Brainstorm

“Being crazy is the seed for other ideas…”

FROM THE WHEELS TURNING BENEATH OUR VEHICLES TO THE GADGETS CONNECTING US to the world, every day—indeed, every second—we enjoy the fruits and hard labor of human innovation. We often shine a spotlight on discovery, occasionally on the discoverer. But all too seldom do we turn on a penlight and search for the finer-grained influences, inspirations, and serendipity—not to mention the sprouts of insanity, small and large—that breed a profound breakthrough.

Six months ago Portland Monthly and the Oregon Museum of Science and Industry (OMSI) joined forces for just such an exploration. We queried our readers and experts in numerous fields to put together a list of 130 leading Oregon innovators, then assembled a panel of five community leaders with a wide-angle view of the future: Skip Rung, executive director of Oregon Nanoscience and Microtechnologies Institute; Erin Flynn, vice president for strategic partnerships for Portland State University; Tom Manley, president of the Pacific Northwest College of Art; Allen Alley, cofounder of Pixelworks; and Nancy Steuber, president of OMSI. Together with the panel, we narrowed the list to 12 game changers from a spectrum of disciplines who, in large ways and small, are shaping the horizon. And then we started asking questions—about what they do and, more important, how they do it.

Throughout October you can discover the answers: in a series of Monday-evening conversations at the Bagdad Theater (see schedule below) and an interactive display at OMSI, as well as in the pages that follow. We hope you will be inspired to discover new creative paths in your own life. —Randy Gragg

I look at a community and say, “What’s the force?”

Image: Carlin Sundell

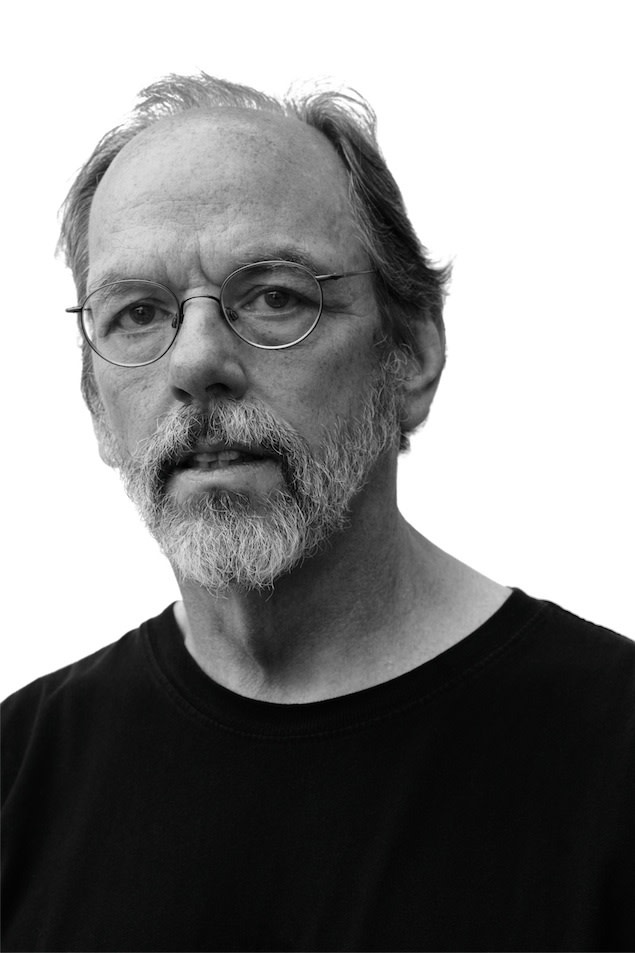

Ward Cunningham, 62

Principal engineer, AboutUs

WARD CUNNINGHAM relishes personal tendencies most people would hide as flaws. He has a terrible memory. He was a slow reader. “Writing,” he says, “kind of sucks.” But each shortcoming has become a motivation in his longer-term game of revolutionizing computer programming. The most important of all was his aversion to a practice most engineers crave—planning.

“Throw away the plan,” he says. “The plan will be wrong. Planning impedes learning, because with most computer projects, about halfway through, you realize what you should have done. So let’s just not be stupid. Let’s expect to learn.

“I’m actually a lousy learner,” he adds. “But I just didn’t stop.”

Cunningham’s make-it-up-as-you-go ethos has produced some of the most important breakthroughs in computing in the past two decades, ranging from “design patterns” (a sort of “good habits” method of programming methodology inspired by Christopher Alexander’s architectural treatise, A Pattern Language) to the wiki, the foundation for such participatory databases as Wikipedia. Now the principal engineer for AboutUs.org, the world’s largest wiki for websites, Cunningham also has a new side gig as the first “Nike Open Data Fellow.” He splits his time between the Beaverton campus and Wieden & Kennedy’s Portland Incubator Experiment (PIE). The agenda: taking Nike’s growing open-source database of sustainable materials and practices and making it participatory. “It’s daring,” he says of the new job, “in the sense that they don’t have a clear idea of what I’m going to give them.”

In the modest home he’s shared with his wife and two sons in Garden Home since arriving to work as principal engineer at Tektronix in the late ’70s, Cunningham’s many computers are actually outnumbered by inventions: a home temperature and humidity monitoring system and a range of kinetic sculptures he can set into motion with his iPhone, what he calls “one-day projects,” crudely built from hobby-shop parts but often driven by the latest in web technologies. Variously describing them as “ways of seeing” or like the exercises of “playing piano,” they are important to his thinking because they are not his job.

“I think of myself as an artist when I want to free myself from the obligation to deliver something,” he says. “I think artists are pretty good at separating what they want from what the customer wants. And with that is mastery. Sometimes you master skills so that you can apply them in a fresh way. I’m always working on mastery of computers. The challenge is to will them into something worth doing. And ‘worth doing’ is artistry.” —Randy Gragg

The waves come in and show you who’s boss.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Annette von Jouanne, 42

Electrical engineer and professor, Oregon State University

SOME LITTLE GIRLS play “house.” Annette von Jouanne, at age 8, played “take it apart.” She plunged into her parents’ broken alarm clock, discovered a bad contact, cleaned off the oxidation, and put it, ticking, back on the shelf. She regularly fixed her Commodore 64 and even dismantled and reassembled the family TV in fevered electrical forays timed to her parents’ absence just to see how it worked. From age 10 on, she devoured her brothers’ college engineering textbooks to help guide her home investigations.

With similar intensity, von Jouanne learned to swim, first in pools, then in oceans, and now every day in the swim flumes she designed for her home’s basement. During regular family swim trips to the coast, the Oregon State University professor’s mechanical aptitude, physical passion, and religious conviction (she cites Psalms 93:4 as an enduring inspiration: “Mightier than the breakers of the Sea, the lord on high is mighty”) swirled together to generate an idea that would transform her into a pioneer for the then nonexistent field of wave energy. “Boy, when you’re riding those swells and getting tumbled, that really helps you gain respect for the raw energy in those waves,” she says “I’d come back each time thinking: if only we could harness that energy.”

So in 1998, at a time when wave energy was, at best, considered far-fetched, von Jouanne started writing grants and developing designs. “She was doing the really hard work of a lot of testing and modeling,” says Ted Brekken, an assistant professor of electrical engineering at OSU. “No one else was doing it.”

Today, the lab von Jouanne codirects, Wallace Energy Systems and Renewables Facility (WESRF, or “We Surf”), has lured some of the world’s leading wave researchers to Oregon and produced 12 successful prototypes and counting. She has helped land the National Marine Renewable Energy Center and a cluster of wave-energy start-ups at and around OSU. One collaborator, Columbia Power Technologies, is testing a one-seventh scale prototype in the Puget Sound. By von Jouanne’s calculation, wave energy could contribute 10 percent of Oregon’s energy by 2025.

“We are a world leader in terms of wave energy research,” says Solomon Yim, assistant professor of structural and ocean engineering at OSU and former director of the O. H. Hinsdale Wave Research Laboratory. “Annette was the person who built that up and brought it to fruition. She is a missionary for wave energy.” —Aaron Scott

You witness. You walk a mile in someone else’s shoes.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Eric Dishman, 43

Director of health innovationand policy, Intel

MOST 16-YEAR-OLDS—even a computer geek like Eric Dishman—would consider caring full-time for an Alzheimer’s-afflicted grandmother a form of social death. For Dishman it became the birth of a career. “There was no technology, there were no services, people barely understood what Alzheimer’s was,” he recalls. “I thought, ‘There’s gotta be a better way to help families cope.’” As Intel’s director of health innovation and policy, Dishman now develops technologies and fights legislative battles to improve health care and quality of life for all seniors.

Dishman’s program is ambitious: move 50 percent of all health care to the home; allow doctors and nurses to provide care electronically and over the phone when needed; and provide incentives to doctors and nurses to make prevention (rather than treatment) the central focus of care. His means are often unconventional. A communications major and tech wunderkind (at age 21, he joined Paul Allen’s Silicon Valley–based think tank, Interval Research, to conceive of how computers would move from the office to our everyday lives) who’s dabbled in anthropology, sociology, rock ’n’ roll, and theater, Dishman often pairs doctors, nurses, and patients with improv actors to imagine new technologies. He argues that in his extensive field observations of the health care system one of the biggest insights he ever gained came by “handing the clipboard to the patient.”

“They start taking notes as the doctor’s talking to them, and guess what The whole thing changes,” he says. “The doctor slows down and starts helping them make sure they’ve got it right.”

Dishman provided expertise in the drafting of the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, helping to add, for instance, key provisions that would allow doctors and nurses to be paid for services provided electronically. His most recent creation, a touch-screen tablet software called Connect, is designed to combat the loneliness and isolation that he’s observed with seniors. Not only does it allow users (and their health care providers) to monitor their well-being on a daily basis through a series of branching questions, it provides a simple-to-use, Facebook-like platform that allows seniors to connect with family and friends.

“Just because you’re absent of an illness or an injury doesn’t mean you’re having a meaningful human experience,” Dishman reflects. “Health is not the absence of pain. It’s the presence of purpose.” —Martin Patail

I’m doing exactly what I want and hoping that people can feel it.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Naomi Pomeroy, 36

Chef/owner, Beast

OVER THE PAST DECADE, Portland chefs have rotated through the buffet line of James Beard Award nominations and wins, national food magazine spreads, and New York Times ink. But no local chef has enjoyed more notoriety than Naomi Pomeroy of the Northeast Portland restaurant Beast. Schooled in cooking by her mother and by humble experiences stirring up dormitory meals for her Lewis & Clark College roomies (with ingredients stolen from the commons), Pomeroy has risen to do “truffle battle” with (and narrowly lose to) Iron Chef Jose Garces and cooked her way to a fourth-place finish on this year’s Top Chef Masters.

But celebrity is only one pursuit. Counting among her inspirations both pioneering chef Alice Waters and Burmese pro-democracy activist Aung San Suu Kyi, Pomeroy reshaped Portland dining into a total, immersive experience. First came Family Supper, the living-room dinner club she founded in 2001 with then-husband Michael Hebb, and most recently Beast, a 24-seat room in which she and her longtime sous-chef, Mika Paredes, cook each course in the centrally open kitchen.

“There’s something powerful in integrity, a general sort of word I use to describe anybody that’s doing something that speaks true to themselves,” she says. “Whether it’s food or an art show, if it’s speaking to the person that’s creating the project, you can tell—if you’re paying attention.”

With a jeweler and thoracic surgeon for a father and grandfather, respectively, Pomeroy is meticulous and driven. “I don’t feel competitive with other chefs,” she says. “I want to beat myself at my own game.” Her greatest influence on how she shapes her dining experiences comes from her single mom’s ritually relaxed style of cooking and eating learned during her time in Lyon, France: simple ingredients served in three casually prepared meals every day, the final arriving at 9 p.m. with just the two of them savoring the food and talking late into the night. “I have a holistic view of the way that a system works,” she says. “It just translates somehow and leaves you with a feeling of being really taken care of.” That Pomeroy/Beast feeling has drawn diners ranging from former Gourmet editor Ruth Reichl to actress Drew Barrymore. A cigarette filter adorns Beast’s back refrigerator: one of many John Malkovich tore off his Marlboro Lights as he smoked between courses on a recent visit.

It’s ok to be wrong, and it’s ok to fail.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Larry Sherman, 46

Head of the Sherman lab at the Oregon National Primate Research Center at OHSU

A FUNNY THING HAPPENED to neuroscientist Larry Sherman on his way to a cure for neurofibromatosis, a tumor-producing genetic disorder. He suddenly found himself on a road to solving the mysteries of multiple sclerosis.

The unlikely turn arose from a failed 2002 experiment. Sherman had genetically altered mice to produce a protein called CD44 that he theorized would produce tumors. Instead, the mice began shaking—a lot. Rather than casting the tumorless rodents aside, Sherman recalls thinking, “This is really cool; let’s figure this out.” Turns out, the protein had prevented the formation of myelin in the mice’s brains and spinal cords—making them look eerily like patients with MS. The shaking mice became part of a successful grant application to the National MS Society and a whole new direction in his research.

Now head of the Sherman Research Center at OHSU’s Oregon National Primate Research Center, Sherman is one of the world’s leading experts on myelinating nerve cells. His work is leading to possibilities for fixing damaged brains, whether ravaged by MS, shaken by chemotherapy, or eroded by simple aging.

The San Diego native’s career-changing nimbleness and skilled eye for putting together puzzle pieces from many disparate experiments in novel and often-surprising ways pervades all of Sherman’s research, indeed, his entire life. Case in point: having played piano by ear since he first banged out a song from a musical at age 4, when he’s stuck on a problem he’ll improvise on the piano for 30 minutes and then go back to the enigma with new clarity. After hearing him play, a colleague suggested he do a talk on the neuroscience of music; instead, he created a concert-lecture that is one of the city’s hottest lecture tickets. He’s even in talks with the Portland Chamber Orchestra about a new project on the nature vs. nurture debate.

“He’s very open to proposing an oddball way of thinking about things,” says David Gutmann, director of the Neurofibromatosis Center at the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and a collaborator with Sherman since he was a post-doc. “As a scientist, it’s very easy to get so enamored with your own ideas that you will continue down the path even when the data suggests another explanation. Larry doesn’t do that.”

For Sherman, curing disease is just a bonus of what really gets him up in the morning: the pure research. “The basic motivation,” he says, “is that we’re doing something that no one’s done before, and we could make a new discovery today.”

—Aaron Scott

If you can’t make someone cry, you’re just not trying hard enough.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Iain Tait, 39

Global interactive executive creative director, Wieden & Kennedy

ON A SOUND STAGE IN LONDON, Iain Tait watches as multiplatinum pop-rock outfit Maroon 5 writes a new song. Behind the band, a giant display board offers a Twitter feed, displaying in real-time the suggestions from thousands of fans watching live over the Internet. For them, the marathon 24-hour songwriting session is a rare chance be a part of the band’s creative process. For Tait, who developed the event for Coca-Cola, it’s the future of advertising.

“There are certain parts of the advertising world where you’re still speaking from the top of the mountain with a big loud message. There’s a place for that. But people expect more now,” says Tait. “They expect a toothpaste to talk back to them if they say the toothpaste sucks.”

Tait is the ad whiz who has helmed Wieden & Kennedy’s digital push for the past year, vaulting the venerable 29-year-old agency to the vanguard of digital advertising. Best known for the interactive 2010 YouTube campaign for Old Spice with the football Adonis Isaiah Mustapha, Tate is now at work on new technologically proffered consumer connections to Coca-Cola Music and Nike Better World.

Scottish-born and raised in Barton-under-Needwood, England, Tait became a lifelong geek when he got his first computer in 1982, a ZX Spectrum, on which he programmed simple games. But it wasn’t until the early 1990s, when he began exchanging mix-tapes with strangers he met online, that he began to grasp the power of digital connectivity. “Everything’s a learning experience,” Tait says. “What’s important is to have an environment and a culture where you can take some calculated risks and be able to try stuff out.”

Indeed, as global interactive executive creative director for a famously free-form ad firm, Tait has the elbow room to do just that. Coming up with new ideas requires indulging his myriad other interests, which on any given day may include video games, psychology, or urban planning. If done right, digital media should not just be aesthetically appealing, he argues, but should actively evoke emotion, like a film: joy, sadness, relief, fear, laughter.

“So much of the art of creativity now is about joining other disparate things,” says Tait. “You need to look really far away from where you intend to get to.” —Martin Patail

I’m trying to… create a vision for what good looks like.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Lorrie Vogel, 46

General manager, Nike Considered Design

WHEN LORRIE VOGEL was a toy designer at Texas Instruments, her boss refused to look at any new product design until she had sketched 100 different versions. She recalls the long nights she spent sleeping in her studio and playing mental games to come up with just one more. “At 10, you’re like, ‘No, none is going to be better than this one,’” she says. “Then, sure enough, around 99, it’s way better than the 10th.”

Such relentless interrogation of the possibilities led Vogel from designing products (everything from toys like Peek-a-Boo Zoo to radio-tracking transmitters injected into roaming pigs) to redesigning the apparel industry as the manager of Nike’s sustainability division, Considered Design. “If you give me a problem,” she says, “I’m going to come up with different systems and processes to solve it.” Early in her current post, for instance, she reduced Nike’s materials consumption 30 percent by redesigning the company’s packaging. The other changes she’s helped pioneer have ranged from World Cup soccer jerseys made from plastic bottles (eight per jersey, to be exact) to open-sourcing Nike’s new recipes for water-based adhesives and recyclable shoe-sole rubber.

As a woman—one of only two to finish her design program at Syracuse University—Vogel is a rarity in the upper ranks of industrial designers. Her father encouraged her fascination with his collection of tools; her mother, with sewing. (Note: Vogel’s sister, Nicole Vogel, is publisher of Portland Monthly.) At the all-girl Catholic high school she attended in Houston, she notes, it was “cool to come to school with scrunchy hair tied up in a rubber band to show people how you’d worked all night long to come up with a good grade.” But she is part of a growing crowd of women leading corporate sustainability initiatives. “Women tend to be more systems thinkers,” she says. “Men might be more on-task.”

These days at Nike, Vogel is more strategist than designer. “A lot of people are creating sustainable products, but the majority are working on things that are less bad,” she says. Her goal is to chart Considered Design’s path “away from consumption to transaction,” so that every product Nike makes can be reclaimed. And that, Vogel says, begins with motivating designers.

“I try to create an environment where people can feel good about coming up with ideas, knowing that they won’t be harshly judged even if they are crazy. Being crazy is the seed for other ideas.” —Randy Gragg

We fool ourselves if we think we’re coming up with any new ideas.

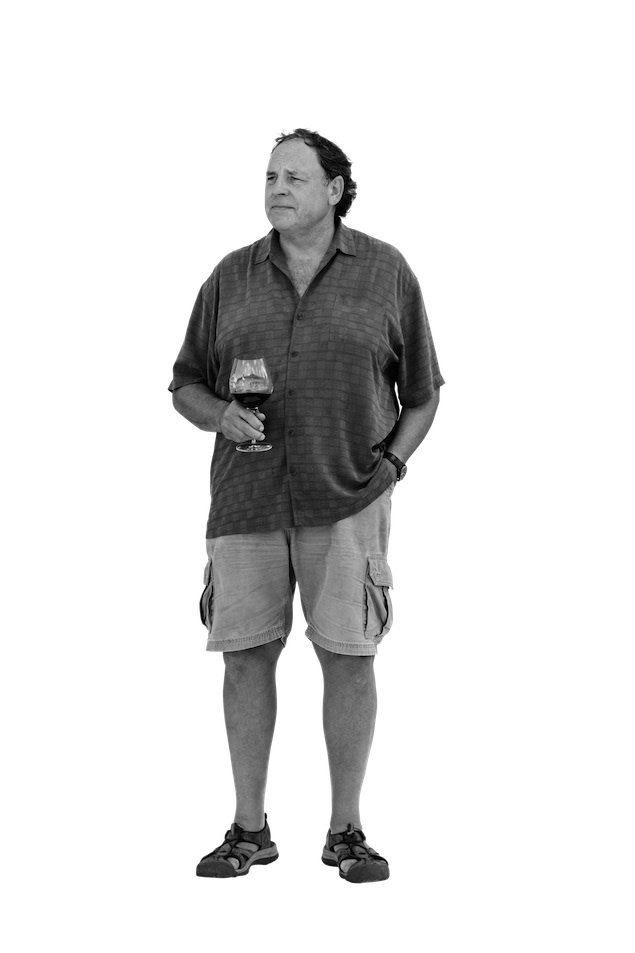

Doug Tunnel, 61

Owner, Brick House Vineyards

Image: Carlin Sundell

Doug Tunnell, 61

Owner, Brick House Vineyards

ON A SUMMER MORNING, in the middle of Brick House Vineyards’ splendor—emerald fields, tranquil pinot noir rows, lazy dogs on the titular brick house’s porch—Doug Tunnell labors to pull a tractor out of a ditch.

It’s an apt moment for a man who pursues an idealistic, experimental career with marked humility. Even though he’s considered one of Oregon’s most forward-thinking vintners, for example, this organic and biodynamic pioneer seems leery of the very idea. “I’m flattered, of course, but I’m just a consolidator,” Tunnell says, noting the ancient history of his craft. “The Jordan Valley exported wine to the Nile in the time of the pharaohs.”

While Oregon’s wine trade has been a haven for freethinkers since it began in the ’60s, Tunnell has driven it toward new frontiers. The Oregon native and oenophile worked as a CBS News foreign correspondent, covering the Lebanese civil war of the early ’80s and European capitals, before heading home to buy a dilapidated hazelnut orchard in 1990 and pursue the then-nascent process of organic winemaking.

“There weren’t many role models,” he recalls. “I think most people were like, ‘Yeah, that TV guy says he’s gonna grow organically. Heard that before.’”

Brick House won quick acclaim—a ’98 pinot noir received 94 points (out of 100) from Wine Spectator, for example. But soon enough even some organic practices (particularly copper-based fungicides) made Tunnell uneasy. He joined a handful of winemakers studying biodynamic farming, a semimystical regime known for lunar schedules and elaborate compost mixtures produced, in some instances, by burying cattle horns full of manure. To Tunnell, biodynamic seemed as logical as holistic.

“It’s a perception of the farm as a living place,” he says. “But on the other hand, great domains in Burgundy farm biodynamically and get $600 a bottle.”

Whatever one may think of the biodynamic method’s more eccentric trappings, Brick House’s results are hard to argue with. One reviewer proclaimed a 2008 pinot “a purist’s delight,” and Brick House’s vintages comfortably fetch top-dollar prices at the on-site tasting table that’s key to the winery’s business model.

Tunnell’s temperament seems ideally balanced for a business that is one part refined aesthetic experience, one part vertically integrated value-added agriculture. “In Oregon, we keep wine down to earth,” he says. “The younger generation doesn’t want all the snooty trappings anyway. If we remind everyone that this product is made by guys with a lot of hydraulic fluid on their jeans, we’ll be good.” —Zach Dundas

I like the “muddy moment” as much as the “aha moment.”

Image: Carlin Sundell

Craig Bramscher, 50

Developer of battery-powered vehicles

IN THE ’70S, Craig Bramscher’s father had a recurring reaction to his young son’s regular fountain-like gushes of ideas. “He has his palms up facing me, then flat to the floor, like, ‘My God, could you please stop,’” Bramscher recalls.

The founder of Brammo Inc, the Ashland-based company Bramscher says is the first in the country to roll out a production line of electric-powered motorcycles with enough guts to be speed-freak fun (and freeway-worthy), began building his ideas at an early age. A clay-pigeon launcher became a trailer-top newspaper launcher for his bicycle-powered delivery business. He fitted small, plywood boats with big engines to go fast. By high school, he had contracted what he calls “machine lust,” buying basket-case motorcycles that had more problems than working parts, just so he could tear them apart and put them back together.

Although trained as an architect, Bramscher found his strong suit was putting business ideas into language engineers could understand. “I had a very strong opinion about the design,” he says, “but that wasn’t probably my forte.” His creative juices run most freely where others’ bog down in what he calls “the muddy moment”—when a problem’s solution is clearly visible but the path to it is not. It’s a feeling Bramscher says he enjoys as much as the “aha!” moment. What some people call dumb ideas, he contends, are just part of his arsenal for the future.

For example, when Bramscher sold his first company—an Internet start-up in the go-go ’90s—on “a really lucky day in the stock market,” he went shopping for a sports car. At the dealership, he found that his tall frame didn’t fold very well into the low-slung seats. The experience sparked an idea to start a company to build sports cars for “American-sized guys”—what became Brammo. The first design, a fully built 12-cylinder supercar prototype, still sits in a garage. Yet his pursuit of ever-lighter construction materials and methods led him onto a wildly different path: a motorcycle—the Empulse—so light it could be powered to 100 mph by lithium-ion battery packs where the engine would otherwise be.

Now 50, Bramscher says his teenage machine lust is giving way to other modes of inspiration: going to bed purposely pondering a problem, then “seeing what comes out in the morning,” he says, noting the dadlike reaction from his employees that often follows. “When I walk in [to Brammo] and I say, ‘You know, I had this dream,’ they’re like, ‘Oh no, here we go again.’” —Kristen Hall-Geisler

I want to demystify the whole process of gathering a story.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Joe Sacco, 50

Cartoonist/journalist

OF THE MANY INSPIRATIONS that led Joe Sacco to fuse comics and journalism into a serious new literary genre—using comic books to do long-form journalism about the world’s toughest war zones—the first was a group of grown men in yellow jumpsuits dancing like robots. As a senior at Beaverton’s Sunset High School struggling with his suburban experience, Sacco witnessed a Saturday Night Live performance by Devo playing “Satisfaction” and “Jocko Homo.” The group’s mordant social satire set to a driving techno-punk beat and their name, founded on the idea that technology was “devolving,” put words and images to Sacco’s discontent.

“It’s good to come across things that don’t just open up a door but kick it down,” he recalls before a pile of Bristol-board drawings in his Southeast Portland studio. “Devo showed me it’s possible to take the piss out of society—it’s possible to be satirical.”

Devo became the gateway drug to a whole range of societal malcontents: journalists George Orwell, Hunter S. Thompson, and Michael Herr and political critics Noam Chomsky and Edward Said. Inspired by their abilities to blast away dominant political narratives and reveal instead the lives of the everyday people tossed aside by the juggernaut of history, Sacco studied journalism but couldn’t find a job in the field. So in 1992, he traveled to Palestine to try to marry the reporting he wanted to do with his love of cartooning. “I wasn’t sure what I was doing, but I had to do it,” he says. “Otherwise I couldn’t live with myself.”

The resulting Palestine weaves together his experiences with Palestinian detainees, Israeli soldiers, and international journalists in stories that are revelatory, heart wrenching, and self-deprecatingly funny. It won the prestigious American Book Award in 1996 and inadvertently established the new genre of comic-book journalism. It’s a bookstore shelf Sacco has continued to fill with reporting on the ’90s Balkan wars and, most recently, with Footnotes in Gaza, a 418-page graphic tome about two 1956 Israeli massacres of Palestinians—massacres that continue to shape the Palestinian psyche even though the rest of the world has long since forgotten them.

“Most cartoonists are navel-gazing moles holed up in apartments,” says Craig Thompson, another Portland-based graphic novelist who has won international accolades. “Joe’s work extends far beyond comics in its sociopolitical relevance.”

Sacco is currently at work on a book with former war correspondent Chris Hedges about Camden, New Jersey, the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, and coal mines of West Virginia. Places, as Sacco wryly puts it, where “capitalism has done its finest—or its worst, depending on your perspective.”

“Basically, if something hits me in the gut, then my brain goes in that direction,” he says. “If I get wrapped up in the emotion, that’s where I’ll direct my energy.” —Aaron Scott

My discovery of cycling is just a metaphor for the whole country.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Mia Birk, 44

Cofounder, Alta Planning & Design

THE STORY OF MIA BIRK, the activist and thinker who helped make Portland the nation’s cutting-edge capital of bike transportation, begins with chomping Dunkin’ Donuts, watching Gilligan’s Island, and rolling along the highways, Texas style.

“By the time I was a teenager, I was overweight,” Birk says. “I rode in the car every day, everywhere, in the car-addicted culture of Dallas. I was Middle America in every way.”

She started riding a bike in college, at first to stand up to her brother’s whimsical challenge to her environmental leanings. Biking soon blossomed into an obsession, and later—after her Johns Hopkins masters degree in international relations and economics and a stint working in energy conservation—it became a job, too. Birk served as the City of Portland’s bike coordinator from 1993 to ’99. In those days, she recalls, Stumptown was almost as bike hostile as any strip of American asphalt.

“People think Portlanders just drank some microbrew one night and started riding bikes in the morning,” she says. “Not the case at all.”

In fact, Birk faced bitter public meetings and a car-centric official culture. But her greatest asset may be her ability to create change inside the inertia-laden system. Early on, she mobilized citizen support to push a bike-network plan through city council. She then nudged that plan into reality, one grisly traffic-engineering problem at time: fighting federal regulators, facing down a dubious Oregonian, and cajoling reluctant city maintenance workers to get actual things, from colored bike lanes to the Eastbank Esplanade, built.

In each case—and Birk’s recent memoir, Joyride, recounts dozens—she applied an idealistic belief in cycling to a specific urban obstacle and the practical politics required to overcome it. “There are political battles behind every single piece of infrastructure that exists,” she says. “To succeed in that arena, you have to build teams.”

By the time the Portland changes truly took hold, Birk herself had moved to a team of her own. Now president of Alta Planning & Design, she leads a 75-strong staff of engineers, planners, and landscape architects who execute similar plans for cities large and small, in the United States and around the world. (The firm even completed a cycling plan for, yes, Dubai.)

“It seems like, again and again, I’ve worked to take something that’s really small and make it into something larger,” Birk says. “I’m trying to teach people to look at their cities’ landscape and imagine what might be possible.” —Zach Dundas

I don’t write for readers. I write for me. And I always have.

Image: Carlin Sundell

Jean Auel, 75

Novelist

CLOSE TO MIDNIGHT one evening in 1977, inspiration struck Jean Auel. Then a 41-year-old mother of five, she imagined a short story about a young woman living 30,000 years ago among a people who were not her own. Her family snugly tucked in their beds, she stayed up into the early morning, writing a rough draft. Soon, she had become a woman obsessed with simple, everyday lives of prehistoric humans.

“When I got into reading and finding all this stuff out, I kept saying, ‘Why don’t I know this? Why doesn’t everybody know it?’” Auel recalls. “‘Well, because it’s not accessible. I’m going to make it accessible.’”

Beginning with the 1980 classic The Clan of the Cave Bear, a story about a Cro-Magnon girl named Ayla living among a Neanderthal clan, Auel’s Earth’s Children series spans six books and 1.7 million words. By the time she released the final book in the series last March, 34 years after that initial spark of an idea, Auel had sold over 45 million copies of Ayla’s story in more than 30 languages.

“Ideas float in the atmosphere. Ideas are not hard to get,” says Auel, who still writes mostly at night. “It’s what you do with them.”

Like Ayla, Auel has made herself right at home as an outsider. Despite no formal training in archaelology (she holds an MBA earned going to night school), she counts among her closest friends some of the world’s most sought-after paleoanthropologists and archaeologists, such as Jean-Philippe Rigaud, Ian Tattersall, and Chris Stringer. She frequently receives invitations to scientific conferences and presentations. The interspecies crossbreeding Auel first imagined in Clan of the Cave Bear—and widely pooh-poohed by all but a few scientists—turned out to be true.

“I know young men,” shrugs Auel. “You start getting people together, and you’re going to start exchanging genes. That’s just the way it is.”

Still, Auel has no illusions that she is anything but a novelist first. At 75, she continues to find fusing science and fiction equally exciting and excruciating. “By the time I get through a night of writing, I’m drained,” she says. “It’s all coming out. Like I had antennas coming out of all 10 fingers and all 10 toes.”

“But I’ve got this insatiable curiosity problem,” she adds. “I hope I never lose it.” —Martin Patail