Little Big Nurse

Soon after longtime Portland actress Gretchen Corbett learned she would play the notorious Nurse Ratched in Portland Center Stage’s upcoming version of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, she began to worry. Not about the role, really. During her long career she’s played everything from Beth Davenport (Jim Rockford’s lawyer and occasional love interest) in The Rockford Files to Joan of Arc in the New York Shakespeare Festival. It was friends’ reactions that disturbed her. She performs a comic double take as she recalls how several were a little too quick to say, “That’s a really good part for you.”

Being a natural for Nurse Ratched can cut two ways. She’s the crucial gear that keeps the brutal machinery in the story’s setting—a mental hospital—humming; she seems to squeeze the lifeblood out of anything human; and she is the archenemy of the story’s protagonist, the charmingly roguish Randle McMurphy. Yet, Ratched may be novelist Ken Kesey’s greatest invention, simply because she’s such an original and singular character in American literature: a villainess who operates within the system and controls everyone, including the men—maybe especially the men—around her.

In the novel, McMurphy describes the nurse as “big as a barn.” Corbett is small. She can look positively elfin when her smile is in full beam. But like Corbett’s friends, Rose Riordan, who will direct PCS’s production, also saw Corbett as an excellent fit. “I thought about her a lot while reading the play and the book,” Riordan says. “What Gretchen will bring to the role is psychological power. It’s not a physical intimidation but a mental one.”

When we sat down to talk, Corbett had barely begun her research. She hadn’t watched Milos Forman’s film version, winner of five Academy Awards, including one for Louise Fletcher as Nurse Ratched. She hadn’t seen Dale Wasserman’s stage adaptation (the version PCS will present, which had Broadway runs in 1964 with Kirk Douglas as McMurphy and 2001 with Gary Sinise). And she claimed scant acquaintance with the novel, though in the course of conversation she references some obscure bits of it. But what she had already begun was her “advocacy” of the character—finding sympathy with Nurse Ratched; seeing the world as she sees it. “From the inside,” Corbett says, “no one feels like the quintessentially evil human being. And anyway, I don’t know how to play that person.”

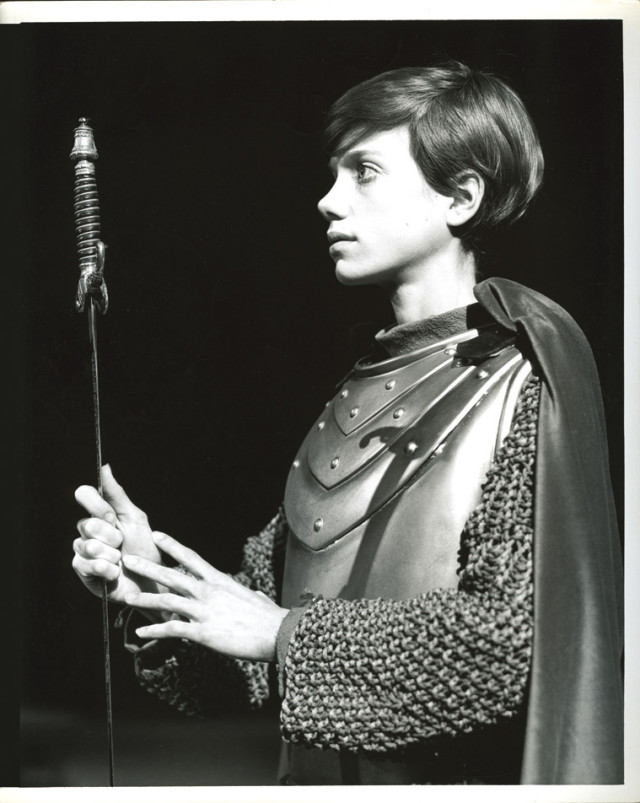

Corbett plays Joan of Arc in an American Theatre Company production, circa 1970.

Finding the good inside Ratched won’t be easy. Because of the popularity of the movie—and of Kesey’s novel, a cult masterpiece of the ’60s—the battle between Ratched and McMurphy has become mythic. McMurphy, who has connived his way out of a stretch at the state work farm by pretending he’s insane, is a new patient in the ward. He’s rambunctious and a manipulator, as Nurse Ratched immediately observes, and he presents a serious challenge to the system she’s built over her long service to the hospital. The novel is built on their confrontation as told by Chief Bromden—a.k.a. Chief Broom—who has decided that playing deaf, dumb, and dim is his best defense. The constant observer, pushing his broom around the edges of the action, the chief concocts a paranoid cosmology for the hospital (with Nurse Ratched at the helm). Or as Kesey writes through Bromden: “I see her sit in the center of this web of wires like a watchful robot, tend to her network with mechanical insect skill, know every second which wire runs where and just what current to send for the results she wants.”

Director Riordan describes Nurse Ratched’s ultimate power over her charges in the hospital in a different way: “She can sign something and you’ll have your brain operated on.” Yet, before this vision of Pure Evil swamps the character of Ratched, Riordan offers a lifeline not dissimilar to Corbett’s advocacy. “Her femininity is of no consequence to her,” Riordan says. “She’s trying to accomplish something in a man’s world, and she has to control things at all costs.”

Ratched’s management fetish, Corbett suggests, grows from experience. “It’s important for the patients to believe that they have autonomy, sure, but often she knows better the path they need to be ushered toward,” says Corbett. “She’s seen it all.” Corbett notes her own willingness—“not a desire but a willingness,” she cautions—to be “disliked in doing what I view as right.”

“I think I share that with Nurse Ratched,” she says, recalling her own experiences as the artistic director of the Haven Project, where she taught theater skills to underserved kids in Portland. “Sometimes,” she says, bluntly, “shame works well.”

Over the conversation, Corbett searched for literary and film parallels to Ratched, including parts she’s already played. In an episode of the television series Wonder Woman, Corbett portrayed a villain, giving her a little goosestep and German accent, but that’s not quite it.

?She’s played Joan of Arc three times—in George Bernard Shaw’s version, Shakespeare’s depiction in Henry VI, and a rock-opera version. She may not have been a villain (unless you were English), but Joan did command a nation of men.

Imagining how she will embody the woman Chief Broom dubs “the Big Nurse,” Corbett recalls becoming Joan for a Shakespeare in the Park production in New York and what it felt like to get carried on the shoulders of the soldiers, wearing the armor, brandishing the sword. After one performance, a woman came up to her, looked her up and down, and said, “Oh my God, you’re tiny!”

Corbett shrugs at the memory. “I can get big on stage.”