Manila Mata Hari

The party at Ana Fey’s nightclub starts to get wild. A Japanese civilian, surrounded by cronies at a corner table, all drunk on cocktails and a self-confidence born of conquering half the Pacific, decides he wants special attention.

He beckons the club’s Italian singer: the tall brunette with the sultry voice, high heels, and shimmering gown, who’s been entertaining Japan’s forces with romantic songs in English from Ana Fey’s tiny, spotlit stage. The patron wants the singer to bring him ice for his drinks personally. The singer demurs. The patron insists—even grasps the woman’s backside. She slaps him across the face.

No one did that to one of Emperor Hirohito’s subjects in occupied Manila. The men take the singer into the club’s back room and beat her; the orchestra plays more loudly to cover her cries. But even as the drunken soldiers teach the nightclub girl “a lesson,” their blows fail to dislodge wartime’s most valuable commodity: the truth.

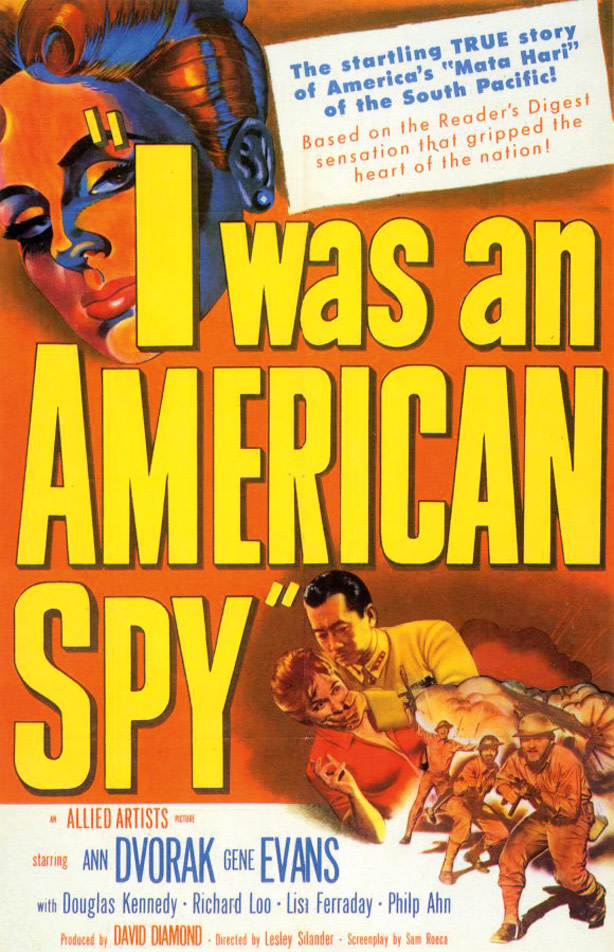

The singer wasn’t Italian, but American, from a small city across the Pacific Ocean. And she was no mere club beauty, but a budding spy, working to eclipse the Rising Sun. Her real name was Claire Phillips. Her code name was High Pockets—in honor of secret messages she stashed in her bra. She was fighting in the fierce shadow-contest over a city that played a key role in the Pacific theater’s brutal chess match. So the beating Phillips suffered that night—not her worst ordeal, by a long shot—was just part of the job. Years later, after the war, Hollywood made a movie about this chanteuse/agent. In I Was an American Spy, the beautiful (but fading) star Ann Dvorak embodied Claire Phillips. Another character, a fellow singer, told her: “You’ve had a good time while it lasted, but there’s a war on.”

This year brings the 70th anniversary of America’s plunge into World War II. I Was an American Spy came out in 1951, at a moment when Phillips, an obscure—even troubled—woman from Portland, tasted national celebrity. Today, few people remember the only Oregon woman ever awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom. Phillips lived and died in worlds nearly lost to living memory: the war, the extraordinary acts of bravery it demanded, and America’s postwar zenith.

A small local group of historians and admirers believe Phillips’s candle deserves rekindling. “This woman was rock-star famous,” says Sig Unander, a local history buff, writer, and filmmaker. “And that makes it more poignant that she’s been forgotten.” Unander is at work on a book and documentary about Phillips, and hopes to inspire a memorial to this forgotten local heroine. The World War II generation has received many accolades. But few Portlanders’ service could outstrip the drama—or pain—of Phillips’s saga.

She was born in Michigan in 1907, and arrived in Portland as a young child when her stepfather, a marine engineer, came to work in a shipyard. By her teens, a natural wanderlust emerged. In a Franklin High School photo, young Claire looks out from beneath a tangle of youthful curls with a half-smile and a subtly mischievous gleam in her eye. She soon ran away to join a travelling circus, selling tickets to a snake charmer’s show. In later years, she learned on the job as a singer and dancer in Northwest clubs. Eventually, Claire joined a musical stock company touring Far East metropolises like Hong Kong and Manila.

The Philippines was then America’s largest colony. Manila, a vibrant, garden-filled city, was one of the most popular Asian destinations for westerners—and the US military’s largest Pacific stronghold after Honolulu. As Asia’s busiest port, Manila blended native Filipinos, Americans, Europeans, and Chinese. Claire met and married a Filipino man. When the marriage turned sour, she fled back to Portland with their adopted daughter, Dian.

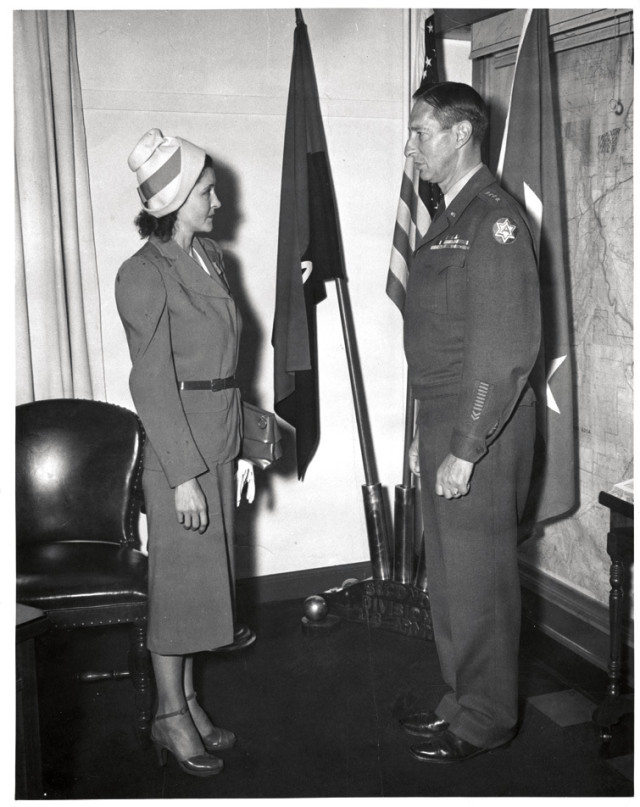

Claire Phillips received the Medal of Freedom in 1948.

It was 1941. The Nazis ruled much of Europe. Japan’s conquest of China and new alliance with Germany and Italy meant citizens on both sides of the Pacific could see war coming. Claire was … bored. That summer, she and Dian boarded a ship back to Manila. Mother and child arrived just three months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbor.

“Call it restlessness, fate, wanderlust or the whirligig of chance,” she wrote in her 1947 memoir, Manila Espionage. “Maybe I was not fond of sitting in the wings.” In other words, she was impulsive and addicted to drama. These qualities didn’t make her the greatest daughter, mother, or solid citizen. But they would make her an excellent spy.

In the simmering tension before Pearl Harbor, Claire sang “under a soft cascade of shifting pastel lights” at Manila clubs. One night, she locked eyes with an American soldier, John Phillips. She sang to him as if they were the only people in the house. “The soldier looked at me in the manner that a woman longs to be gazed at,” she later wrote, “by the right man.” A quick-strike courtship ensued: all dancing and walks on Manila’s palm tree–lined beaches, willfully ignoring a darkening world.

On Dec. 8, 1941, Japan invaded the Philippines, overwhelming American forces. Claire hastily married John, then fled with Dian into the mountains. Among thousands of refugees, they survived on a diet of wild game, snakes, and monkeys. In this chaotic exile, Claire met another American soldier, John Boone, who had evaded capture. Boone planned to assemble a guerrilla army to resist Japanese occupation. He also was a former theatrical agent—and he offered her the role of a lifetime.

“There are hundreds of Filipino and American soldiers lost and starving, but still with a burning yen to fight Japs,” Claire recalled Boone telling her. “If I had a good contact in Manila to smuggle food, clothes, and medicine up here, it would work.” She hesitated—but soon learned that her new husband had been captured (and, she would later learn, killed). So now the war was personal.

The Tsubaki Club enjoyed a view of Manila’s docks, which, in 1943, teemed with Japanese naval and merchant marine ships. It was the hot new place, opened by the Italian-born Filipino gal known as Madam Tsubaki, who used to sing at Ana Fey’s. Tsubaki also boasted Ana Fey’s former head dancer, Fely Corcuera, who was fluent in Japanese. (Meanwhile, an affluent Chinese businessman, along with Madam Tsubaki’s pawned diamond rings and watch, supplied the club’s initial stake.) Corcuera dressed in a kimono and regaled Imperial Navy boys with traditional Japanese songs. Afterward the floor show—with dancers wearing little more than gold satin G-strings, coconut shells, and headdresses fashioned with turkey feathers—went deep into the night.

And then there was Madam Tsubaki herself.

Six decades later, the writer Hampton Sides described the Tsubaki Club’s proprietress in his book Ghost Soldiers: “She … dressed in a white evening gown with a plunging neckline and a slit halfway up her thigh …. Her olive skin would glitter with jewels.” Each night, Madam Tsubaki greeted patrons and escorted them, as Sides tells it, “through the cream-colored bar, past the dancing stage with its curtains of lavender satin, to the rattan settees along the back wall.” There, Madam Tsubaki cuddled up with her club’s most prominent guests and asked questions in a pidgin of Spanish, Japanese, Tagalog, and English: When do you leave Manila? Where will you go next?

A saucy dance revue. Doting waitresses. Cocktails. What war-weary sailor wouldn’t relax and let a few details slip?

The Hollywood version of her story.

Before dawn, Phillips scrawled those details in a note, which she slipped to a Filipino runner in the alley behind the club. The runner vanished into the mountains to rendezvous with Boone’s guerrillas. A shortwave transmission relayed news to General Douglas MacArthur in Australia or New Guinea. And then, often enough, the Tsubaki Club’s guests met unpleasant fates. Phillips later claimed that one of her tips led to the annihilation of an entire Japanese submarine squadron.

Meanwhile, Phillips spent her days—and her club’s profits—on another mission: smuggling food, notes, and medicine to American POWs held at the Cabanatuan prison camp outside Manila. For these men—sick, starving, prone to maltreatment and random execution—she was both a practical and emotional tether to the world. One imprisoned soldier wrote to Phillips: “You’ve done more for the boys’ morale in here than you’ll ever know … You deserve more gold medals than all of us.”

For her part, Phillips always signed her dispatches: “Yours in war, High Pockets.”

Eventually, the Japanese caught Phillips. Interrogators shot water into her mouth from a hose. “Guards held my head so that I could not move,” she wrote. “I held my breath. A Nip noticed this and hit me in the abdomen. I gulped the water down … drowning on dry land … then oblivion.” Captors burned her skin with cigars until she awakened. By the time American troops liberated her prison on February 10, 1945, she had lost 55 pounds.

On a rainy Tuesday in 2010, Sig Unander walked up to a green-gray midcentury cottage with chipping paint and a crop of weeds, just east of Murray Boulevard in Beaverton.

No one answered the doorbell. This had been Phillips’s postwar home, a reward for her Manila service. Today the place feels more like a monument to oblivion than heroism.

After the war, High Pockets seemed to rebound well. First came a Reader’s Digest feature. Then, at MacArthur’s recommendation, a Medal of Freedom—the nation’s highest civilian honor. Her published memoir led to the movie. (Phillips was arguably prettier than Dvorak, but the casting was apt: Dvorak has been called “Hollywood’s forgotten rebel.”) Phillips went to Hollywood to advise the production and hobnob with stars like Dvorak, whom she’d helped choose as her cinematic double.

Soon after, Phillips was guest of honor on NBC’s top-rated radio show This Is Your Life. Back in Portland, more down-home honors flowed. A Beaverton developer provided the house. A local Packard dealership gave her a new car. Lewis & Clark College pled-ged free tuition for Dian. Hundreds gathered before a makeshift stage in the driveway to watch the lady spy take the keys to her new home.

But her life descended quickly. Working at Lipman’s department store wasn’t her idea of adventure. Within three years she divorced a third husband. Dian dropped out of high school, never accepting the scholarship. In the late ’50s, Phillips also faced a public comeuppance when she unsuccessfully sued the US government for $146,850 in compensation. Support came from Boone and Oregon Senator Wayne Morse, but she was rigorously cross-examined and chastised for her inability to document what she spent in Manila. “Much of her story was greatly exaggerated and at times almost fanciful,” the US Claims Court decision read. Phillips received just $1,349, even though others with little documentation received large sums.

The Hollywood version of her story cast Ann Dvorak as the sassy Franklin High graduate.

Phillips often woke up screaming at night. She drank. She’d die within a decade of meningitis. “She never was very well after she got home and never very happy,” her mother wrote to a relative afterward.

In recent decades America has celebrated the “Greatest Generation,” perhaps at the expense of the individuality—in some cases, the essential strangeness—of its members. Claire Phillips’s wartime intrigue and lost love are ripe for rediscovery. A signed copy of her book currently fetches up to $200 on Amazon, and one can almost imagine Angelina Jolie or Cate Blanchett fighting over the role. Yet Phillips is most compelling not as a faultless hero but as a human beset by imperfections: the sultry singer with the meteoric fate, the loose cannon who met her historical moment, then watched it slip away.

“This woman relished the lime-light, loved to take chances, and was an adventurer,” Unander said as he departed the rain-soaked old Beaverton house. “She’s not going to be happy playing mahjong with the girls on a Wednesday evening. One of her relatives said that Claire never slept with the lights off. She’d lived a dozen lifetimes in a few years.”