she didn’t do it by doing the submissive-Christian-woman thing. She came at me with every ounce of fury she had.”

This marked the beginning of an 11-year spiritual crisis that combined intense soul-searching, reading, and out-of-the-box thinking on life and faith. (It also coincided with a financial meltdown that left him and Kim bankrupt in Boring.) Young’s personal reboot removed him from the mainstream evangelicalism he’d known as a child and propelled him to his own idiosyncratic (to others), authentic (to Young) understanding of what Jesus is all about.

“I had always said that if he ever had an affair, I would leave,” Kim says. “And I would have left—not even having six kids would have kept me in that marriage—if he hadn’t been so truly repentant. I could tell what was going on in him was real. And that’s the only reason I stayed.”

Eventually, she suggested that he write it all down.

All those notes Young scribbled on yellow legal pads eventually added up to hundreds of pages. Before Christmas 2005, he started pulling these stray threads together into a story—a gift for his six children, a sample of Dad’s mind in written form. He executed the first print run of 15 copies at an Office Depot in Gresham, and gave it to family members and a few friends.

A few weeks later he sent a copy to a California author named Wayne Jacobsen, himself something of an evangelical iconoclast whose best-known book is So You Don’t Want to Go to Church Anymore. Jacobsen read Young’s manuscript and found it worthy of more attention.

Young demurred at first. “He said he had no publishing aspirations for it,” Jacobsen recalls. “He wrote it for his kids, and he was done with it.” Jacobsen talked Young into revising the book with him and, eventually, with Brad Cummings—like Jacobsen an ex-pastor turned freelance Christian thinker. For 16 months, the three rewrote The Shack together, to the extent that Jacobsen and Cummings are credited beneath Young on the title page. “We really crawled into the thing,” Cummings says. “At one point, I think we had three different Chapter 11s, and we each thought ours was the best.”

After failing to find a publisher, Young and his partners decided to distribute The Shack themselves. In spring 2007, they printed 10,000 copies and sent out 1,000 to listeners of Jacobsen and Cummings’s podcast, TheGodJourney.com (motto: “an ever-expanding conversation of those thinking outside the box of organized religion”).

“Within 10 days, I’m getting e-mails from all over the world,” Young says. “I get an e-mail with a photo of a roadside memorial in Edmonton, where a father and his 3-year-old daughter were killed by an 18-wheeler when they went out for ice cream. The memorial has a copy of The Shack bungee-corded to it. People are suddenly buying 5 books, 10 books, whole cases of books. And we’re not doing anything—our marketing budget at this point amounts to about $200. Then we’re out of books completely, and with great trepidation, we order another 20,000 copies.”

In news-media terms, The Shack went viral.

Last fall, publishers came crawling back. The book is now being distributed by Hachette Book Group, one of the world’s largest publishing conglomerates. (The Shack trio declines to get into details of the arrangement, except to describe it as a “profit-sharing co-venture” that also involves Jacobsen’s most recent books and future titles they will develop and Hachette will publish.)

Much of the enthusiasm the book is riding owes to the raw emotion of its story: the wrenching loss that Mack—Young’s allegorical stand-in—faces, and that, with God’s help, he is ultimately able to accept. “It gives people an understanding of God that’s lacking in most traditional forums,” says Joanne Petrie, a local hospice chaplain who started giving The Shack to terminal patients before it was widely available in stores. “The people I give the book to in my professional work are searching. I mean, they’re dying. They want to know, is there something of real meaning out there? This book gives them that.”

Yet not everyone is so enraptured.

As Young gets rolling on the stage at Whipple Creek, he feels like there’s something he needs to get straight. “The only road to Father’s embrace is through Jesus,” he says through a fuzz-prone headset mic. “Are we clear? Because there’s a rumor out there that I don’t believe that.”

Not long after the emotional testimonials and laudatory Amazon.com reader reviews started appearing, virulent criticism also surfaced, some of it in easy-to-ignore form: blog screeds that Young’s kids read for amusement, and sniping e-mails Young either deletes or answers with accounts from people who say The Shack changed their lives. But some very loud and influential evangelical voices condemn the book—in language that, to a secular ear, evokes mobs gathering with pitchforks and torches just outside the village.

Chuck Colson, the Watergate felon who became an evangelical icon through his prison-ministry work, accuses Young of holding “a low view of scripture.” From the pulpit of Horizon Christian Fellowship, a San Diego-area megachurch with thousands of members, pastor Bob Botsford condemned The Shack as a spiritual distortion “even more deceptive than yoga.” Mark Driscoll, a pastor at Seattle’s Mars Hill Church (a wildly successful ministry that fuses a punk-rock vibe with archconservative theology) recently devoted an eight-minute YouTube blast to The Shack. In the video, Driscoll, whose sermons circulate widely on the Internet, performs his signature verbal kumite: “If you haven’t [read it], don’t. Christians are going nuts on this book … Christians are freaking out. ‘We love it! This is amazing! Now we understand the Trinity!’ No, you don’t … It’s actually heretical.”

Driscoll then repeats the same indictments leveled by The Shack’s other critics. He accuses Young of creating graven images by depicting God and the Holy Spirit in physical form. He accuses Young of paganism, goddess worship, and modalism, a denial of the Trinity that dates to the chaotic early days of Christianity. For a Christian, this is pretty serious stuff, just the kind of thing the Inquisition took keen interest in back in the day.

That a 246-page novel can inspire this level of passion and outrage says something about evangelicalism’s tolerance for metaphor—or the lack thereof. “Evangelicals, in general, don’t read a lot of Steinbeck,” says Paul Louis Metzger, an evangelical theologian at Portland’s Multnomah Biblical Seminary who writes about both the Trinity and evangelicalism’s relationship with mainstream culture. “We might read Christian romances. We might read C.S. Lewis. But we often have a hard time with metaphor, and I think people are stopping short and looking at this book on the most superficial level. It’s a lack of literary imagination, really. I grieve over the fact that this book seems so edgy to evangelicals, because I think God is actually even edgier than this book.”

The controversy, though, also testifies to an evangelical America in flux. To a secular outsider, evangelicalism may look like a pious monolith. In fact, it is a broad and fractured mosaic. In recent years, an older corps of evangelical leaders—Billy Graham, Jerry Falwell, et al.—began to fade out. A new generation, epitomized by Rick Warren but also including ambitious young strivers like Driscoll, is vying for the spotlight. Energetic upstart evangelicals, awkwardly lumped together as “the emergent church,” are founding congregations across the country; the average “emergent” website is indistinguishable from that of an indie-rock record label. Aesthetics aside, many young evangelicals feel the old ways just don’t work anymore.

“There’s a sense that something profound has ended,” says Michael Spencer, a self-described “post-evangelical” Kentuckian who writes the popular blog InternetMonk.com. “Something profoundly new is coming, and right now we’re in between. Many people feel like evangelicalism as it exists is a failing project,” he says. “I think a lot of evangelicals who read The Shack think, ‘Wow, this is the God I would prefer to believe in, rather than the God of the culture wars.’ They don’t feel like they’ve had a positive portrayal of God put forward for them, and for those people, reading this book gives them a moment where they can say, ‘Aha, there are other people who feel the same way.’”

While some of Young’s harshest critics among the clergy may well have the integrity of their parishioners’ souls at heart, it’s difficult not to think a degree of self-interest is involved as well. “A lot of this is about power and control,” Young says. “Doctrine, and the interpretation of doctrine, has become like property. We don’t live in a feudal system, where you build a wall around your castle. We’ve turned intellectual property—whether it’s your idea of the Trinity or whatever else—into the ground that we wall off and defend.”

The millions of Christians reading The Shack obviously are not fleeing their churches or proclaiming themselves anarchists. In places like Whipple Creek, what seems to matter most is the book’s story of spiritual alienation and renewal—just a reiteration, after all, of the Christian belief that we’re all really, really screwed up but can find salvation in God.

Still, after decades of hearing about a God who wants them to ride into cultural battle against the forces of darkness, evangelicals find a different God in The Shack, one that, not to put it too lightly, mainly wants fellowship. “People are longing for communion,” says Metzger. “The thing they want the most, community, is the hardest thing to create. A lot of times, people see the Trinity as an abstract concept that’s best left alone…. What Young does is take that concept off the shelf and say that it is real, not abstract, and that God is involved in our lives.”

The Shack also constitutes a sort of secular miracle as a testament to American culture’s protean ability to renew itself by sweeping in characters from the fringe. As we drink our Starbucks tea, I can’t help asking Young where he thinks this all will lead. “I don’t see this as a ‘ministry,’” he says. “That kind of language, I don’t really like at all. I have no idea where it’s all going. I don’t want to spend today’s grace on imaginations that don’t exist. The way I see it, my whole life leads up to this conversation at Starbucks, and I’m fine with that. I used to know what God was up to, and I would spend a lot of time telling other people what that was. I don’t do that anymore.”