A Tour of PAM's Ellsworth Kelly/Prints Exhibit with Kelly's Partner

Editor's Note: We're reposting this tour from June because Jordan Schnitzer will be speaking with the art museum's director, Brian Ferriso, about collecting Kelly's work this Thursday, Sept. 6 at 6pm at the museum. The exhibition closes on Sept. 16—don't miss it.

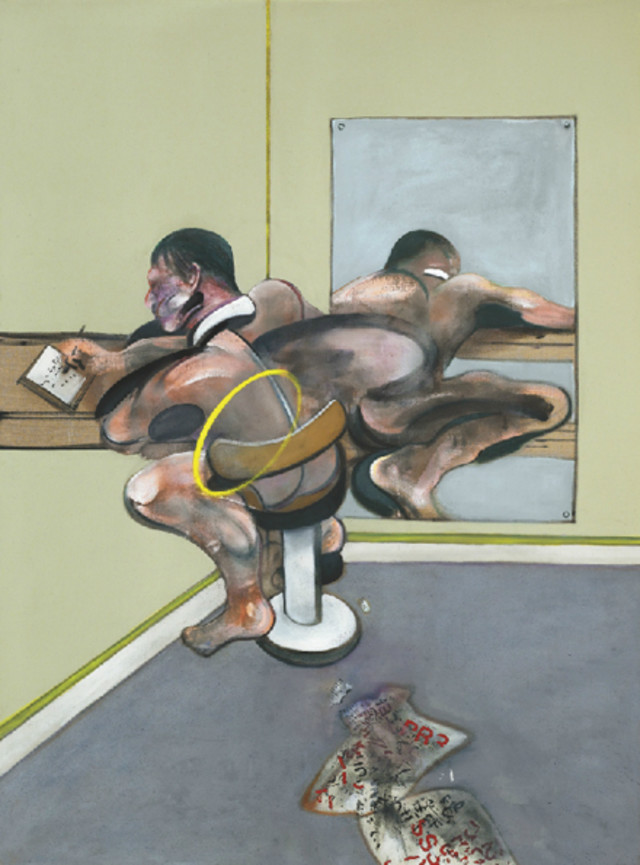

We’re staring intently at Francis Bacon’s masterwork "Figure Writing Reflected in Mirror" (1976), which was recently auctioned for $44.88 million after being in a private collection for over 30 years (curator Bruce Guenther made a couple calls to Sotheby’s and was able to get it on loan from the owner before any other museum). It’s believed to be a composite of Bacon and his working class lover and muse, George Dyer, who committed suicide on the eve of Bacons’ retrospective at the Grand Palais, Paris in 1971. He’s sitting on a stool writing a note, his mostly naked body reflected in a mirror, discarded pages strewn on the floor. Eight thousand people lined up to see it when it was first exhibited.

Jack Shear, Ellsworth Kelly’s partner since 1970 and the director of his foundation, puts on his glasses and leans in until he’s about to smudge the paint with his nose. “They never mention this, but it’s those rub on letters,” he says, pointing to the perfect black block letters on the figure’s pages. They have a familiar gloss. Seems the great Bacon got his lettering at the hardware store, though the placard says the medium is oil.

Exhibition Curator Mary Weaver Chapin, Jack Shear, and Jordan Schnitzer

Then Shear wanders over the south stairwell that joins the second floor to the south side of the museum’s entrance hall. Sunlight is streaming through the glass blocks in the wall. He holds his iPhone above his head, takes a close up photo of the corner where the ceiling meets two walls, and brings it back to share. Though each surface is painted the same shade of white, in the diffused lighting, each has a markedly different hue—one white, one grey, one blue. The image is exceptionally rich.

“Would you ever believe that’s not three different colors?” he asks. “If you turn off the mind and look only with the eyes, everything becomes abstract.“ Which gets at the heart of everything he’s been saying this afternoon about Kelly’s work. Instead of depicting the whole story of his subjects, Kelly isolates one facet, one feature, one plane—distilling a singular shape or two from the complex whole.

“Art is about looking at the world differently,” says Shear.

Shear is in town for the opening of the Ellsworth Kelly/Prints exhibition, which draws from the collection of local collector Jordan Schnitzer and comes to Portland from the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, where it was the first major retrospective of the influential abstract artist’s prints since 1988. It’s getting a jump on Kelly’s 90th birthday next year. Kelly himself, no longer up for the travel, is at home painting.

Shear, along with the exhibition curator Mary Weaver Chapin, kindly agreed to give a small tour organized by Schnitzer. Shear is a tall man with a round face and a full head of grey hair. Although dressed in a conservative navy jacket over a khaki shirt, the 58 year old moves with an abundance of energy, gesturing with outstretched bent arms, more reminiscent of a hip-hop emcee spitting rhymes than a photographer who lives in upstate New York with one of the most important artists still gracing the Earth.

After a short introduction, we go to the center of the room to the Suite of Twenty-Seven Color Lithographs (1964-66), a colorful series of the same two rounded shapes in different colors hanging in a line. They give an early vocabulary of the rich colors and shapes Kelly investigates again and again. They also flirt with the viewer’s perception: the shapes in each looking different in size, although Chapin says they actually measured and they’re all the same. On one end sits a print of a lonely green blob.

“Ellsworth’s prints follow what he’s doing in painting at that time,” says Shear. “You have a series plus a singular print. It’s about that subtlety of what he’s playing with the vision and what he’s putting on the paper.”

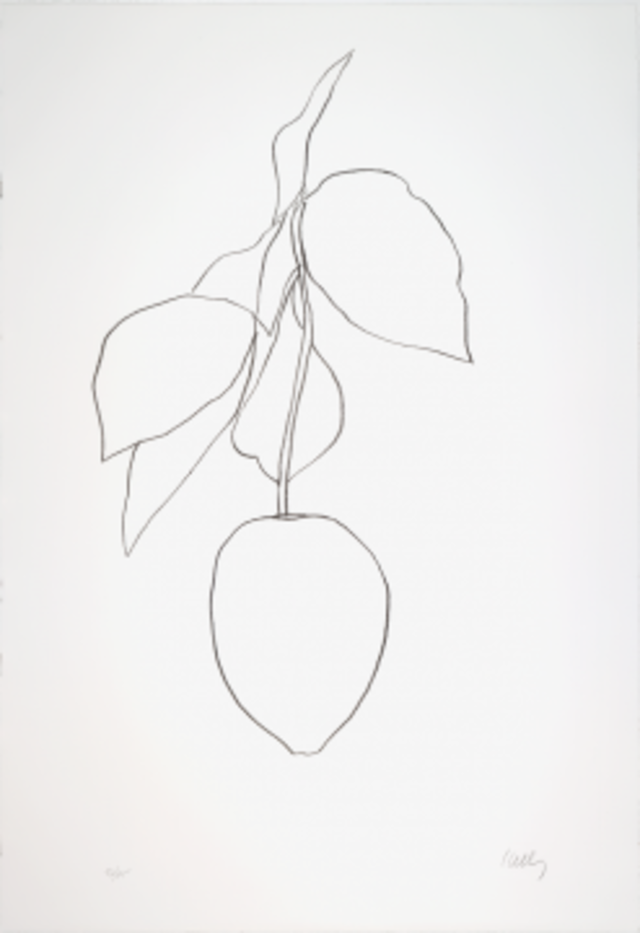

Then we head to the back of the room to take in a series of Kelly’s plant lithographs, each a simple outline drawn without hesitation. “He calls them portraits,” says Shear. “They’re individual plants that he’s looking at, and he is doing a portrait of that particular thing in front of him. Unlike Matisse, who leaves most of his forms open, and they’re more of the essence of the plant.”

When he’s done, Kelly rates his plant drawings. In 1983, Shear rescued one from the D pile, saying it was an A drawing. Now it’s in Kelly’s show of plant drawings at the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

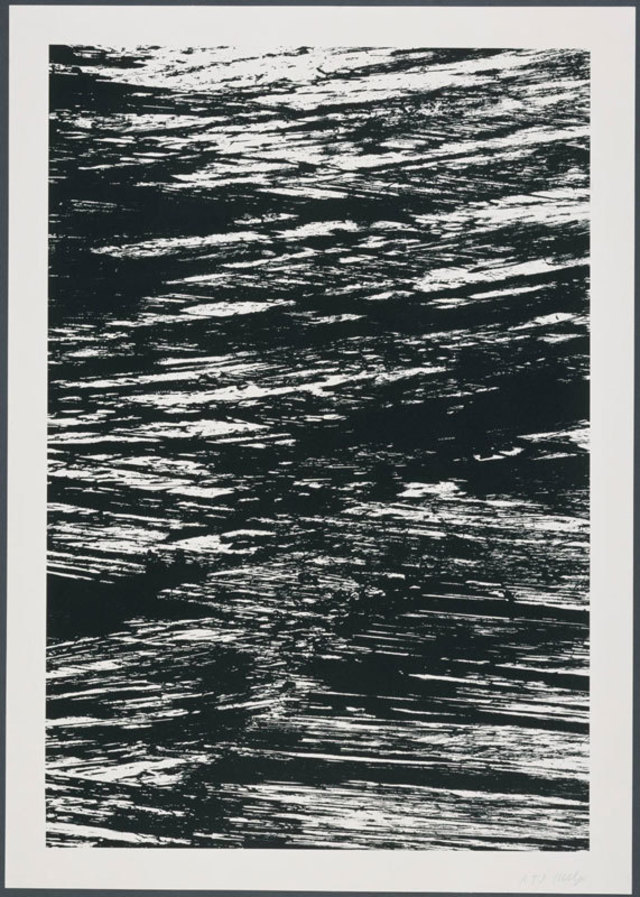

Next we turn around to the States of the River (2005) series. Each is a rough hash of diagonal lines dancing over each other. Though prints, they have an incredible painting-like quality. “Ellsworth was in Basel in a hotel above the Rhine, and they had record floods,” says Shear. “He couldn’t sleep, and there was this rushing water. And you can look out and see all the lights flickering across the water. And the image stuck with him. He couldn’t believe it because it was so powerful. So when you look at this, you basically see this flowing kind of movement, this quality, that Ellsworth created.”

And so we circle around the room. Kelly’s prints are deceptively simple, yet you can get lost in each, sailing around the bold edges of the shapes, sinking deeply into the vibrancy of the colors. Each work is captivating enough to hold an entire wall, but hung in tight succession they create a trajectory for the eye and an incredible sense of movement, particularly in the corridor of black and white prints, where similar shapes tilt in a progression, like they are tumbling down the course of the wall.

“The Warhol, Lichtenstein shows, they’re dead, but when you do a living artist, you get a little nervous,” says Jordan Schnitzer, who’s been hanging back, letting Shear tell his stories. “But Jack got on the phone and said, ‘Ellsworth, you’d love it.’ For his work, some of these rooms are better than LA. You can see these [prints], and see through to other rooms, and see how the works interact with each other.”

Shear tells his favorite story about Kelly. He was extremely sick in Paris in 1954, staying in a fifth floor walkup. He decided that he had to go home, but he was broke. He wired his parents and asked for $200 for the passage, and then $200 dollars to ship the work he’d painted over the last six years in Paris. His parents said they’d wire him $200 and to leave the paintings behind. Instead, Kelly went to all the shipyards, sick as could be, asking for credit. He finally found the Cunard shipping line would ship them under the condition that he paid back five dollars a week until he paid off the full $200. Some 70 of those paintings now hang in major museums, and the only thing that kept them from the rubbish bin was $200, says Shear. “That’s a story about what a true artist is.”

For more about Portland arts, visit PoMo’s Arts & Entertainment Calendar, stream content with an RSS feed, sign up for our weekly On The Town Newsletter, or follow us on Twitter @PoMoArt!