The Creek

I GO DOWN TO THE CREEK behind my house every Saturday morning. The creek is at the base of the hill, on my side of the neighborhood. The Derbez brothers usually meet me there. They live a few houses down from me on the same side of the street so their backyard turns into the creek too. We consider ourselves lucky to have the creek behind us since most everyone else, when they look out the window, sees nothing but more houses.

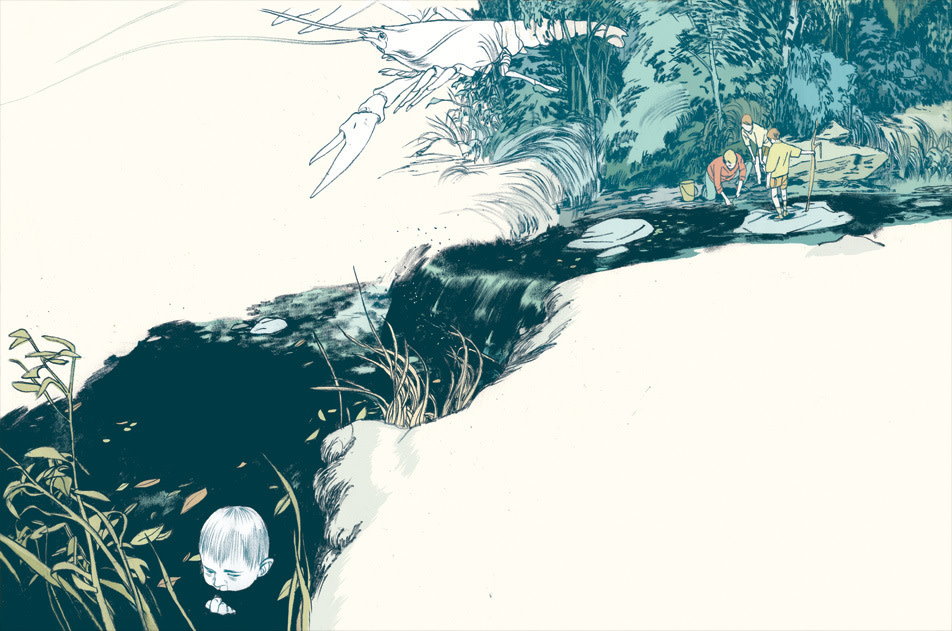

The water in the shallow parts is clear and flows over smooth black rocks, some engraved with fossils of snakes and small fish. In deeper parts, the water is murky and moves faster than it looks. Near the rocky parts, especially where the trees grow into the water and the grass is tall, we fish for crawdads.

We tie leftover scraps of bacon to strings and dip them into the water. The crawdads jump like mad. Their eyes, two little black beads resting atop their heads, swell up to the size of marbles. The brothers aren’t that good at catching them yet but they’re learning. "Just wait for the little suckers to bite and then pull up nice and slow," I tell them. "Give them time to get on there tight." When you do pull one up, it opens and closes its pincers to let you know it’d rather be back in the water, eating algae and rubbing against rocks instead of hanging there, scared. You pinch the crawdad between your fingers, and its tail fans open and flips at your skin, as it tries to scuttle away. When it taps you, if you’re not used to it, a jolt goes through your body and you drop the sucker, setting it free. This happens to the Derbez brothers almost every time.

I’ve been fishing for crawdads since I was seven. Dad taught me how because he said it’s important to know in case I ever get lost in the woods. He told me I could eat them or use them to fish with or both. I told the Derbez brothers the same thing. When they get good, we’re going to walk all the way to the end of the creek, catching crawdads as we go. We want to see the exact spot where our water turns into the river’s water, where it stops trickling over rocks, swirls into the mighty current, and starts pulling rusty barges south.

One time I saw a crawdad leave his old body and grow into a new one. I was on the far end of the creek, where the water speeds up a little and spins twigs and fallen leaves towards a tiny waterfall. The crawdad was hiding in between two stones, away from all the others. He started shaking a little and rolled over on his back, moving his legs and pincers like he was trying to get right side up. I didn’t touch him because I could tell he was working on something important. His body cracked just a little, then his pincers and legs worked their way through their old shell. A few minutes later his old shell popped right off, got caught up in the current and twirled its way about a foot downstream until it scraped up against a log and came to a rest. The crawdad, big and fresh, paused and then stretched. He made his way over to the log where his old body rested and nestled up next to it. He waited there for a minute, still, and then snapped up his old body with his left pincer, and then slowly began to eat. I could hear the crunch. Dad said this process is called moulting and crawdads have to do it to make themselves stronger.

"Does eating your fingernails make you stronger then?" I asked.

"No."

"Why not?"

"Because men don’t moult."

There are parts of the creek that are deep enough to swim in. I go with my little brother, Ben, to a cove about 60 paces west of our house. It’s in that cove where we found out Ben’s reflection is not really his reflection. We found out when Ben was swinging across the cove on the rope swing, about to drop into the water, and I saw something shoot across the surface and stop right where Ben dove in. Ben got out of the water, yelling, "Did you see that! Did you see that!"

"Yeah, those colors! All that light!"

Ben looked straight at me. "That light," he said, gasping, out of breath. "That light was a boy!"

The dead boy does not scare us. All he does is make faces at Ben every now and then. Ben believes that as long as he keeps making nasty faces back at him, he’ll leave us alone and let us swim, since, like a dog or a girl kicking your shins, he’s probably just out for attention. But sometimes I think about what I would do if the boy tried pulling Ben into the water with him, into the world spread out across the surface of the creek. There’s no way I could get him back. Truth is, as many times as I’ve seen the dead boy streak by, I still haven’t figured out how he ever got there, to that world that exists somewhere between underwater and the world that holds the air we breathe. My only guess is that he wound up drowning in the creek and while his dead body was sinking to the bottom his soul escaped through his pouty purple lips and only made it up as far as the water’s surface. Maybe it didn’t see any point in going any further or maybe it thought it had gone far enough up already.

IF IT WEREN’T for the dead boy, the year would be ruined. I thought it had already been ruined a good two weeks before we spotted him, to be honest, when Mom left Dad. Pieces of Mom haunted our house for a while. Scraps of paper she’d doodled on rested next to the phone; she drew bubbly flowers and cartoony men, three-dimensional boxes with dolls inside them. Every time I opened the bathroom drawer where Mom kept her perfume, her scent would come swimming out. There was a stain on the carpet next to the couch where she spit out wine laughing at Dad trying to mime like the guy they saw in the park on their second honeymoon. When Dad cleaned, he never vacuumed near the stain. He never even looked at it.

Mom left Dad because she fell in love with another man. When I met him, he shook my hand. His hands are bigger than Dad’s. He shook my hand like I was a man, wrapping his hand all the way around mine and squeezing tight. "Hi, my name’s Ron," he said. At dinner, Mom and Ron sat on the same side of the table, across from me and Ben. Ron kept asking me questions about baseball and school, but I didn’t answer. I just swirled some ketchup around in my mashed potatoes with my fork and didn’t look up. I didn’t look up the whole time we ate. When I finished eating, I leaned back in my chair and saw underneath the table. I saw Mom’s hand on Ron’s thigh; I saw her bare feet on his bare feet. My stomach sank and I felt the mashed potatoes rise up in my throat. I covered my mouth with my hand, the same hand Ron shook, and wanted to cry.

After that dinner, I couldn’t sleep, and I made Ben sneak out with me to the hill behind the community center, which slopes down to the highway. A couple years ago we found a bench seat from an old Cadillac down at the hill’s base, buried partially underground and covered with leaves. We set it up at the top of the hill so that you can sit and watch the cars pass over the wavy valley at night. The hill is covered with enough trees so that when you sit there, you can see the cars but the cars can’t see you. Sometimes the older kids leave a beer behind or forget a pack of cigarettes, and we get a taste of what it’s like to be their age.

That night we found three beers, a new record. They were warm but the cans were clean. We drank the first two then shared the third. We talked about how the seat got to be there in the first place.

"Probably left over from a car wreck," I said. "I’m sure the car rusted and rotted away, leaving nothing but this seat behind."

Ben shook his head as he took a drink. His Adam’s apple leapt with his swallow.

"What do you think then?"

"Well," Ben said, handing me the beer, his hand a little shaky now, "I think it’s from the Indians. Everything they made came from the ground. They had different ways of doing things."

I took a drink, flicked the tab on the can and handed it back to Ben. "You think the Indians grew cars or something?"

"I think they tried, and they sure came close. They grew a seat, just took them a while. Who knows what could’ve happened if they would’ve been here longer." He took the last swig, flicked the tab and it went flying off into the leaves at our feet.

"What makes you say that?"

"Nothing," he said, swallowing. "Probably just the beers talking."

The leaves, yellow and speckled brown, fell from the trees and drifted down the hill. The wind carried them to the highway, where some got plastered onto windshields and got caught underneath wipers, got sent across the state until they disappeared.

Ben and I each took separate ends of the bench and curled up, letting the hum of passing cars lull us to sleep. At home, Dad would always sing to us at night about swinging on stars and bringing moonbeams home in a jar. No matter what, he always sounded happy, even the first night we slept in the house without Mom there. I remember later that night I got up to go to the bathroom and walked by his bedroom. His door was wide open. My parents’ door is never open. I poked my head inside and saw him sleeping alone in that giant bed. I’d never seen him asleep in bed before, only on the couch. There was so much empty space there. His left arm was underneath his pillow and dangled off the side, and his legs were scissored open, spread out but only far enough to take up exactly half the bed. The other side was perfectly made, left untouched. The red light from the alarm clock shone on his face and bounced off his drool.

I DON’T don’t know if it was from sleeping outside or what, but the next day, when we got home and Mom had finished yelling at us, Ben’s liver stopped. I was playing Battleship with him when it happened. His eyes turned dull and yellow like a sick dog’s. I told Mom first before saying anything because I didn’t want to scare him. There was no way he would know unless he walked over to the bathroom and looked in the mirror, and I could keep him from doing that. As long as he couldn’t see, he wouldn’t know; and as long as he didn’t know, he couldn’t hurt.

A liver’s something you can’t grow. You have to get one from another body. I asked the nurse if I could give Ben mine, but she said I need it just as much as Ben does. "That’s why they call it a liver," she said. That made sense medically speaking but I doubted her. I read about this one kid in India who sits in trees all day. He doesn’t sleep, eat, or brush his teeth. All he does is sit around, and yet he’s still alive. I could be like that too if people let me.

The girl was younger than Ben and needed her heart and a lung replaced but couldn’t find anyone to donate them. When she stopped breathing, her parents said to give away her organs, as many as possible. She donated her liver, her kidneys, even her corneas. They just took them right out of her while they were still fresh and put them in other people’s bodies, including Ben’s. Sometimes I look at Ben and wonder if she’s floating around somewhere inside of him. I want to reach my hand down his throat and pull her out.

A few months after he got out of the hospital, near the beginning of winter, Ben was still sick every now and then, sometimes having to lie in bed all day watching "The Price Is Right," waiting for his doctor to come and go so he could earn his banana popsicle.

The creek changes in the winter. The cold turns the water into ice and lays down a blanket of snow, creating another layer between the dead boy’s world and ours. It wasn’t until the snow started to melt and the creek started to turn back into water that I thought about how cold the dead boy must be. I thought about how he probably freezes like a fish in the frozen creek, safe for a while, but then, as the ice melts and the wind skims the water and sends ripples across the surface, he must come close to dying a second death. With Ben sick, the only one who could save him, the only one who even knew about him, was me. I decided to take along one of the Derbez brothers just in case.

There were no leaves on the trees, only icicles. Hiking through the snow had made my pants wet and crunchy, and I could see my breath.

"Breath is spirits in our mouths," Joey Derbez said.

I hung my head back and stared at the cold blue sky. The sun shone into my eyes. When I closed them, colors filled my head. I wondered if Joey would call the colors spirits too but I didn’t bother to ask. I liked thinking of them as colors and nothing more.

"I heard people in Canada ice skate to work on the river," I said.

"Where’d you hear that?"

"National Geographic."

I thought fly-fishing would work best so I took my normal fishing rod out to the creek, baited it with a miniature Reese’s peanut butter cup, let out a bunch of line, and began casting back and forth, barely scratching the surface of the water, dipping the Reese’s in and out of his world.

"Where’d you learn to do that?" Joey asked.

"The Discovery Channel had a special on fly-fishing in Montana."

"Why can’t you just do like we do when we’re cat-fishing?"

"Catfish live on the bottom of the water. This boy lives at the very top." I tried to explain better but it was hard. "You know how you can see the reflection of the trees on the surface there?" I asked, pointing. "Well he lives right in there, in a world so thin you can’t even see it’s there."

Joey looked confused. "I don’t care where he lives, he’s never going to take that soggy chocolate." He was making fun of me but he was right. It wasn’t until I started using Bazooka Joe bubble gum that the dead boy took the bait.

My rod started to shake. "Got him!" I cried, yanking back to set the hook.

He pulled down hard and ran with it. Brilliant streaks of light shot across the surface. I choked up on the rod and dug my feet deep into the snow. He made the line zigzag back and forth like he was autographing the water. I jerked up one final time and thought for sure I’d hooked him good but my line snapped and I fell back, collapsing into the snow.

I wasn’t sure why he didn’t let me pull him out, why he insisted on staying in his creek, alone. Maybe he thought I was messing around with him. Either that or he figured he might as well fight for what he had, just in case that fishing line led someplace worse.

I brushed some snow off my face and looked out to where my line had been. A log bobbed up out of the water. Wrapped around the log was my line, and jammed into the log was my hook, along with a piece of Bazooka Joe bubble gum.

"Ha! That’s what you get!" cried Joey. "You go fishing for spirits in some creek and that’s what you get." He popped a Reese’s into his mouth and laughed an open-mouthed laugh. His tongue was coated in peanut butter and chocolate. "There he is!" Joey yelled, motioning towards the log. "Wave to your dead friend!"

BEN WAS RIGHT about the Indians. There is one who still guards the bench. I see him there when I’m there alone. The Indian never talks to me but he knows I’m there. When I come, he stands up slowly and walks away. He is not a ghost but he has a body that shines bright. The leaves move to the side in waves as he makes his way down the hill. He wades through the deep part of the creek and comes out dry. He crosses the highway over to the open field where high-schoolers sometimes drink beer around a bonfire. He sits down next to the fire and does not speak. Nobody notices. He grows taller and taller as he watches the fire burn, and once everyone clears away and the fire is just a few embers glowing calmly under dead wood, the Indian spreads his stretched body across the field and falls asleep, dissolving into fog by morning.

I once walked the same strip of land the Indian walked, shuffling my feet across the cold ground to make sure it was safe. I walked down the hill, across the frozen creek and across the highway to the field. I raised my arms and stood on my toes to see if I’d grow tall but my feet stayed four feet from my eyes. I lay down facing the moon.

Two tiny glints of light shone over a hill far away, speeding towards me. I pretended they were a pair of shooting stars. I tried to make two wishes but couldn’t even think of one. The car turned off the highway onto the shoulder, stopped and went dark and quiet. A man got out, looked around, and yelled up the hill, "Hey, you up there?"

It was Dad. I didn’t move. Out here, in a field carrying thousands of millions of years of history, he could be calling out to anybody. I ran my hands through the grass, which the night had made damp. I discovered a nickel-sized object and turned it around in my hand, trying to tell if it was a shattered arrowhead or a bottle cap. I couldn’t decide which it was, or even what I wanted it to be. I let it fall out of my hand and stood up.

"Dad?" I cried.

I AM 65 percent water and 35 percent bones and flesh, but if things could pass through me, I would walk across busy highways just for fun and, for 25 cents a pop, I’d let Joey shoot at me with his BB gun. I wonder if the wind would blow my hair back or just go straight through my head, and if that would feel good or if every inch of my skin would feel like my mouth does when I have a cavity. I wonder if I could make it so bad news never hit me, or even better, so no words at all ever hurt me. I wonder if I’d still be able to touch things sometimes, when I really wanted to, or if I’d have to be like that always, no matter what, all the time.