The Arlene Effect

SINCE 1961, Arlene Schnitzer has shown, sold, and bought more Portland-made art than just about anyone. She ran the city’s first truly professional gallery for 25 years and, with her late husband, Harold, endowed the contemporary galleries, a curatorship, and a biennial award at the Portland Art Museum. But on a sunny March morning a couple of months before the first-ever exhibition devoted entirely to her own local art collection, she is fidgeting, folding and unfolding her arms, and making faces.

“I hate being photographed,” she says, her sandy voice rising a gravelly octave as she sits on her living room sofa, wearing a typical ensemble of brightly patterned blouse and dark blazer. “I just hate it.”

What Arlene Schnitzer prefers is show and tell. Show, tell, and touch.

The day before the photo shoot, the 83-year-old darts between paintings, sculptures, and the various other objets d’art in her Southwest Hills home with the speed and certainty of a pinball bouncing bumper to bumper. Every piece inspires a story, of her personal connection with either the artist or the person she bought it from, each episode punctuated with a gleeful affection for the actual thing. And things she has: paintings by Northwest masters like C. S. Price, Kenneth Callahan, Morris Graves, Mark Tobey, Louis Bunce, Michele Russo, and Lucinda Parker, sculptures by Mel Katz, Lee Kelly, Betty Feves, and Debra Butterfield, all of it jumbled together with all manner of other things. Very other. There are the 19th-century Russian trompe l’oeil silver cases. There’s the 18th-century “Japanned” Queen Anne bureau. A chandelier from Murano, Italy. A trio of 18th-century Venetian chairs. Across one fireplace mantle is a lineup of tiny, intricately carved, turn-of-the-20th-century wood toys from Kobe, Japan.

Fountain Gallery cofounders Edna Brigham, Helen Director, and Arlene Schnitzer pose with a painting by Michele Russo.

“I got them at an antique shop on West Burnside that a merchant seaman opened,” she recalls, showing that, with the touch of a finger, the figurines pound drums, spoon food, and stick out their tongues. “I’ve had them for about 61 years now.”

With almost anything three dimensional, Schnitzer offers a quick lesson in how it works or fits together, or, in a favorite pastime with anything smooth, she just rubs it. “Ooooo,” she exclaims, her voice pouring into a high squeal of “I just love you” as she pets the belly of an early ceramic torso by the celebrated Bay Area funk artist Robert Arneson. She bought it out of his studio while he was still in graduate school.

The upcoming exhibition, Provenance: In Honor of Arlene Schnitzer, opens May 12 at the University of Oregon’s Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art (named for her son, an equally energetic collector, primarily of prints). Rather than try to capture the sprawl of her collection, the show will sample only 44 pieces by Northwest and Bay Area artists, according to curator Lawrence Fong, “to focus on Arlene’s relationships with the artists.” For certain, her personal rapport with painters and sculptors has shaped her collection at every step, and shaped Portland in turn. But to understand her relationship to art—to the things—you need to swing open the doors to her house, a kaleidoscope of colors, patterns, textures, and forms akin to a huge party in which every guest is having its own separate conversation with the host.

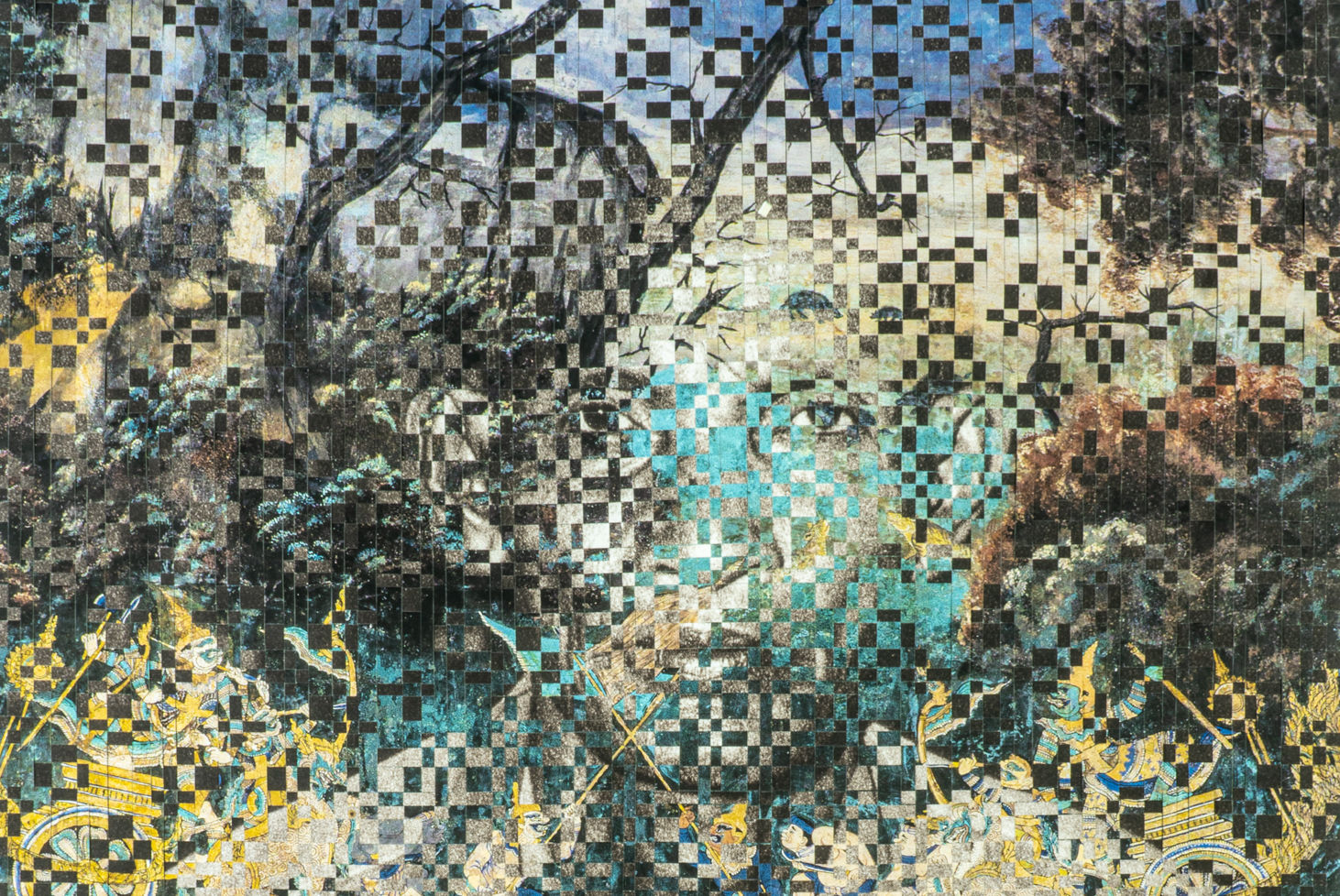

Morris Graves’s 1931 painting Brazilian Screamer, top, is surrounded by a quartet of ’20s- and ’30s-era C. S. Price paintings. Atop a Ming Dynasty table is a Han Dynasty earthenware beast and cart. Below, a collection of pots by Oregon artist Frank Boyden is flanked by Han bronze pots.

Image: Brian Lee

While growing up, as Schnitzer likes to tell it, “‘Art’ to me was somebody’s name. I don’t even know that I necessarily had anything on my walls.” Her father, Simon Director, owned the city’s premier home store, Jennings Furniture, then at SW 10th Avenue and Washington Street. Her mother, Helen, worked with him, overseeing the interior decoration department and styling homes and offices throughout the region. A frequent mother-daughter outing was to Meier & Frank’s 10th-floor tearoom, antique department, and layaway window, where Helen Director was a regular, imbuing Arlene with a lightning eye and quick-draw wallet for objects.

“I make decisions quickly in everything: in fabrics, in furniture, in art, and husbands,” she says. “I proposed on our first date, you know!”

That acquisition, first spotted when a young Harold Schnitzer winked at her in a movie theater in 1949, resulted in nuptials a couple of months later, and a partner in business, philanthropy, family, and art, until his death last year.

Her first encounters with visual art came in classes at the Portland Art Museum School, where she enrolled in 1958 because, as she tells it, “I wanted something to do, and the hours fit.” The often-harsh critiques soured her on making art herself, but she loved the history classes. “I walked into art school, and that was it for me,” she says. “It was like I got home and found myself. I’d never been touched by anything like that.”

In particular, she took to lectures by an erudite, Yale-educated painter, Michele Russo. He had escaped World War I Italy to become a dedicated communist—less political than philosophical—symbolized in his frequent admonition, “I’m a working man,” and the black lunch pail he swung by his side during each day’s walk to the studio. “He was totally unbigoted, unprejudiced,” she recalls of her long informal mentorship with Russo, pointing to the trademark androgynously abstracted figures dancing in a trio of the artist’s postcard-size drawings in her bathroom. “I don’t think he thought in terms of male, female, wealth—certainly not wealth. All he cared about was the mission of art.”

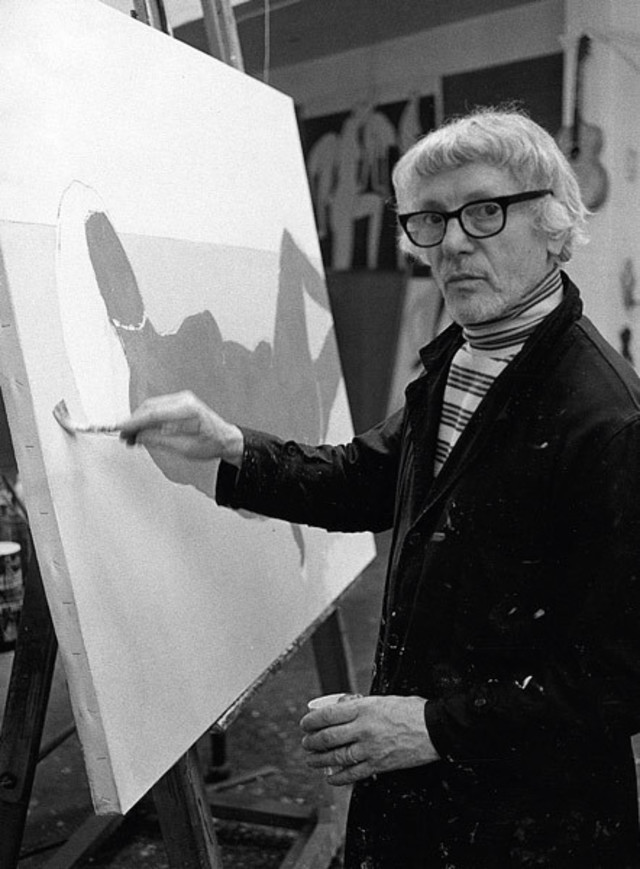

Italian-raised painter Michele Russo inspired Schnitzer with history lectures at the Portland Art Museum School.

At the time of these early encounters, there were few opportunities, beyond cafés, a small gallery at the museum, and Reed College, for local artists to exhibit, let alone sell their work. When a group of the museum school’s faculty wanted to open a co-op gallery in 1960, the then 31-year-old Schnitzer deployed her real estate connections to help. But when the members turned her down (“It’s nothing but junk wealth,” she recalls Russo’s telling of one artist’s rejection—an anti-Semitic-edged reference to Harold Schnitzer’s family’s roots in the scrap-metals business), she decided to open a gallery on her own, initially partnering with her mom and a friend, Edna Brigham. Russo pledged to help her install the shows.

In search of artists, Schnitzer turned to a well-connected couple who held themselves somewhat aloof from the local art scene: Carl Morris, a painter, who cavorted with the New York School circle around Robert Motherwell, Mark Rothko, and Barnett Newman, and his wife, Hilda Morris, an equally accomplished sculptor. They, in turn, introduced Schnitzer to a young PSU professor, Robert Colescott, and to their close friend in Seattle, the Northwest master Kenneth Callahan. And so connections multiplied up and down the coast. On November 28, 1961, the trio of women opened their space at 66 SW Second Ave on Ankeny Plaza. They named it the Fountain Gallery after the water feature just outside its door, the one with the C. E. S. Wood quote, “Good citizens are the riches of a city.”

Louis Bunce’s Beach, Low Tide anchors a wall Schnitzer says never changes. Mark Tobey’s undated Market Figures hangs to the left, and Michele Russo’s mid-’50s White Daisies is at right.

Image: Brian Lee

For the next quarter century, the Fountain Gallery was the center of Portland’s art scene. “Arlene had the social contacts to really raise the sense of collecting,” says George Johanson, one of the few artists of the era still around. “She had a real commitment to the importance of local art and became an evangelist about it to a huge group of people who had the money to buy it, but had never looked at it before.”

Schnitzer chuckles about how, against the common gallery practice (and Harold’s advice), she stayed open Friday nights, a move that netted her first sale: Robert Arneson’s She-Horse with Daughter. Soon she was parlaying her connections to individuals and building collections for local banks, law firms, corporations, and even national giants like US Steel. She also filled the offices of her and Harold’s own expanding real estate company, Harsch Investment Properties, with art. And for their landmark Claremont Hotel in Oakland, they commissioned outdoor sculptures and works for the hallways and rooms. Many a month, she concedes, Harold’s purchases were what kept the Fountain in the black.

Late-19th-century Russian tromp l’oeil silver is among Schnitzer’s many collecting passions.

Image: Brian Lee

“Harold loved the artists; he loved the art; he loved walking into the gallery; he loved that it was doing something in the community,” she says. “And the harder the work was to sell, the more supportive of the artists he was.”

In 1986, Schnitzer closed the Fountain Gallery with a 25th anniversary exhibition. “I had such a monopoly,” she says. “I thought, if I closed, the intimidation factor of others starting galleries would go away.” It did, and a new generation of younger, smaller galleries sprouted.

While she has continued to buy local art, Schnitzer shifted the acquisitiveness she describes as “an addiction,” along with her formidable purse, to Han Dynasty Chinese art. On first encountering the iridescent bronze of a 2,300-year-old wine vessel known as a hu, “I was instantly struck and fascinated,” she says. “There’s such a purity of form. I mean look at this,” she adds, rubbing her thumb over a jade belt hook, then a white jade carving, all of which would lie behind thick glass in any museum. “We’re talking over two thousand years old.”

Working with noted Asian art dealer J. J. Lally, she and Harold built one of the most significant collections of Han Dynasty Chinese art outside of China. The Portland Art Museum dedicated an exhibit to it in 2005: Mysterious Spirits, Strange Beasts, Earthly Delights: Early Chinese Art from the Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Collection.

Schnitzer explains her transoceanic leap of passion as an effort to avoid collecting any “high art that competed with my heart, which was regional artists.”

The homes of collectors of Schnitzer’s means and influence often stand as analogs for how they shape their cities’ larger artistic scenes. Virginia and the late Bagley Wright’s Arthur Erickson–designed Seattle compound overlooking the Puget Sound, for instance, is filled with everything from heroic ’50s-era abstractions to turn-of-the-latest-century video art—the same kinds of things with which she’s stocked the similarly spare and monumental Seattle Art Museum. Closer to home, timber heiress Sarah Miller Meigs occasionally opens her airy Pearl District pied-à-terre loft, dubbed the Lumber Room, with selections of her growing collection of international and regional art and sharply focused exhibitions by invited curators. Nike CEO Mark Parker built a barn-size personal temple designed by the architect of the Nike World Headquarters for his collection of sci-fi toys.

Schnitzer in 1963 in the storage room of the Fountain Gallery

For Schnitzer, art is decidedly personal and unexalted. She lives in the same house the couple bought in 1974, a vernacular, Northwest modern rambler that is great for art but was built, she freely notes, rather cheaply and poorly. In the foyer, an unusually vibrant-hued 1931 Morris Graves landscape hangs above an elemental, clay Han-era beast and cart sitting atop a Ming table that straddles a cluster of ceramic vases by the coastal artist Frank Boyden. In the master bedroom, a gleaming white porcelain Jeff Koons West Highland terrier vase is filled with flowers handmade from antique fabrics.

“Most people who show these, the puppies, they have these big red fake paper flowers,” she says as she rearranges the stems in the Koons that she bought for $450. “I bought these in an antique shop 15 years ago.”

In a nearby hallway hangs the first purchase Schnitzer made from the Fountain Gallery for herself: a black-and-white print made with a hand-cut plate by Dennis Beall. Steps away in the dining room is one of the most widely exhibited and published paintings she owns, the late Robert Colescott’s Sunday Afternoon with Joaquin Murietta. Only the deepest student of West Coast art would know Beall. Colescott, by contrast, is in every American art history book, having risen from PSU professor to the 1997 American representative to the Venice Biennale. He was the pioneer of black satire in 20th-century art. Yet, Schnitzer’s enthusiasm for both works is equally effusive and consumed with the details: the deep black tones and textures of Beall’s tiny abstract print and the agile brushwork shaping the basket of food in Colescott’s riotous caricature of a nude black woman lounging with the Mexican/Californian folk hero Murietta, a send-up of Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass.

To the question “What has guided you most as a collector?” Schnitzer answers without pause: “My heart.”

“God, when I think about it,” she recalls, “I could have had a Warhol Campbell’s soup can for $50—the flowers and Maos for $1,200. But I couldn’t do it. It was like I would degrade my mission to support the local artist, to keep them here and working. It sounds Pollyanna, but I really mean it.”

Editor's Note: The Portland Art Museum's exhibition In Passionate Pursuit: The Arlene and Harold Schnitzer Collection and Legacy will feature more than 100 works drawn from the collection of Arlene and Harold Schnitzer, including paintings and sculptures by Northwest and West Coast post-war masters, Han dynasty Chinese art, Native American ceramics, and more. The exhibition, which will also explore the couple's incredible impact on the region's arts and artists, opens October 18, 2014, and runs through January 11, 2015.