James Franco’s Private River

River Phoenix’s disheveled pompadour, furrowed brow, and guilty sidelong glances. Keanu Reeves’ puppyish open-mouthed grin as the wind ruffles his feathery mane. Recut by doe-eyed fanboy turned fledgling director James Franco, Gus Van Sant’s My Own Private Idaho footage has never looked better than it does in My Own Private River.

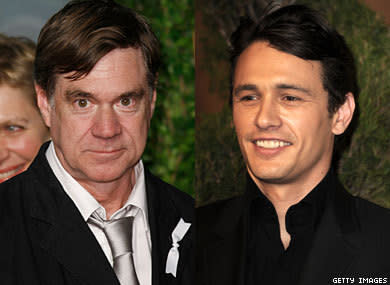

This past Sunday, a nearly sold-out crowd (replete with male and female Marla Sokoloff wannabes) welcomed silver screen Adonis James Franco and renowned Portland-based director Gus van Sant to the Hollywood Theatre. The duo, who forged their friendship on the set of 2008’s Milk, prefaced Franco’s recut with a 30-minute discussion followed by a Q&A session (Read: Franco induced swoon-fest). What were we going to see? Almost all cutting-room-floor footage, pieced back together to create a vignette of the original narrative from its negative space. What else is new? Well:

Less Talk, More Silence, More Stipe

For a novice director, Franco has made some really astute decisions. Seemingly with no fear of offending his hero Van Sant, he’s wisely omitted the pseudo-Elizabethan dialogue that had been a key feature of the original film. Choosing longer takes and more disorienting angles, he lulls the audience into a meditative right-brained reverie. With the addition of a couple custom-crafted Michael Stipe songs, the mood is set for motorcycle rides and leaf-strewn park romps.

Less Romance, More Family

The temptation at the time of its 1991 release was to look at Idaho as a young gay romance—after all, it was one of the first “mainstream” pictures that even implied same-sex love, released in the same year as the sapphic Fried Green Tomatoes, and predating the more overt Brokeback Mountain by 13 years. At the time, the notion of two Hollywood hunks in a cuddle puddle overshadowed all subtler themes. But in his pre-film talk, Franco confessed a different reason that the original film had meant so much to him as a teenager: “I guess I was really fascinated by this idea of forming your own family,” he said. “I come from a great family, but when I was younger, I definitely had this feeling like, ‘where are my people? where are the people who truly understand me?’” Hence, in Franco’s edit, Pheonix is more orphaned urchin, than he is jilted lover. A failed quest to connect with his father or find his mother also ends up robbing him of his brother-in-arms, and in the final scene, we see him sleeping alone on the streets, and trying in vain to hit up his former hustler friends for food and drugs.

Don’t open that door!

Watching River Phoenix snort (what looks like) cocaine is, in 20/20 hindsight, almost exactly like watching a nightgown-clad horror movie heroine investigate a strange noise. You know what’s going to happen next, and you know it’s gonna hurt.

Meanwhile, Keanu Reeves…

Though they’ve set a permanent place at the table for River Phoenix’s ghost, Van Sant and Franco made little mention of costar Keanu, whose (Dog) star seems to have lately faded. One wonders if Reeves was really too busy promoting his new depressive picture-book Ode to Happiness to join this conversation, or if he wasn’t invited because Franco (a new feathery-haired stoner-role actor made good) is essentially “standing in.” Better to burn out than to fade away, eh? (Well, for the purpose of the next part of our analysis, the kid’s back in the picture.)

Back-stories

Born in Beirut to a costume designer and a heroin dealer, Keanu Reeves began his career at age nine during his mother’s short-lived marriage to Hollywood director Paul Aaron, the second of her four husbands. Meanwhile, River Phoenix’s “hippieish” parents spent his childhood following the Children of God cult as far as Venezuela, before doing an about-face to Hollywood and getting all 5 of their children hooked in with a casting agent when River—the eldest—was just 10. So when Reeves and Phoenix “acted” like disoriented kids navigating a landscape of existential confusion and exploitation in Idaho—in all likelihood they were just revealing their personal truth.

But whence James Franco’s edge? Compared to the actors he champions, he comes from a place of privilege. At 20, the son of well-connected Stanford grads dropped out of college against his parents’ wishes to pursue acting. He took a night job at McDonald’s to fund his alternative education—only to be quickly relieved of his debt by his professor the moment he showed promise. While Phoenix’s and Reeves’ entry into acting seems to have brought them in from the cold, Franco’s looks more like an attempt to escape middle-class conformity by experimenting with deprivation and challenge. But even through this concerted effort, it seems that can’t-lose Franco couldn’t shake his safety net.

Ironically, folks on the societal fringes (like the hustlers portrayed in this film, or quite possibly the men who portrayed them) share a key trait with the socioeconomically blessed—in short, an “I can get away with anything” attitude. Beggars have nothing to lose, and choosers have nothing to prove—so both groups tend to have fewer inhibitions than the workaday compromisers in the middle. Why bring this up? Well, when Franco says he used to yearn for “people like him,” our best guess is that he was resisting the professorial types who raised him, as well as his fellow workers in fast food, because in their way both groups represent the middle ground. He seems to identify more deeply with characters like Phoenix and Reeves on both far ends of the socio spectrum, bonding on their mutual lack of inhibition. (Deftly demonstrated in Franco’s nervy request that Van Sant hand over this film footage.)

Fries With That

Franco’s aforementioned fast food experience must have haunted him as he cut the movie’s final scene, in which most of the erstwhile hustlers (besides Phoenix’s down-and-out character) have taken day jobs as fry cooks. The dialogue and pacing are so realistically mundane, they practically give a documentary feel, and Franco’s choice to use them hints at his having “been there.”

Private LA?

In addition to making the new cut out of old footage, Franco decided to exhume one of the screenplay’s rough drafts, and shoot it on Super-8 film. Ghosts is the story of two younger Chicano hustlers in LA, one of whom suffers an inconvenient affliction: narcolepsy. Nodding off at dangerous moments, George relies on his capable friend Ray to rescue him from scrapes. As in Idaho, there’s a motorcycle ride, a bathtub scene, and a creepy German older-man client (played by the original Idaho actor, Udo Kier). Although it’s very nicely shot, this script, especially when compared to Franco’s River, feels repetetive and incomplete—and hence the film presents as more of an exercise in variation and mimicry (and, incidentally, a screen test for one of Leonardo Dicaprio’s godsons) than a viable work in its own rite.

The entire tableau of youthful desperation, puppy love, gritty street b-roll and scenic splendor was a lot to take in—really almost too much—and it took Culturephile a week to chew through. But overall, self-styled film student Franco earns a gold star.

For more about Portland arts events, visit PoMo’s Arts & Entertainment Calendar, stream content with an RSS feed, or sign up for our weekly On The Town Newsletter!