Review: Portland Center Stage’s Anna Karenina

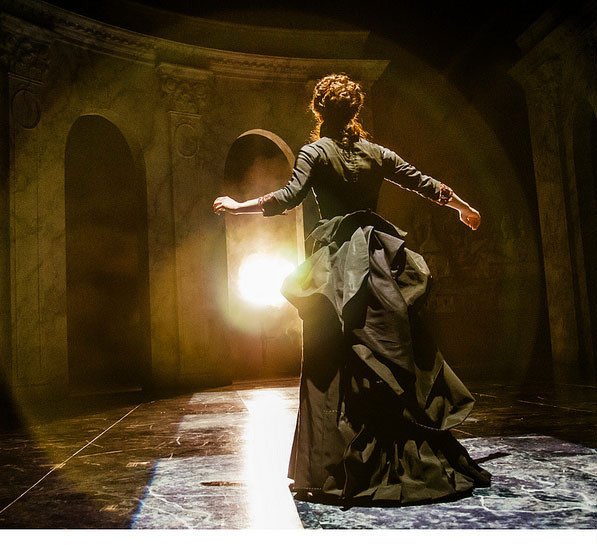

Kelley Curran in Kevin McKeon’s adaptation of Anna Karenina, playing through May 6 at Portland Center Stage. Photo by Patrick Weishampel

Just as every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way, to quote the opening sentence of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, every theatrical adaptation is unhappy in its own way, too. Not to say that there aren’t many wonderful adaptations, but just that the adaptation process is a struggle that, much like a family, involves fights, oversights, and sacrifices, from which few exit unscathed.

Which is why the success of Seattle writer Kevin McKeon’s adaptation of the classic at Portland Center Stage, directed by Chris Coleman and running through May 6, is no small feat. McKeon manages to condense Tolstoy’s sprawling masterpiece about a woman whose love rattles the prison of her social situation into a brisk, ensemble-based production that captures the tragedy of the original, adds a slightly anachronistic humor, and—the gargantuan length of the original be damned—does it all with intermission in under three hours. Whew!

As quick summary, Anna Karenina, considered one of the greatest novels of all time, tells the story of a married, aristocratic Russian woman who falls in love with another man, eventually abandons her husband for him, struggles with her consequent exile from high society and inability to visit her son, and ends tragically. Meanwhile, two contrasting couples serve almost as alternate endings: Anna’s brother’s wife accepts his philandering and they move past it in a mutually agreed upon ignorance of sorts, and that wife’s sister marries a painfully honest but existentially awkward man for love and the two come to respect each other.

In order to cover all the explication of the novel, McKeon uses a clever fix of ensemble narration: one character says one line and another says the next, often taken straight from the novel. Combined with Coleman’s incredibly tight blocking—they’re 89 costume changes between the 17 actors in Act One alone!—the story unfolds like clockwork.

Fascinatingly, McKeon’s method recalls another powerful ensemble performance currently running, Portland Playhouse’s Brother/Sister Plays. While Brother/Sister’s ensemble narration creates a sense of the mythological from the everyday (read our review here), Anna Karenina’s creates an overpowering sense of inevitability—Anna cannot escape the fate of her social position no matter what she does. And it has the same unfortunate side effect of somewhat distancing the play from its emotional impact. It’s not until the end, when Anna is on stage alone with no further narration, that the emotion of the story becomes truly palpable, building to crescendo with the force of a, well, steam engine.

The grand marble pillars of the set, the intricate costumes, and the evocative lighting (designed by G.W. Mercier, Miranda Hoffman, and Ann Wrightson, respectively) are utterly gorgeous. At points, the theater appears all the world like a Maxfield Parrish painting, if he’d romanticized his fellow Victorians instead of Grecian maidens. But though the costumes are period, McKeon doesn’t make the same overture with the language, which is surprisingly modern and adds a layer of humor to the tragedy that keeps the play fresh—although I think Downton Abbey has shown that you can include zingers while staying period appropriate, as opposed to taking McKeown’s at times almost Clueless route (e.g. “Fuck the privilege”).

The humor is amplified by Keith Jochim, who practically steals the show as Anna’s husband Karenin, playing him with the emotionless dryness of a bureaucrat who doubts nothing and schedules everything—even sex. Kelley Curran, who had to learn the role in less than a week after the original actress took ill, plays Anna with an inner steel that devolves to paranoid hysteria by the end. Michael Sharon plays her lover, Count Vronsky, with turns equally seductive and slimy, devoted and selfish. And R. Ward Duffy stands out from the ensemble with affable charisma as Anna’s cheating brother, Stiva.

All in all, under Coleman’s able direction, it’s an epic, entertaining journey through a classic. We can just be thankful that McKeon wasn’t paid the same way as Tolstoy: by the word.

For more about Portland arts, visit PoMo’s Arts & Entertainment Calendar, stream content with an RSS feed, or sign up for our weekly On The Town Newsletter!