Terry's Gift

On the night he died, Terry Toedtemeier took the stage before yet another audience to talk about his life’s work, photography. Nearly two hundred people had crowded into the Columbia Center for the Arts in Hood River to hear the Portland Art Museum’s veteran curator of photography, a talented photographer in his own right, speak alongside coauthor John Laursen. Images from their new book, Wild Beauty: Photographs of the Columbia River Gorge, 1867–1957, were on display downtown, at the museum, and Toedtemeier and Laursen had been in demand as lecturers.

The program ended with a long ovation, followed by a book signing. As Toedtemeier and Laursen were inscribing copies, Toedtemeier started to tremble, and, as Laursen remembers it, the light just sort of went out of his face. Toedtemeier collapsed and died without ever regaining consciousness.

This happened December 10. Toedtemeier was sixty-one. News of his death stunned the city’s art community. Terry? Dead? Impossible. He was too vital and gifted, too much a bon vivant—a scholar who could act like a tot gone wild. A great piece of art could make him roll on the ground, whooping; a mountain vista might prompt him to gesticulate like a maniac and weep; when confronted with an offense against art, he’d flee to his beloved basalt country, fire guns at the heavens, and rage like Lear on the heath. He died just as dramatically, of a coronary coup de grâce.

No other Portlander has left the city quite the kind of artistic legacy that Toedtemeier did. Here are five of his key contributions.

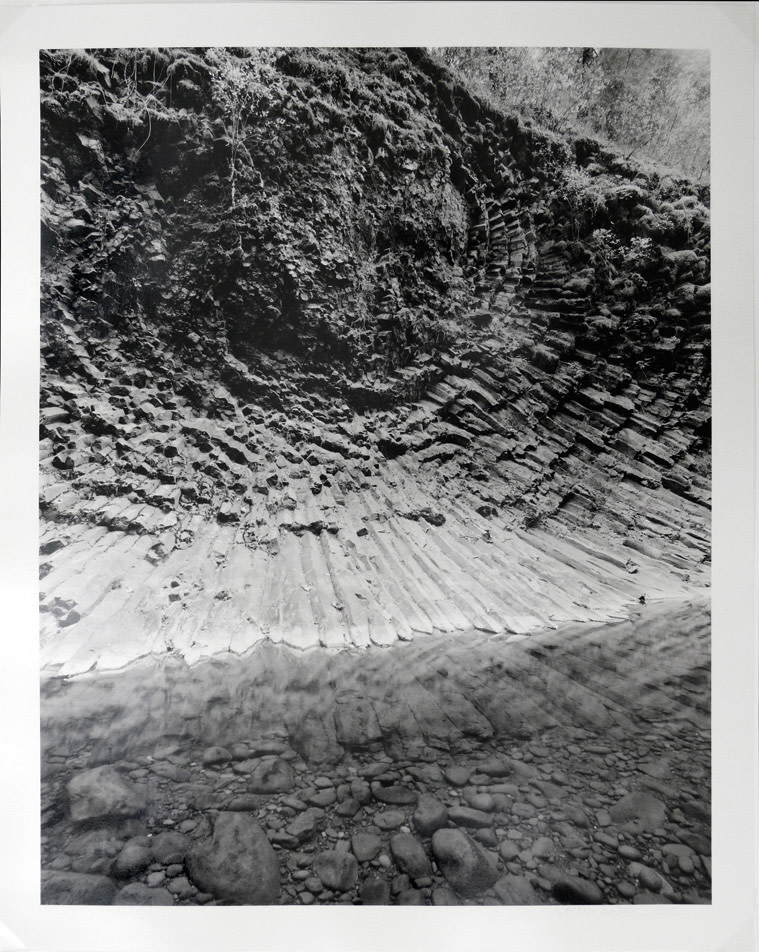

Radical Fractures, Basalt, Mollala River, Clackamas County, Oregon 2002, Courtesy Portland Art Museum

THE BOOK Wild Beauty was Toedtemeier’s magnum opus. It contains 134 images that show the Columbia River Gorge’s transformation from the primal scene Lewis and Clark witnessed to the developed present. Among the featured photographers is Carleton E. Watkins, the revered nineteenth-century landscape photographer Toedtemeier idolized. Together, the photos tell a story not just of natural beauty but also of the terrible wonder of dynamited boulders and falls now flooded. Wild Beauty is a record of how Portlanders historically have interacted with the landscape, a chronicle of the art of photography, and a study of what Oregon lost—and managed to save. The book won the five-state Pacific Northwest Book Award, and the Oregonian named it the top Northwest book of 2008. The first printing sold out; the second was just released, in March.

THE COLLECTION During his twenty-three years as PAM’s curator of photography, Toedtemeier acquired rare, early Oregon and Northwest images as well as those by contemporary photographers working in a range of styles, from the minimalist black-and-white landscapes of Robert Adams to the theatrical fictions of Cindy Sherman and Carrie Mae Weems. The collection now contains more than five thousand brilliantly chosen photos, including those of famous photographers like Ansel Adams, Imogen Cunningham, and Minor White, and of lesser-known masters. “Terry pioneered for the people of Oregon the idea that photographs could be works of art,” says the influential Weston Naef, the curator emeritus of photography at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.

HIS OWN PHOTOGRAPHS Technically impeccable, fastidiously developed, polished to the smallest pebble on a beach, Toedtemeier’s photographs contain a preternatural sharpness and thunder with his passion for the Oregon landscape. His epochal vistas of sea caves, natural arches, and vast rock formations comprise an otherworldly corpus. His art was particularly informed by his scientific eye (he studied geology in college) and by the history of Western photography. Since his death, a patron has bought his work for the Philadelphia Art Museum; his photographs already had found a home at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, and the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.

Sea Cave, Terminus of Cape Lookout 2000, Courtesy PDX Contemporary Art

On the morning of the day he died, Toedtemeier got a call from MacArthur “genius grant” recipient Robert Adams, Oregon’s most famous photographer. Adams congratulated Toedtemeier on Wild Beauty and urged him to do a book of his own photos right away. Toedtemeier had, in fact, begun working on a volume of coastal photos when he died. Sandra S. Philips, the renowned senior curator of photography at the San Francisco MOMA, has offered to help Toedtemeier’s wife, Prudence Roberts, along with Laursen, expand the project into a book tentatively titled Transcending Time. Roberts, PAM’s former curator of American art and a Portland Community College art history professor, has begun the considerable task of cataloging her late husband’s prints.

PROOF THAT PASSION AND WIT CAN TRANSCEND TRAINING AND MONEY Toedtemeier had no formal art training and practically no budget when he began building PAM’s photography collection. As a curator, he relied on the whirlwind force of his persuasiveness. Collectors donated their masterpieces because Toedtemeier had a way of explaining why they were important and how they fit into history, and of spreading enthusiasm for bringing them out of obscurity. “Terry was one of the last of a particular twentieth-century breed of photographer, curator, collector, and impresario,” says John S. Weber, PAM’s former curator of contemporary art and now Dayton Director of the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College, in Saratoga Springs, New York. “[These were] people who invented themselves with little or no formal training of the sort we see today. I’m talking about people like Ansel Adams, Edward Steichen, and Alfred Stieglitz.”

PERSPECTIVE Toedtemeier’s work can teach us how to see more deeply. As a curator, Toedtemeier focused on the entire context of a photo, including the artist’s point of view and the history of the subject. A few weeks before he died, he promised to show Naef, the retired Getty curator, his latest discovery: Carleton Watkins’s vantage points for classic 1867 shots near what is now Bonneville Dam. (The US Postal Service selected one of these shots for its 2002 Masters of American Photography stamp series.) “Terry had sleuthed the now-submerged places where Watkins had positioned his camera,” Naef says.

Alas, the meeting with Toedtemeier never took place. On the night of December 10, Laursen and Toedtemeier drove out to Hood River together for their lecture. Laursen remembers his friend pointing out the moon—“this ghostly shape behind the clouds”—and saying, “I’ve never seen it exactly that way before.”

Much later that night, someone drove Laursen home. The moon was still up, but Terry was gone.