State of the Game

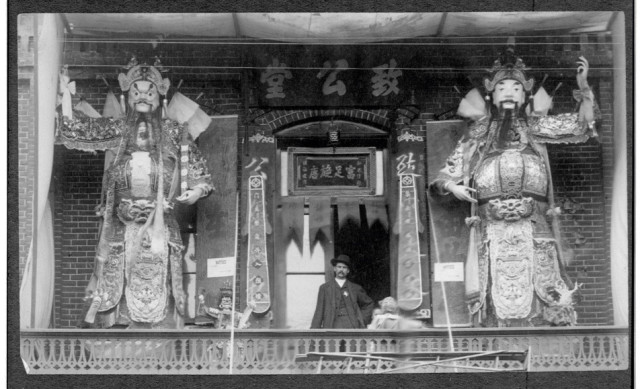

Image: Historic Photoarchives.com

With November’s pounding defeat of Measure 75, which would have authorized the state’s first private nontribal casino, and the plummeting of annual lottery revenues by roughly 15 percent since 2008, Oregon’s long winning streak with gambling finally may be turning cold.

Just don’t bet on it.

Oregon isn’t Nevada or New Jersey, but the Beaver State’s relationship with the sporting life is an old marriage. Its known history begins with Native Americans: tribes from across the entire West converged at major trading centers along the Columbia River, particularly at The Dalles, and wagered furs, shells, food, clothes, and slaves in games of chance and athletic prowess. For the tribes, gambling was a full-fledged part of the economy, for everyone, just like it is for Oregon now.

As Christian missionaries squelched Indian gambling, other immigrants brought new games to the table—the sort played in the back rooms of Portland bars and Chinese lottery dens. By the 1920s, reformers succeeded here, too, in outlawing most forms of gambling in the city. Yet the playing went on, and with it a rising tide of graft, greed, and violent territorial disputes that finally crested in 1957, when Robert Kennedy hauled dozens of Portland officials and criminals to Washington for televised hearings in the US Senate.

Now that gambling is legal for both tribes and the Oregon Lottery, the displays of wealth, power, and territorial imperative have been rewoven into both cultures’ fabric in less violent, more transparent, but still very muscular ways: Oregon has more noncasino video gambling machines than any other state. It ranks fourth in the country for the state budget’s reliance on lottery revenues. Of the profits reaped from Spirit Mountain Casino since it opened 15 years ago, the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde have donated more than $50 million to Oregon nonprofits. And over the past six months, those tribes made some bets of their own, sending $50,000 to John Kitzhaber and $10,000 to Chris Dudley, in part because both candidates for governor opposed a rival casino proposed for the Columbia Gorge.

Oregonians like to play. And so we offer this look back at the historical Indian games, at the city’s dark years of graft and corruption, at the rise of legal gambling, and, last but not least, at the odds for the next big expansion of our game—the proposed Columbia River Resort Casino—the decision forwhich, odds are, will be made any day (maybe even as our magazine rolls off the press).

Ante up!

THE REAL DEAL: TIMELINE OF OREGON GAMBLING

1805-43

Early explorers encounter Native Americans near The Dalles whom they describe as “great gamblers.” The games, says Wilson Wewa, senior citizens representative with the Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs, included flat, carved bone sticks notched with lines and dots that were tossed in a basket like dice; all manner of athletics, from races to a version of lacrosse; the still-much played “stick game”; and, later, after the 52-card deck arrived with more settlers, a three-card game called Geegeewy. Some games lasted for days. Wagers could include anything from shells and smoked meats to slaves.

First Gamers

Arguably as important as sweat lodges and powwows, hand game (also called “bone game” or “stick game”) was and still is a cornerstone of Native American culture in the West, according to Jackie Peterson, a professor emerita at Washington State University-Vancouver. To play, two teams pile their bets (anything from food and blankets to weapons and cash) and sit facing each other. Each side has two pairs of bones, one marked with a black stripe, one unmarked. After hiding the bones beneath a blanket, one team presents them in closed fists to the other, whose pointer tries to signal which hand holds the unmarked bones. Bluffing, feinting, and frenzied guessing mingle with singing and chanting for a cacophonous roar. Single games often turn into all-night parties.

Gambling though it is, hand game at its core is more about wealth redistribution. In fact, when a missionary visited the Klallam tribe near Puget Sound in 1859, he was horrified to learn that generosity, not greed, drove the players. “The Indian who was worth hundreds in the morning thus beggars himself before night,” he wrote; the person who gives up the most “being considered the greatest man.” Indeed, an Indian origin story tells that when animals finally got tired of humans shedding blood over hunting lands, they invented hand game for them. The winner, the animals declared, could use the other tribe’s territory to hunt for the year. The game greased diplomatic wheels, eased tensions, and placated calls for violence.

Rusty Farmer, president of the hand game tournament Battle of the Nations—which can draw more than 7,000 people—says the pursuit still brings Native Americans together all over North America. “When you have reservations where 85 percent of the people are under the poverty line and 83 percent [are] unemployed, this game can be an amazing spiritual force.” —MP

1852

Illegal gambling rears its head in Stumptown. Upon the election of its third mayor, Simon B. Marye, the Oregonian describes Portland as being “infested with several professed blacklegs … swindling persons who can be induced to risk money upon the turn of a card.” The paper suggests that a few days “in the block house [jail] on bread and water would … purge our city from these bejeweled worthless.”

1903

The Portland Municipal Association’s membership forms, eventually swelling to more than 2,000—all committed to eliminating the scourge of open gambling and slot machines.

1905

Only months before the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition is to pack Portland with 1.6 million eager visitors, a grand jury indicts Mayor George H. Williams for not cracking down on gambling. Reformers worry that gambling houses are not “the best advertisement in the world for exposition visitors,” according to the Portland Telegram.

1911

Lambasting Portland’s government for having “practically licensed gambling and prostitution,” McClure’s Magazine calls the city a “popular headquarters for all the vicious characters in the Pacific Northwest.”

1912

Governor Oswald West finally cracks the whip on local police enforcement of anti-drinking and gambling ordinances, drawing the ire of former Multnomah County Sheriff William A. Storey, who runs a recall campaign against him. Storey assures voters that no vice interests are behind the recall effort. Skeptics abound.

1920s

In response to the brutal turf wars over the control of gambling, opium smuggling, and prostitution in Portland’s Chinatown, powerful Chinese merchants and city authorities establish the Chinese Peace Society to stop future violence. It still exists today as the Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association. Wielding sledge-hammers, axes, and 59 search warrants, District Attorney Stanley Myers raids Chinatown’s illegal lottery and gambling parlors.

In Chinatown

The Chinese lottery reigned in Portland long before its American analog, keno. Run by powerful companies with the backing of tongs—Chinese social clubs whose allied gangs’ turf wars often bloodied city streets—the lottery was fed by immigrants hoping for New World riches.

Bruce Wong’s eyes sparkle when he recalls this rough-and-tumble past. His grandfather (owner of Chinatown’s iconic Hung Far Low restaurant) ran a gambling parlor in the 1930s and ’40s out of his dry-goods store on NW Fourth Avenue and Flanders Street—tucked away behind a steel door in the back. Its existence was not a well-kept secret, but the police usually turned a blind eye, Wong says, until they were called, often by a disgruntled loser exacting revenge for lost wagers. As a result, lottery companies maintained elaborate records to catch cheaters and resolve disputes.

The system was simple: players chose 10 or 20 Chinese characters from a grid of 80 and then placed bets—anywhere from 10 cents to $2. (Instead of randomly selecting numbers, players often spelled out wishes or meaningful phrases with their picks: “I will find a good wife” or “I will strike it rich.”) Wong’s wife, Gloria, worked as a lottery runner, carrying winning tickets to gambling rooms twice a day.

Gaming rooms typically raked in around 5 percent of all bets placed and additional 5 percent of all winnings. But Portland voters plugged the piggy bank in 1949 by electing Mayor Dorothy “No Sin” Lee, who quickly shut down lottery operations for good. Wong, now 79 and a retired forensic engineer, says he’s grateful to Lee on behalf of the whole Chinese community. “It was one of the best things that happened to us,” he says. “We were making good money. Why would I want to go to school?” —MP

1920s

Portland vice squad reports payoffs of $50,000 per month in the city’s 40 “gambling places.”

1931

Oregon legalizes its first form of gambling: pari-mutuel racetrack betting on horses and dogs. Fifteen years later, Portland Meadows opens as the first thoroughbred track in the nation to have nighttime racing.

1937

“Big Jim” Elkins arrives in Portland after serving five years in the Arizona State Penitentiary for shooting a cop during a botched robbery. A small-time pimp and drug dealer, he will eventually become one of Portland’s most powerful crime bosses. His racket of choice? Pinball.

Bumper Crop

Pinball, today, may be a harmless barroom pastime (and a brilliant theme for a late-’60s rock opera), but in ’30s-era Portland, it was an “epidemic” sweeping the city and, in the eyes of some, a dangerous gateway to youth gambling. In those days, many machines were like slot machines, paying out cash and other redeemable prizes. Reformers saw no distinction between pinball and gambling, claiming pinball was a game of pure luck, not skill. The city, a 1936 letter to the Oregonian chided, should not condone the stripping of nickels “from the credulous, the optimistic, the perennially hopeful.”

The law eventually agreed. In January 1937, Multnomah County Circuit Court Judge James W. Crawford banned the machines, branding them as lottery games. “The element of chance predominates in the play of these games,” he declared, modestly acknowledging “the small element of skill” involved. Portland continued to rake in $120,000 annually on license fees for “amusement only” pinball machines until 1951, when Mayor Dorothy “No Sin” Lee declared even such chaste machines illegal. (After years of injunctions and appeals by operators and license-fee-coveting city commissioners, the state Supreme Court upheld the ban in 1954.) Lamenting the many small businesses this ruling would kill, one restaurateur could only shake his head: “Portland is getting to be a city that’s dead.”

Stumptown began rising from that ominous grave when the ban was lifted in 1976. Today our city is home to 415 machines and counting, according to the Portland Pinball Map (portlandpinballmap.com), which receives more than 2,000 hits a day. Scott Wainstock, a co-founder of the website, says luck is only a small part of the game: “It’s incredibly hard, knowing where to shoot the ball, how to keep it up. You’re battling against gravity.” —MP

1940s

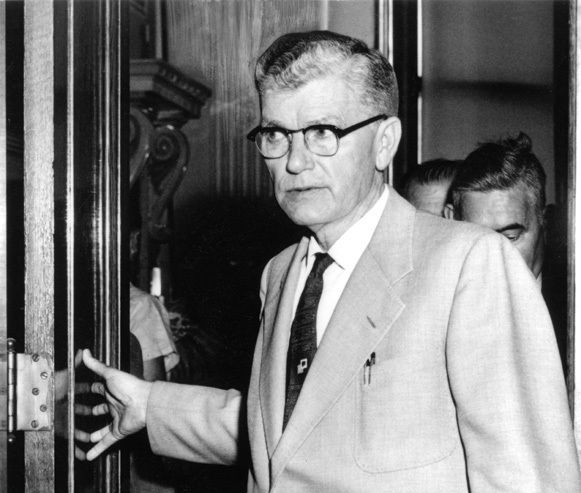

Image: Historic Photoarchives.com

Crime boss Al Winter becomes the undisputed king of all gambling operations in Portland. According to crime writer Phil Stanford, in a scene worthy of The Sopranos, when two small-time crooks try to move in on the action Winter warns them, “The problem is, you didn’t get my permission. Now I want 50 percent of everything you got, and if you do it again, we’ll break your hands.”

1948

A high-profile downtown murder inspires two major reports on vice in the Rose City—damning testaments to the corruption of Mayor Earl Riley. Outraged voters send Riley packing in the next election.

1949

Dorothy “No Sin” Lee becomes Portland’s first female mayor and launches an all-out war on vice. Within the next few years, Lee outlaws slots and gambling in private clubs—including pinball machines, deemed a dangerous “gateway” to youth gambling.

1950

Feeling the cold political winds, crime boss Winter moves his operations from Portland to Las Vegas, where he becomes a partner in the new Sahara Casino.

1951

State police raid 100 Clackamas County night spots suspected of illegal gambling on a tip from a not-so-anonymous Jim Elkins. He quickly fills the vacuum left by Winter.

1952

Elkins pays new mayor Fred Peter-son $100,000 to appoint James “Diamond Jim” Purcell as chief of police. Purcell himself gets another $500 a month for turning a blind eye to Gypsies living illegally on W Burnside Street. Two years later, Elkins helps install William Langley, a gullible investor in one of Elkins’s gambling joints, as district attorney.

1954

The Pinball Wars heat up when Elkins’s goons loot clubs that use competitor pinball machines. The following year Elkins grabs the reins of the Coin Machine Men of Oregon, a powerful, Teamster-backed union for pinball and coin machine operators. Meanwhile, denying operators’ appeals, the state Supreme Court declares Portland’s law against pinball machines constitutional.

1956

Oregonian investigative reporters Wallace Turner and William Lambert pull the covers off illegal gambling and political corruption in Portland, winning a Pulitzer in the process. (Their source is none other than a disgruntled Jim Elkins.) The landmark series of articles marks the end of city government control by the Teamsters and opens the floodgates for criminal prosecution of vice in Portland.

1957

As chief counsel to the Senate Rackets Committee, Bobby Kennedy hauls local officials—including newly elected Mayor Terry Schrunk—to Washington, DC, for hearings televised on prime-time TV, with Elkins playing star witness. Infuriated by the evasiveness and flat-out lies of the assembled suspects, South Dakota Senator Karl Mundt pulls no punches: “It is embarrassing to think of the people of Portland, Oregon, with a mayor who flunks the lie detector test and a district attorney who hides behind the Fifth Amendment. If I lived there, I would suggest they pull the flags down at half mast in public shame.”

1960s

Portland gamblers refuse to fold. Grand juries hand down 115 indictments to 41 suspects, but the city government’s corruption keeps the games going. Elkins’s career as a fixer ends with a whimper when he is arrested for possession of narcotics and stolen property. In 1968, he is found dead.

1972

Public polling shows 58 percent of Oregonians favor a lottery to raise money for government operations. The Oregonian calls it an “inefficient tax which is very likely to hit poor people hard.” The Legislature refuses to even allow the public the chance to vote on it.

1984

Voters take matters into their own hands: in the midst of a deep recession, they approve ballot measures 4 and 5 by a nearly 2–1 margin, creating the Oregon Lottery to encourage economic development.

1985

Pennies finally have another use with the introduction of the first Scratch-It game, called Pot of Gold.

1988

“Money Game,” the first Oregon Lottery television game show, debuts.

1988

Lotto*America (later Powerball) arrives in Oregon when the state becomes one of the first seven members of the Multi-State Lottery Association (MUSL).

1991

The Oregon Lottery takes over the roughly 10,000 illegal video slot and poker machines—known as the “gray machines”—and regulates and taxes them. The earnings now account for 80 percent of the Lottery proceeds to public education, economic development, and natural resources.

1992

On the heels of the 1987 US Supreme Court decision allowing gaming on tribal lands, Oregon’s first Native American bingo hall opens its doors in Canyonville. Two years later, the Cow Creek Band of Umpqua Indians upgrades the hall to the Seven Feathers Casino Resort. By 2010, the state will boast nine Indian casinos.

1994

Video Lottery retailers sigh with relief when the state Supreme Court confirms their exemption from Oregon’s casino prohibition. By 2010, there will be 2,366 bars and restaurants with 12,333 Video Lottery machines in Oregon.

1995

Disbanded by the federal government in 1954 but officially re-recognized in 1983, the Grand Ronde join the Indian gaming party, building Spirit Mountain Casino. It becomes the state’s most lucrative casino.

1995

Governor John Kitzhaber appoints a task force on the effects of gambling in Oregon. The results are inconclusive but hint at a growing concern: gambling addiction. For the next decade, the number of Oregon addicts receiving treatment will increase by 25 percent every two years.

1997

The Lottery becomes an even more fundamental part of Oregon’s economy as the state uses gambling revenues to back bonds for public school projects.

1998

Gambling goes green when voters dedicate 15 percent of Lottery proceeds to fund state parks, watersheds, and salmon restoration.

2006

More than 1,700 Oregon gamblers enroll in publicly funded gambling addiction treatment centers this year. Their average debt? $23,331.

2007

After eight years of battles with the NFL, NBA, and NCAA (the last organization even blocking postseason tournament games in the Rose Garden), the Oregon Lottery pulls the plug on its popular Sports Action and Scoreboard games, which allowed players to bet on the results of sporting events.

2008

Despite the deepening recession, Oregon hits an all-time high in gambling revenues—$622.5 million, or 9 percent of its annual general fund budget.

2009

The recession and the new Oregon Indoor Clean Air Act’s smoking ban are blamed for sending state gambling revenue spiraling downward by 15.2 percent from 2008.

2010

Oregon voters draw the line on gaming, crushing a proposal for the state’s first full-blown non-Indian casino, in Wood Village, by 36 percent. Meantime, the Warm Springs tribes anxiously await Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar’s decision on their proposed casino in the Columbia River Gorge at Cascade Locks. With the Grand Ronde tribes fearing competition for Spirit Mountain Casino (and arguing that their original treaty lands extend all the way to Cascade Locks) and the Warm Springs tribes threatening to build on a far more visible site at Hood River should they be turned down, political muscling and intertribal snarking abound. If Salazar says yes to the project before incoming Governor John Kitzhaber’s inauguration, outgoing Governor Ted Kulongoski will face a choice: gentlemanly guv-to-guv deference to Kitz’s staunch opposition to the casino (punctuated by the Grand Ronde’s $50,000 gift to his campaign) or make good on his longstanding promise to boost the tribes and Cascade Locks with jobs—while echoing ancient origins of Oregon’s games of chance.

Place your bets!