Artist Carrie Mae Weems Comes Home for a Retrospective

Carrie Mae Weems still recalls the day when, as a student at Boise Elementary in North Portland in the early 1960s, her grandfather picked her up from school. Her two best friends came clicking up to her afterward and asked, “What were you doing with that white man?”

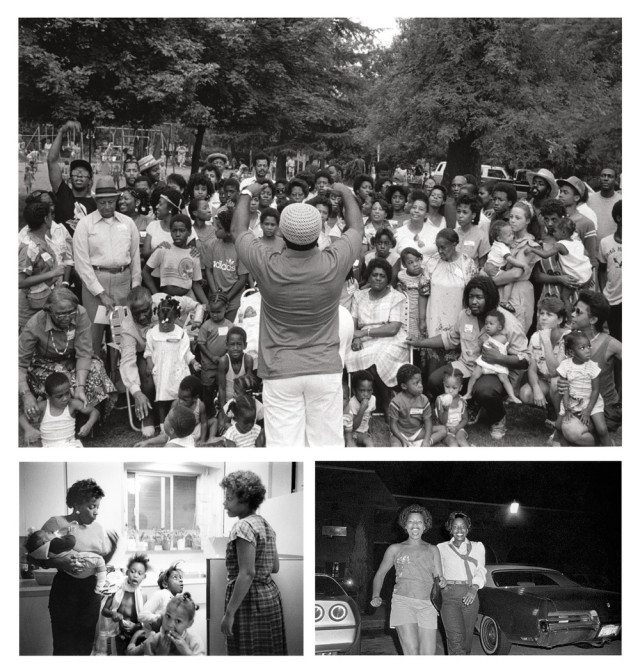

Taken between 1978 and 1984, Family Pictures and Stories documents Weems’s close-knit extended family in North and Northeast Portland.

At first, she didn’t know whom they were talking about. She had never thought of her grandfather, the light-skinned son of a Jewish sharecropper from the Mississippi Delta, as anything but kin.

“It forced me to look at my grandfather differently,” says Weems. “I went home and said, ‘Papa, what are you?’”

Weems’s many variations on that question—directed at her family, her race, her gender, and herself with an incredible courage, love, and humor—led her to become one of the pioneering artists of her generation. Now 59, for the first time she is the subject of a major museum retrospective: Carrie Mae Weems: Three Decades of Photography and Video opens at the Portland Art Museum on February 2. Curated by Kathryn Delmez of Nashville’s Frist Center for the Visual Arts, where it premiered last fall, the exhibit was sparked by a 2008 comment from New York Times critic Holland Cotter: “I don’t know why Carrie Mae Weems hasn’t had a midcareer museum retrospective. No American photographer of the last quarter century ... has turned out a more probing, varied, and moving body of work.”

“Something needs to happen, the dam needs to break, so that super-bad women can step into the world and be taken seriously, very seriously, and not just patted on the head or on the butt.”—Carrie Mae Weems

With a deep belief in equality, not to mention a penchant for spinning tales, instilled in her from an early age by her father, Weems moved to San Francisco at 17 and was given her first camera as a 21st birthday gift from a boyfriend, along with a copy of The Black Photographers Annual, one of the first collections of work by black photographers, such as Roy DeCarava and James Van Der Zee, documenting African American life. “These men and women were changing the way we see and encounter humanity that happens to be dark,” Weems says from her studio in Syracuse, New York, where she has lived since 1996, her warm, melodic voice and candor, like her work, lending an immediate intimacy. “I knew that I wanted to be involved with work that had to do with a shift in perception, not only of black people, but of women and aspects of humanity that have been essentially denied in the canon generally.”

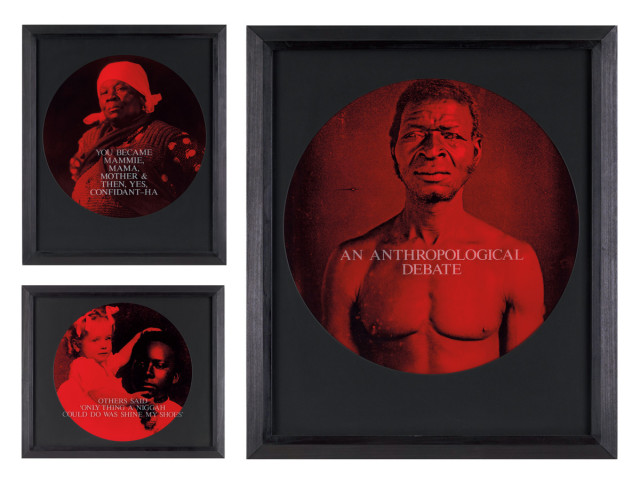

Commissioned by the Getty, From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–96) uses appropriated early photographs and text to reveal how images have been used to stereotype African Americans.

Unlike the many documentarians who travel the world seeking the foreign, Weems initially chose to examine the thing she knew best: her family. Outraged by the infamous 1965 Moynihan Report that blamed the deterioration of “negro society” on “weak families” and female-headed households, she returned to Portland as a UC-San Diego MFA student in 1978 to create Family Pictures and Stories (1978–84), which opens the retrospective. It combines photos with captions and recordings from her relatives to frankly portray a robust and complicated family. Her father holds squirming grandkids in his lap; her mother’s smile lights up a shabby, cavernous garment factory; at least a hundred family members pack together for a portrait in a North Portland park. (“We are the black population [of Portland],” she jokes over the phone. “We are it.”)

In the late 1980s, as an instructor at Hampshire College in Massachusetts, Weems watched her female students struggle with facing the camera in self-portraits, while she herself wrestled with the absence of African American women in contemporary feminist discourse. So she placed herself in front of the camera. Using her sparsely furnished kitchen, she composed a series of photos and wryly written text panels, creating a narrative of a self-possessed young woman’s rites of passage. “She needed a man who didn’t mind her bodacious manner, varied talents, hard laughter, multiple opinions, and her hopes were getting slender,” it starts, before moving through love, motherhood, loss of love, friendship, and independence. With its brazen take on race and unabashed celebration of complex femininity, The Kitchen Table Series won Weems critical attention and showed around the country. “This series generates the power of good theater,” wrote a critic in the Philadelphia Inquirer. “It’s real enough to be believable but it speaks with the intensity of art.”

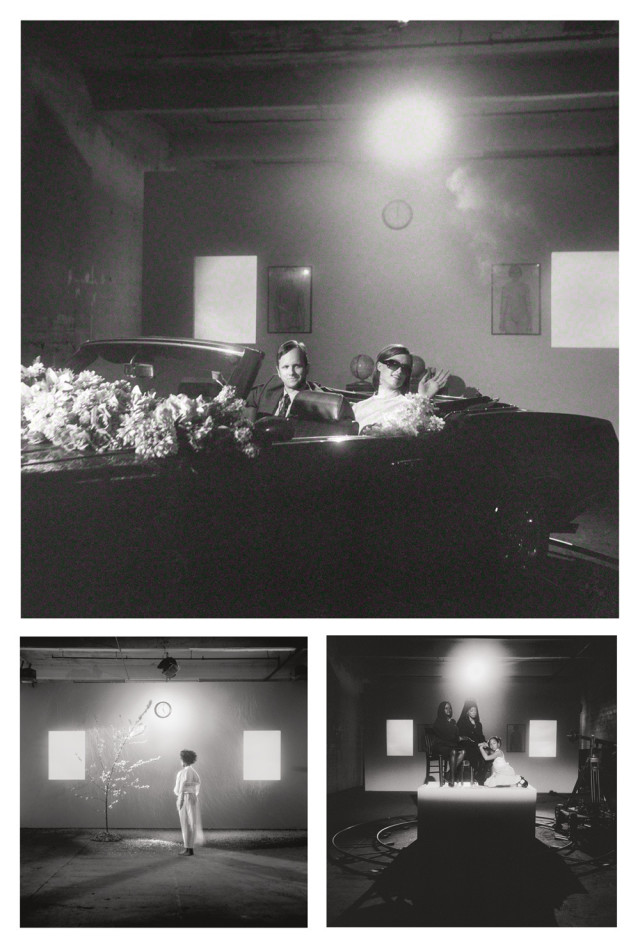

In Constructing History (2008), a series of videos and photographs, Weems worked with college students to re-create pivotal moments from the civil rights era.

In the ensuing decades, Weems has often used herself as subject, although recently she has turned her back to the camera, transitioning to a muse, a guide, and a stand-in for the viewer. “The first thing that happens when you [face the camera], particularly as a black woman, is that people think about you as a black woman and that becomes the dialogue,” she explains. “How do you short-circuit that so you can get to other ideas and notions about the creative world and about life itself?” In the ongoing Museum Series, she photographs herself in a long black dress facing strongholds of high art such as the Louvre, emphasizing her place as an outsider peering in on establishments barred to many. In Roaming, made while on a fellowship in Rome in 2006, she faces historic structures of power, like a ghost through history, a cipher for the grandiosity of civilization and the fleetingness of individual lives.

In From Here I Saw What Happened and I Cried (1995–96), arguably her most unflinching look at race (a series so poignant that the Portland Art Museum’s photography curator, Julia Dolan, says she’s seen viewers elsewhere burst into tears), Weems gathered historic daguerreotypes of African Americans, many of them slaves, tinted the images a deep blood red, and superimposed text telling their history at the hands of white society. The first four read: “You became a scientific profile” “a Negroid type” “an anthropological debate” “& a photographic subject.” By using the second-person pronoun, she implicates each viewer as she turns our troubled past on its head. For Constructing History (2008), Weems re-created significant civil rights movement–era images—John and Jackie Kennedy in their Lincoln Continental, Coretta Scott King mourning her husband’s death, fallen students at Kent State—using college students, who in many cases were unfamiliar with the history. “What happened during that brutal period is what made this moment possible,” Weems says now. “Obama could only arrive out of these ashes.”

While Weems’s work has taken her through the annals of slavery and from Cuba to North Africa to State Department dinners with Hillary Clinton, she continually comes back to something apparent from her earliest work with her family. “In tackling, for instance, the questions of race and gender, ultimately what you’re getting at is the question of love,” she says. “In order to embrace difference, there must be some great level of compassion, on the part of the viewer and the artist, and a profound belief in this pursuit of the most mysterious of all—and that is love.”

Carrie Mae Weems

Three Decades Of Photography And Video

Feb 2–May 19

Portland Art Museum

1219 SW Park Ave

pam.org

(Weems speaks on February 3)