The Ballad of Fred and Toody

TWO EYES. TWO WIDE EYES dilating in the dark, glued to every shimmying, twitching, undulating move of this banshee, this woman—this black locomotive on fire—bouncing all over the stage like a goddamn moth on a bug zapper. She is electricity. She is religion. She is drugs. She is everything.

The year is 1960, and a 12-year-old Fred Cole is standing in a concert hall having his mind blown by the soul explosion of the Ike and Tina Turner Revue.

The fact that it’s Ike and Tina’s pre-“Proud Mary” heyday is the only way to explain why they’re playing a show in Klamath Falls. Cole gobbled up the tickets like they were salvation, but the rest of the town is not so hip. When the curtain goes up, there are maybe 20 other people in attendance. Ike and Tina are used to sweating and shaking for the masses, but here in the green expanse of Southern Oregon, they’re playing to crickets.

Tina can see the audience. She can see the swaths of empty seats. And yet she does not stop shaking. Does not stop dipping those shoulders. Does not stop belting out the rafter-rattling blues like her life depends on it.

There will be other monumental touchstones in Cole’s life—seeing the Beatles, sharing a bottle of Southern Comfort with Janis Joplin, meeting his wife-slash-bassist-slash-soul-mate, Toody—but it was here, in Klamath Falls, that his rock ’n’ roll heart first chugged and heaved into motion.

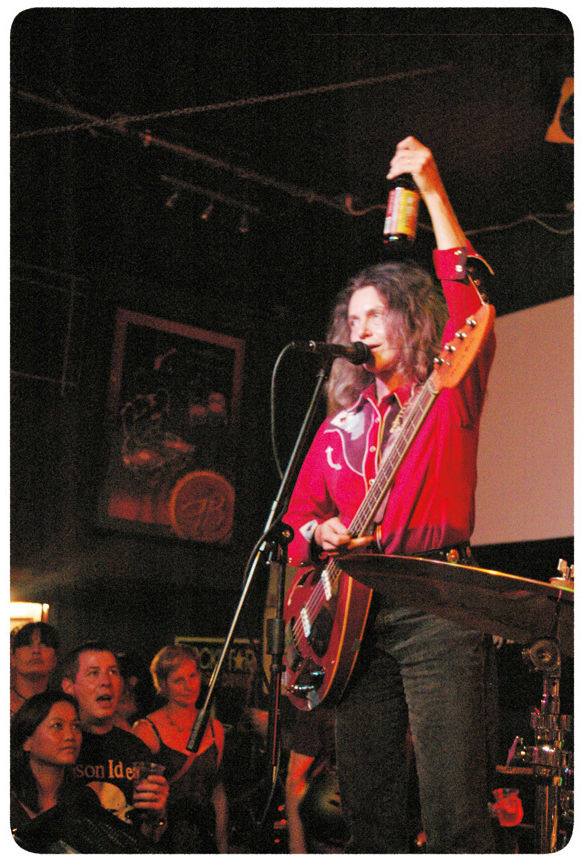

Forty-eight years later, Cole, the 60-year-old rocker from Clackamas, stands on a stage in Salt Lake City. He straps on his guitar and steps into the spotlight as he’s done thousands of times before. To Cole’s right, Kelly Halliburton settles his thick frame behind the drum kit. Ink-black hair hanging in his eyes, Halliburton looks like a Visigoth holding Q-tips. Toody, Cole’s 60-year-old wife of 42 years and bandmate for 31, tosses her gray hair out of her face with a whip of her neck, rolls up the sleeves of her red western shirt, and plugs in her ancient Vox Wyman bass (named for the Rolling Stones’ ex-bassist, Bill Wyman). She looks kind of like Patti Smith: an utter badass. A dull hum rumbles through the amplifier. Cole raises his eyes to the crowd.

Pierced Arrows performs.

Image: Linda Lund

But there is no crowd. It’s a Tina-in-Klamath-Falls kind of night. When booking the tour for Fred and Toody’s latest musical endeavor, Pierced Arrows, their agents didn’t pay any particular attention to the fact that the band was playing Salt Lake City on a Monday night. Mondays were typically light, sure, but it was a paying gig—gas money and dinner at the least. Except that in Salt Lake City, the epicenter of all things Mormon, Monday night is Family Home Evening, reserved for meals, prayer, and devotionals with relatives. Even for the less-than-pious, it’s tradition. Nobody goes out.

Looking out at the empty room, a lot of bands would’ve packed it in. Particularly when three of the four paying customers on this night end up being friends of the opening act and bail immediately after that group’s set is over. But Fred Cole plugs in his red Guild S-200 Thunderbird, looks the lone patron in the eye, and begins hammering on a chord. Goddamnit, he thinks to himself. If Tina can do it, I can do it. He presses his lips against the microphone, opens his mouth, and begins to scream.

WHEN COLE FORMED Pierced Arrows in 2007, it marked at least the 15th different moniker he’s performed under since 1964. The band’s upcoming album, Descending Shadows, is—as near as anybody can tell—Cole’s 35th collection of songs, its 11 tracks pushing his total number of compositions toward 300. And when Pierced Arrows finishes its current West Coast tour, Cole’s personal odometer will flip further into the hundreds of thousands of miles—most of them seen from behind the windshield of a rickety white Chevy van that runs on diesel and fervent prayer. Touring has taken him across the United States, Germany, Spain, Mexico, Australia, and a few countries in Eastern Europe whose names he can’t pronounce.

Cole is what’s known in rock ’n’ roll circles as a lifer: a living, breathing, chain-smoking, whiskey-drinking relic of an American art form’s past, present, and future. He once roomed with Stevie Wonder; he’s played bills with the Doors; and his songs have been covered by alt-rock superstars like Cat Power and Pearl Jam. For most of the past two decades he’s been making jittery punk, hard rock, and blues anthems under the moniker Dead Moon—with Toody laying down the bass line and contributing vocals. He’s recorded and cut his own records in the home he built outside of Clackamas, using the same lathe that carved the Kingsmen’s iconic “Louie, Louie” into vinyl.

But you’ve probably never heard of Fred Cole. Most people haven’t. His albums don’t sell. His cheaply recorded, hook-heavy hard rock is an acquired taste. He’s never had a hit. But among musicians and connoisseurs—especially those in the Northwest—Cole is considered both legend and curiosity, an archetype for the DIY model that, 34 years after he started living out its laws of music-first creative independence, has now become an ethos (even a marketing ploy) in thriving music scenes like Portland’s. He was among the first of his breed, and considering his age and his drive to keep playing past the age of retirement, maybe the last of his breed. After all, it’s easy to be hypnotized by rock when you’re young, when the promise of sex and drugs and adventure is enough to sustain a band on mad dashes across the country. But to keep doing it for 45 years?

Image: William Landers

“It’s easy to underestimate the effect [Fred and Toody] had,” says Mike King, a Portland-based poster artist and designer (and retired musician) who’s worked with acts like Iggy Pop, Ben Harper, and Jack Johnson. “When I started playing music in the late ’70s, they ran an equipment store called Captain Whizeagle’s. It was a hub for people who wanted to make weirdo music. I wanted to make punk rock, and that’s where I bought my first bass. To still be doing what they’re doing,” he pauses, searching for the words. “I mean, to still be getting in a van and driving to Boise? I’m as DIY as the next guy, but I’m not that DIY.”

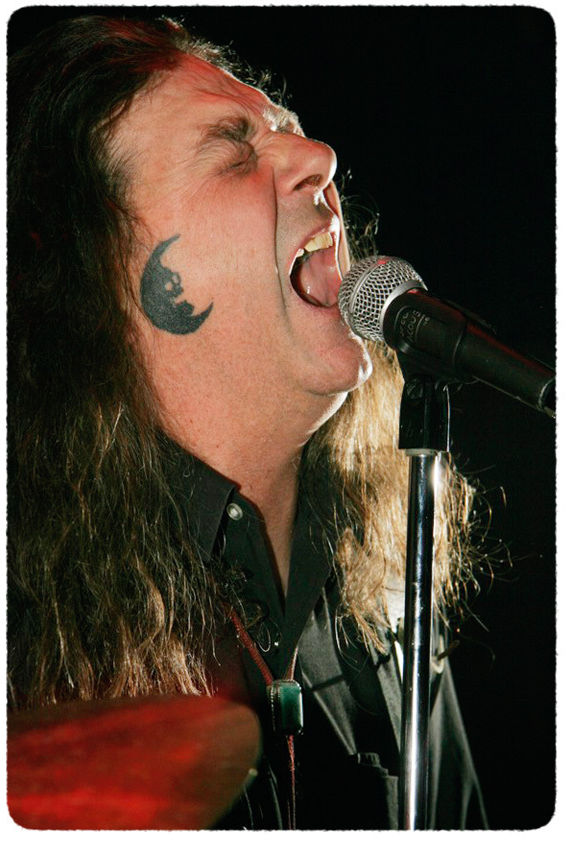

The wear and tear of four decades of this life have shaped Cole’s body like a nicotine-stained glacier. His left shoulder stoops slightly from having a guitar slung over it for 30 years. His blue hound-dog eyes rest on folded beds of skin darkened by days and nights of sound checks, dirty motel rooms, and pitch-black highways. His voice, a soulful yelp when he was 16, has been ravaged by screaming and smokes, leaving it a raspy approximation of Robert Plant and a braying mule. He is basically deaf and needs a hearing aid to make casual conversation tolerable. And then there’s the fist-size tattoo on his right cheek of a skull cradled in the nook of a crescent moon, the logo of his beloved former band, lo-fi rock folk-heroes Dead Moon.

But Cole still has all his hair, which is more than most 60-year-olds can say. When not corralled inside his trademark cowboy hat—so beaten up that it looks more like a wizard’s hat—the tresses run off his scalp and down past his shoulders in enviable strands of rust, black, and gray. He had to pull a tooth backstage in Germany a few years back, and another is glued to its neighbor to keep it rooted in his mouth. But the other 31 are still there. Above all, though, he still has his songs. Without them, Cole might be a delusional old coot. But over the course of his career, he’s wielded his dark, poetic gift like an ax, slamming home jagged slabs of sing-along rock and punk about life, death, love, and—above all else—grit-toothed perseverance. The music rumbles. It soars. And even when it plunges, it does so with a stiff middle finger.

His cult is small, but it is fanatic. It includes people like Eddie Vedder and Dave Grohl. And as long as they’re out there—and as long as Toody is plugged in right beside him—Cole will keep playing. This is all he knows. There is no end in sight, save one.

“Once I play the moon and I’m a hundred years old, then yeah,” he says, sucking a cigarette down to the filter. “I’m outta here.”

Fred and Toody on their wedding day, June 14, 1967.

Image: the Coles.

FRED COLE’S PATH TO BECOMING a Portland underground rock deity was a meandering one. Born in Tacoma in 1948, he bounced down to Klamath Falls when his parents split up, and ended up living in Las Vegas as a teenager after his mom took a job working as a fecal tester for the Atomic Energy Commission. The job involved an unpleasant 60-mile bus trip every day to Mercury, a radiation-riddled town near the Nevada nuclear test site, where she spent hours digging through animal waste for signs of contamination.

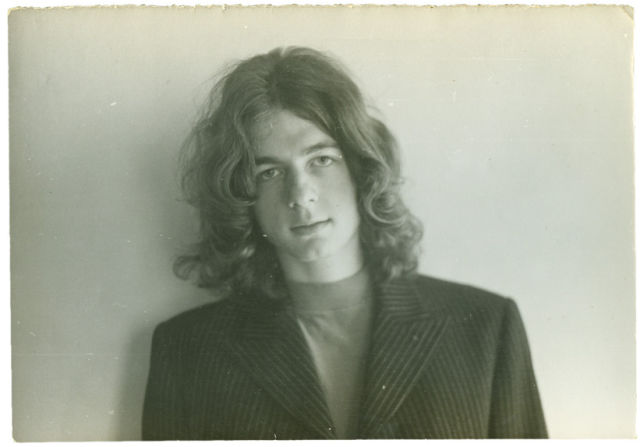

Cole got kicked out of school four days into his junior year. He’d just seen the Beatles live in Vegas and decided to grow his hair out long. The principal of his high school gave him an ultimatum: cut your hair or else. Cole’s response was not surprising. “I said, ‘Fuck you, I’m outta here.’”

By 16, Cole was already a garage-band veteran: the Barracudas, the Little Red Roosters, the Lords. He played solo shows under the name Deep Soul Cole with an all-black rhythm-and-blues band. On the strength of his soulful adolescent warbling, he was billed as “the white Stevie Wonder.” Sometimes he would make his entrance from the back of the hall, walking on the tops of seats and over heads toward the microphone while the band blasted away onstage. He learned how to play strip clubs, how to get arrested, how to escape a girlfriend’s angry father by jumping out of a second-floor window.

At 17, he and four other Vegas teens formed the Weeds, a slightly psychedelic rock band in the vein of the Zombies. After a year of packing midsize local venues, they made a break for San Francisco in 1966 to plug into the exploding Haight-Ashbury scene. A Vegas disc jockey promised them a slot opening for the Jeff Beck–era Yardbirds at the Fillmore—but when they showed up, nobody had heard of the Weeds. While they were figuring out their next move, a car jumped the sidewalk, sending the five members of the band scrambling for cover. Citing bad juju, the Weeds hopped into their van, pointed it north, and punched the gas. They sputtered to a stop 635 miles later, hungry, broke, and frustrated. Fred Cole had finally made it to Portland.

It took a few months of bandaging their pride at the Rose City’s now-defunct Folksinger club, but the Weeds finally returned to the road in 1967. After a show in Los Angeles, they were taken under the wing of Lord Tim Hudson, a scenester DJ who ran with the Beatles and credited himself with coining the term “flower power.” Hudson got the band signed to the Uni label, a subsidiary of MCA Records. He even convinced them to change their name to the Lollipop Shoppe in order to cash in on the bubblegum rock running wild on the airwaves at the time.

The maneuver worked. The Lollipop Shoppe scored a minor hit with “You Must Be a Witch”; had a brief appearance in a biker B-movie, Angels from Hell; and opened dates for the Doors, Buffalo Springfield, Steppenwolf, and Big Brother and the Holding Company, fronted by Janis Joplin. Cole even had a run-in with Joplin that helped give a sobering dash of clarity to the much more personal project he’d been working on back home.

A baby-faced Fred circa 1969.

Image: the Coles.

For the first time since he saw Tina Turner perform, something besides the seductive power of rock ’n’ roll had wriggled its come-hither finger at Fred Cole. He had married this girl back in Portland, see, and he was deep in the throes of love; Joplin, however, was dangling from its gallows. In the drunken conversation between the lifer and the soon-to-be casualty, Cole had an epiphany. “Janis was totally unconfident about her looks, her vocals, all the rest of it,” he says. “And she was in love with Sam [Andrew from Big Brother], and it was unreciprocated. She was really hitting the Southern Comfort. She was like, ‘It’s all fucked unless you have somebody to love. Do you have somebody to love?’ I said, ‘Yes, I do. Back in Portland.’”

Her name was Kathleen Conner. She worked the door at the Crystal Ballroom, right around the corner from the Folksinger club. She had big green eyes, good taste in music, and a problem with authority. Her friends called her Toody.

The 18-year-olds were married by a justice of the peace in a small family ceremony on June 14, 1967, their union symbolized by a six-dollar gold ring. Cole’s relationship with Lord Tim would soon fizzle. The Weeds would quickly be dropped by Uni, and would eventually splinter. But the love song Cole was composing with Toody seemed like the kind of thing that was built to last.

IT’S 4:30 IN THE AFTERNOON on a Friday, and Cappy—that’s what Cole’s grandkids call him—is getting his drink on out on the back porch of the house. Except for our wicker seats, the rest of the deck is a graveyard of discarded equipment: VCRs, stereo parts, toaster ovens, a microwave. The weeds are grown high, biting flies dive-bomb exposed skin, moss hangs from everything, and off in the distance, families of beavers have turned a small creek into a swollen pond. Cole twiddles with the dials on a dusty boom box, trying to blast a burned copy of Pierced Arrows’ new album into the wilderness. He is a monkey working an abacus: even with his glasses on, he keeps pushing the wrong button. The player stops and starts, fast-forwards and reverses, then finally shuts off. Toody hovers over him, giving instructions. Nothing. She cups her hands, that band of cheap gold still managing just a dab of luster, and yells. “He doesn’t have his hearing aid in,” she says, loudly, since he can’t hear us. “I’ve learned to deal with it. I just yell. But onstage, he has to turn his monitor up louder than God.”

Cole must’ve heard something Toody said, because the music finally kicks into gear and a grizzly rocker bleeds from the speakers. Like his other dozens of releases, it sounds good. Unlike the other dozens of releases, this one might have a chance of reaching a larger audience.

Toody onstage in Australia with her trademark Vox Wyman bass.

Image: the Coles.

Whether on his own Whizeagle or Tombstone record labels, Cole has mostly self-released music since 1975, but he’s been approached by New York label Vice for the rights to distribute this latest record. If it happens (Christopher Roberts, Vice’s creative content director, refused comment when contacted), Pierced Arrows will join a roster of far more “hip” bands like Black Lips, the Raveonettes, and the Streets. Bands with style, endorsements, and fancy haircuts. Lucrative bands. It’s an odd but deserving fit, and maybe the only real sign that Cole’s age might be softening his rigid DIY stance. “You don’t make as much money,” he explains, “but the advantage is we don’t have to deal with the promo and all the work of just putting something out. It’s a nightmare trying to do all that stuff between tours.”

Money isn’t a big concern for Cole. He and Toody have no health or life insurance, and they’re hoping that rents from the convenience store and sandwich shop currently residing in the small block of western-themed buildings nicknamed “Tombstone” that Cole built in Clackamas will be enough to fund their retirement. It helps that they own everything around them. Cole constructed the home himself on 21.5 acres, beginning in the late 1970s. He and Toody raised all three of their children here, living in tents, peeing in bushes, and cooking over an open fire for months at a time during construction. At one point, the county threatened to tear down the house. Cole stood at the top of his driveway with a shotgun and waited; the authorities never showed. But for a brief sojourn to Canada’s Yukon Territory—spurred by a fit of frustration with the music business, the family left with just an ax, a broken chain saw, and a tent—the Coles have lived here ever since.

Lacquered in moss and mostly unpainted, the house is not a thing of beauty—it’s surrounded by the rusting hulls of cars and a pool-house-turned-mosquito-Valhalla—but it’s functional. Besides, it’s what lies behind the door that’s amazing: there, past the hand-laid tiles and mismatched pieces of wood (the sign from Captain Whizeagle’s forms the entryway ceiling), is a one-man shrine to rock ’n’ roll. Old 45s line the walls; concert posters and flyers from almost all of Cole’s bands—the Rats, Zipper, King Bee, the Weeds, Dead Moon, Pierced Arrows—stand in for wallpaper; band and family photographs hang in every nook and cranny; world maps with a constellation of pushpins mark the places he and Toody have played. A dusty but functional Galaga arcade video game stands waiting in the living room for a quarter to bring it to life.

Cole invites me to give myself a tour of the upstairs, where he keeps the record-cutting lathe. Naturally, when given the chance to see a mythical relic of rock like the machine that created “Louie, Louie,” you go. But Cole is over it. He is history. So he and Toody stay out on the porch, relaxing while they can. Cigarettes, beer, sweet Yukon Jack whiskey by the shot glass. It’s been a busy week, what with the rushing to get the CD ready for Vice, packing for a 20-day vacation that will eventually end in Vegas, and attending their granddaughter’s ballet recital at St. Mary’s Academy, Oregon’s lone remaining single-gender school.

“We get funny looks when we go to a place like that, but whatever,” Cole says. “Actually, one of the women who works at the ballet school came up to us after the dance. She’d been at our show the night before. It’s virtually impossible to go out and not see somebody we know.”

Fred and Toody with son Weeden after completing the 2008 Portland Marathon. Not seen: the post-race smoke.

Image: the Coles.

Toody passes the bottle around again, filling our glasses. “We never really even got into this,” she says, nodding at the near-empty handle of Yukon, “until later in life. But at this point, you get old and cynical and haggard enough that you need something to mellow you out. We were just too busy with the kids to get into dope.”

In the 2004 documentary Unknown Passage: The Dead Moon Story, Shane, at 38 their youngest son, describes his childhood. “Growing up, my parents were quite the opposite of the normal mother and father that you would see,” he says. “They always stood out, and at times that would be somewhat embarrassing as you got older. But when we were a lot younger, it was always really cool because they were so different than everybody else.”

As wild as their upbringing must have been, each of Fred and Toody’s children—Amanda (41), Weeden (40), and Shane—have fallen as far as possible from the family tree. Weeden is studying to get his degree in drug and alcohol counseling (he’s living with his parents while he finishes school), Amanda is married to a lawyer for Nike, and Shane works for the Internal Revenue Service. He busts mom-and-pop businesses. Businesses just like his parents’.

But there is hope that the Coles’ musical heritage will live on. Weeden’s 9-year-old son, Christopher, wanders out of the house. He’s holding a digital tape recorder in one hand and a Zippo lighter in the other, practicing the ceaselessly cool one-flip-ignition trick. He hits Play on the recorder to show off his latest creation, a ditty about a girl in school whom he has a crush on, which he delivers in great gravelly burps. Wailing on the guitar in the background is his grandfather, Cappy.

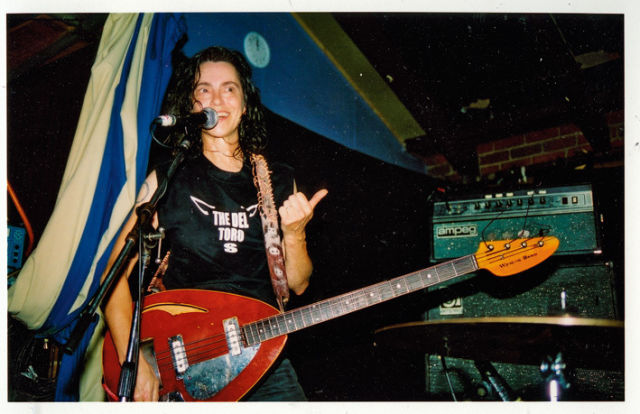

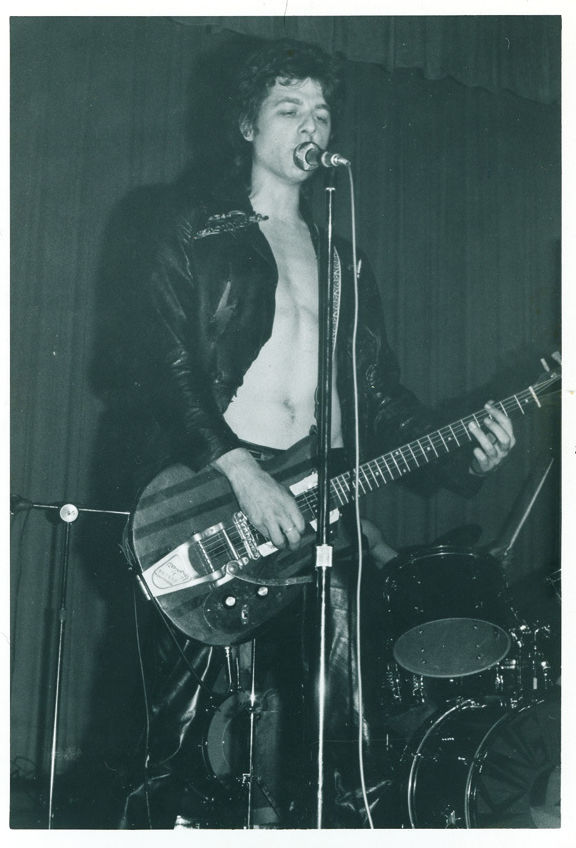

Fred onstage in 1978 with his band Zap Spangler.

Image: the Coles.

THE MOON SQUATS OVER THE ATLANTIC OCEAN, the night cutting New York’s August heat just enough to cool the crowd’s sweat into a salty shell on the skin. The year is 2000, and inside an amphitheater perched right over the breakers of the incoming tide, thousands of people are singing along to one of Cole’s songs, “It’s OK.” Of course, they don’t know they’re singing along to one of his songs. They don’t even know who Fred Cole is. Onstage, Pearl Jam’s Eddie Vedder is leading the crowd in a sing-along tutorial. “I’m gonna give you a part,” he says, the tail end of the Pearl Jam song “Daughter” morphing into a skeletal, shuffling beat. “So I say, ‘It’s okayyyy,’” he sings. “And you say, ‘It’s okaaa-ayyyyyyy.’”

A couple of impromptu run-throughs and the give-and-take is pieced together. The band kicks into a slightly higher gear. Vedder pulls out a hand-scrawled lyric sheet and begins singing Toody’s Patti Smith-esque incantation from the original version. “This is my chance, this is my life and my opening hour. This is my choice, this is my voice, there may be no tomorrow.” Behind him, the rest of the band begins a slow-building crescendo. Vedder begins to growl. “This is my plea, this is my need, this is my time for standing free. This is my step, this is my depth in a world demanding of me … but it’s OK.”

And 20,000 voices answer back: “It’s okaaa-ayyyyyyy.” Spotlights swell, goose bumps sharpen, and a bona fide moment is shared among the assembled. Cole wrote the song for his daughter, Amanda, as a spunky ode to tenacity in the face of life; Pearl Jam’s take is more of an epic catharsis, a tribute to the nine people who died at one of the band’s festival shows in Roskilde, Denmark. “Eddie’s a real personal guy, and that just threw him for a loop,” Toody says of the Roskilde deaths. “He’s covered a few of our songs and comes to see us play sometimes. The last time we saw him, he wanted to let me know that he’s OK. He’s got a little daughter named Olivia and thank you so much.”

Pearl Jam is just the best known of the bands that have adopted Cole’s jagged anthems as their own. Whispery singer-songwriter Cat Power (aka Chan Marshall) covered “Johnny’s Got a Gun,” and Atlanta alt-rockers Black Lips do a version of “You Must Be a Witch.” There’s a Dead Moon tribute band in the Netherlands, and when the Foo Fighters roared through town a few years ago, Dave Grohl used a bit of between-song banter to remark that the best thing about Portland was the fact that Dead Moon was from here.

“IT’S HARD TO EXPLAIN how cool [Fred] is or how inspiring he is to me,” says Portland author Willy Vlautin, whose books The Motel Life and Northline share Fred and Toody’s unlikely fascination with the “Biggest Little City in the World,” Reno. Vlautin’s side project, the band Richmond Fontaine, even wrote a tune called “A Song for Dead Moon.” “Fred’s the kind of rock star you want to be. He loves his wife, lives how he wants, built his own house. I mean, it’s better than shooting up with a 15-year-old girl or some shit.”

“They’re definitely stalwarts of the Portland scene,” says Alicia J. Rose, a local photographer and musician who co-owns and books bands for Mississippi Studios. “But they could probably care less what anyone thinks. That’s the attitude that has filtered down into the scene that thrives today.”

Drummer Kelly Halliburton helps anchor Fred and Toody’s latest incarnation, Pierced Arrows.

Image: Linda Lund

As respectful as the covers and odes are, nothing beats pure, undistilled, shambolic Fred Cole. So, when Pierced Arrows play a show on a night in early June this year, the faithful cram into Worksound, an art gallery and concert space in the dregs of Southeast Portland. The crowd is a motley mix of iodine-haired teenagers who never got a chance to see Dead Moon, bearded 20-somethings in western shirts who were raised on the bands’ songs, and old-school punks in tattoos and leather who still remember Cole’s older bands, like the Rats and Zipper.

Four songs in, the band begins churning out a new one called “Let It Rain.” It’s one of Cole’s patented moves, a pick-yourself-up-by-your-shitkickers magnum opus. A minute in and the audience, which had previously seemed more concerned with the IV bag art installation in the corner, rouses to attention. Heads bob, necks crane to better hear the lyrics. Even through the sludgy PA, the song is something special. Something archetypal, something transcending all fads and styles. Something for the cult of Fred Cole.

“Don’t waste your thoughts on failure,” Cole bleats as Toody and Kelly beat the song into submission. “That’s a nowhere scene. Go for what you want the most, it’s the only way you’re free.”

The music swells and the crowd begins pumping PBRs in the air and singing along to the chorus: Let it rain! Let it rain! Wash away the pain!

YOUR MARRIAGE IS GOING TO FIZZLE. Your band will break up. Your body will break down. And you will live out your life as an increasing series of compromises, saddled with things you have to do instead of things you want to do. This is reality, we’re told. And we accept it. It’s normal.

But then you find yourself in the middle of Clackamas, drunk on sweet Canadian whiskey and rethinking the whole thing, because, by simply sitting here—half in the bag, ripping cigs, listening to a battered boom box—Fred and Toody are proving that it doesn’t have to be this way. Old age is not a death sentence. You can follow your muse—no matter how difficult the path. You don’t have to give up your guitar for a BlackBerry. You don’t have to trade in Pearl Jam for Perry Como. And above everything else, you can still be in love.

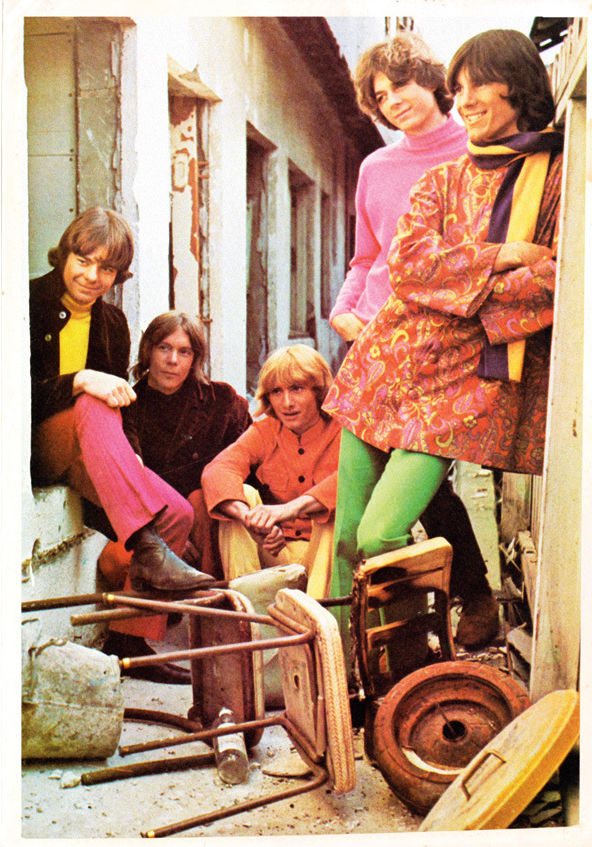

The Lollipop Shoppe in 1968. That’s Fred in pink.

Image: the Coles.

To be sure, Toody is the only thing Fred has ever loved more than rock ’n’ roll. And although Fred says he asked her to start touring with him in the Rats back in 1978 because he was tired of dealing with a rotating cast of flaky bassists, it’s not hard to imagine that he also missed her when he was gone. Even now, the two seem like they’d be lost without each other. Toody knows Fred’s stories better than he does, often correcting him—even the tales about things she didn’t witness. And man, does she laugh. No matter the situation—cockroaches in the motel room, the tendonitis in her right hand, the butting of heads—she postscripts every story with a raspy cackle.

“For us, the 24/7 thing has always worked,” Toody explains. “It’s what we both need, what we’re both able to give, and what we both want. Most people probably couldn’t handle it. He’s a Virgo, I’m a Capricorn; I’m a procrastinator, always late—but him? You must be punctual. What feels like 30 seconds for me feels like 10 minutes for him. It frustrates the hell out of him. But I’m his biggest fan, and I think he’s my biggest fan.”

Forty-two years on, Fred still writes songs for Toody, and, for her part, she says the flattery never gets old. Neither does the shit-talk. As we walk through the backyard to see the lake built by beavers, Fred begins singing a line from a new song, “Zip My Lip”: “Every time we’re one-on-one, you just sit there playing dumb.” And here Toody jumps in: “Zip my lip and let it ride, anymore it’s no surprise.”

“That’s basically us,” Toody laughs, slapping Fred on the thigh. “When you’ve been married 42 years, you’ll understand.”

This year, Fred and Toody celebrated their anniversary like they always do: they locked the door, unplugged the phone, uncorked a bottle of champagne, and had dinner in bed while watching movies. Fred did the cooking on his George Foreman grill: steak, asparagus, potatoes, and crab meat.

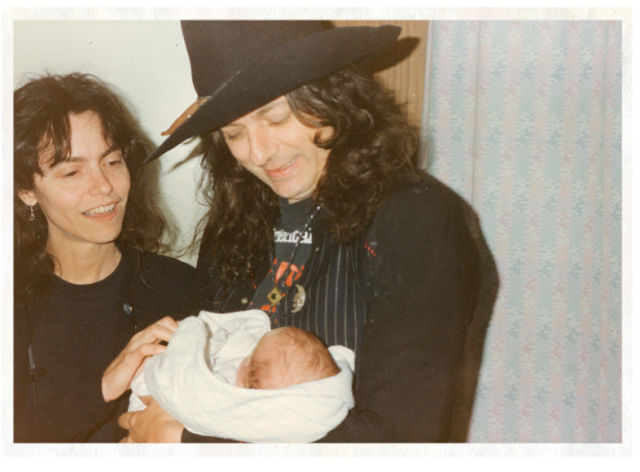

Fred and Toody hold Morgan, their first grandchild.

Image: the Coles.

TWO DAYS LATER, they hopped back in the tour van, headed not for a show, but for a vacation, a rambling 20-day excursion that will take them to the Oregon Vortex in Southern Oregon, Florence, Arizona, Vegas, and a bunch of Indian casinos along the way—all of it an effort to relax in preparation for the glut of touring that will accompany the new record. It’s the same routine they’ve been following for 31 years.

In fact, the only thing different now is that they’re entitled to have a nurse and an oxygen tank on hand when playing a gig in a place like the Netherlands. You know, because they’re old.

It’s a subtle reminder of their advancing years that makes Toody giggle—and pisses Fred off to no end. It’s why he and Toody ran the Portland marathon last year, smoking cigarettes at both the start and finish lines: spite. “You think I’m gonna have anything left in this body?” he asks. “I’m using every ounce of everything I’ve got, and I’m not gonna make anybody else suffer with these parts. They’re mine. I’m very selfish … with my guitar. My amp. And I’m more selfish than anything else on the planet about Toody. I ain’t sharing her with anybody.”

And so, on a battered wicker love seat on a back porch in an overgrown yard somewhere near Clackamas, this love song continues. A grandson circles the two of them, belching out the punch line to a joke, as Gram and Cappy, a pair of aging rock stars, settle further into their late-afternoon drunk. Their knees rub against each other flirtatiously, denim on denim. Birds sing. The butts pile up and the Yukon dwindles. “I love you, sweetie,” Fred says, placing a kiss on Toody’s forehead. She meets his eyes, lightly slugs him in the arm, and smiles: “I love you too, asshole.”