Exclusive Q&A: Behind the Calligram Foundation

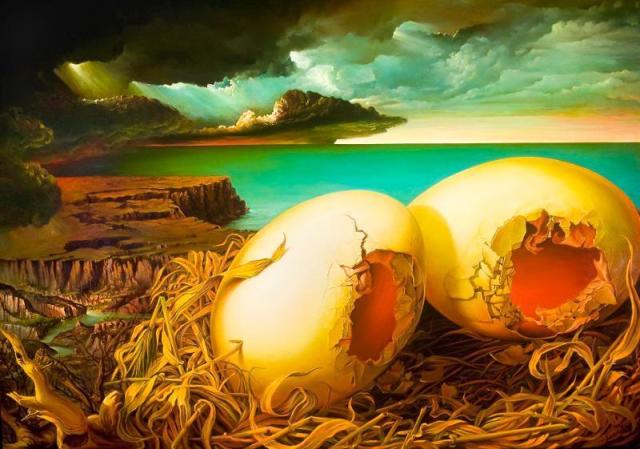

Formerly a portraitist for Saddam Hussein, Iraqi artist Samir Khurshid is free for the first time to paint what he wants, discovering a style marked by intoxicating colors and Dali-esque surrealism.

Last January, the unknown Calligram Foundation and the better-known Falcon Art Community, a series of studios in the giant basement of a NoPo building owned by real estate developer Brian Wannamaker, announced the state's largest visual arts fellowship program to the tune of $150,000, including $110,000 in direct cash stipends from Calligram and studio space from Falcon. The money was spread between five oil painters—Stephanie Buer, Samir Khurshid, Molly Maine, Nathaniel Praska, and Alexander Rokoff—with the express purpose “to support Portland artists’ living expenses, in order to free them to focus exclusively on their art.”

On Saturday, those five artists will show the fruits of their year at a one-night-only group exhibition at 1300 NW Northrup Street from 7–11 pm. For more about the fellows, go to Calligram's website.

Sounds like a dream come true: like in the patronage days of the Renaissance, someone else pays your bills, allowing you to quit your part-time jobs, ignore the grant applications, and do nothing but hone your craft. For an entire year.

But the $110,000 question remains: what or who exactly is the Calligram Foundation?

In their first Portland interview, Calligram’s president, artist Allie Furlotti, and executive director, Satya D. Byock (who’s also a private-practice therapist), sat down with Culturephile in the place it all started, Red E Café on Killingsworth, to talk about the foundation, a new take on an old funding model, and what they hope to accomplish.

Allie Furlotti in "Cold Feet" from "The Funeral" (2009).

Culturephile: First off, what does Calligram mean?

Allie Furlotti: A calligram is a phrase where the typeface represents the word. So “box” written over and over in the shape of a box.

So Calligram arrives in town: a mysterious foundation with a simple website and $110,000 to dole out in its first year. Perhaps then we should start with an introduction. Tell us about your background and why you started Calligram?

Furlotti: I moved up here from Los Angeles about a year and a half ago, and I really wanted to engage the arts community in Portland, because there’s just not enough money, not enough community between benefactors and artists and other artists. I felt that if I could put some money into artists' pockets directly, they could form some community and that would give them a springboard into a world where there was benefactors and patrons, and people would be interested in them, as opposed to, y’know, seeing their art in coffee shops and not taking it very seriously.

Satya Byock: I got involved in working on this project with Allie because I worked with her family foundation a couple years ago. Calligram is a doing-business-as organization related to a much bigger foundation, and because Allie's in Portland, it's a matter of creating space for the artistic community in Portland.

Stephanie Buer's photo-realist paintings capture the gaping yet somehow comforting stillness of derelict, graffitied, urban landscapes.

What is that foundation?

Byock: The Furlotti Family Foundation. No one knows it. It has no website, no logo, no presence. It’s barely an entity. It's a philanthropic organization that gives out about $1.5 million a year to a very broad spectrum of things, and the board is a composition of family members entirely. [Ed. Note: The Foundation gave $25,000 to Portland's My Voice Music youth program and $10,000 to the Circus Project, which also won one of PoMo's Light a Fire nonprofit awards.]

Can I ask where the family's money comes from?

[Ed. Note: While Furlotti originally chose not to answer, she later said that a great-grandfather founded UPS.]

You went to Reed, so you're actually returning to Portland?

Furlotti: I did sophomore to senior year at Reed, 2003-2005, where I got a bachelor's in fine arts.

What sort of art you do?

Furlotti: I do performance art. I started doing sculpture when I was really little—building characters. And then when I went to London [to get an MFA], I turned them into real characters on film. The different characters had whole worlds that they lived in: I would have different friends for each character that I went and saw, different voices, everything. Then I did my master's on impressionist comedy in London, and then I moved back to LA, and the artistic climate was much different. So I decided to move to Portland.

Why Portland?

Furlotti: When I went to Reed, I really loved this city a lot. It’s very egalitarian. I appreciate how nourishing and healthy it is.

Alexander Rokoff is perhaps the best known of the painters, his large-scale portraits of models like Storm Large and Modest Mouse's Isaac Brock in almost mythological settings filling Falcon's halls and hanging in venues such as the mayor's office.

Why did you decide to set up Calligram like the old-school Medici family Renaissance–style model, with a few big patronage grants to a few artists?

Furlotti: Every time I would apply for a grant, the process is awful. I don’t think it does anything positively culturally. You know, telling 10,000 people they didn’t get something after working six months on the application. It just makes me sad. I thought, if you get money directly to the artists and let them do whatever they want with it, that’s real freedom.

Byock: It allows the money to be distributed based on relationships and not bureaucracy. All the artists in this group were nominated. It started through a synchronistic conversation with the Falcon that actually started here [signaling Red E]—two loose entities coming together via synchronicity, realizing that if you can cut out the bureaucracy, the nonsense, the paper forms, the lack of relationship, if you cut out the coldness, there’s much richer opportunity available.

So you picked this last round of artists through a nomination process?

Furlotti: We have a board of people around town who are involved in the art scene. We had each person suggest a few people, we had a look, and went after them that way. Samir is a Falcon artist; Nate and Alexander were previously Falcon artists. Satya found Molly at Coffee House NW.

Byock: Not all were Falcon artists. The criteria was: we wanted all to be craft-oriented—oil painters with a particular level of training. The pool in Portland was not enormous to begin with. But because we were starting quickly, we narrowed our sights.

Perhaps with the exception of Alexander, who had paintings in Mayor Adams's office, none of them are particularly well known. Was the idea to go after emerging and young artists?

Furlotti: Yes. I've had the means to pursue my own dreams in art, and if I didn't have the means to do so, I'd hope that something like Calligram would exist for me. Fueling people's creative impulses—that innate human drive of expression—enriches us all. It's fun for me to be a part of it, to be a part of people's creative lives, and hopefully the support boosts confidence and helps to launch careers where talented people might have otherwise struggled.

With the security the fellowship awarded, Nathaniel Praska transitioned from plein air landscapes to abstract color fields.

Tell me about the show and the work.

Byock: A lot of what happened with the fellowship is all of the artists are painting large-scale works, which is not necessarily easy to sell, but it’s been awesome to see them expand in that way with the freedom, and the work’s extraordinary. Stephanie’s work is smaller scale, and she sold out one solo show in LA and has another coming up. She’s an emerging artist and she’s killing it. So we backed good horses in that respect.

How have the others changed under the auspices of the fellowship?

Furlotti: Nate went from painting plein airs, school of landscape, to moving into contemporary color field painting kind of like Rothko. He has a real poetry behind what he sees. Molly has always painted real Renaissance-style paintings with archetypes, depicting rituals, and she has carried forward really consistently on her path.

Byock: Samir’s a fascinating transition. All men in Iraq had three years of required military service, and his job was to paint portraits of Saddam Hussein, so he’s only done commissions. His skill is extraordinary, he can create a Picasso or Matisse replica in two days, but he’s never had an opportunity to find his own voice. Now he’s finding a voice that blends a very traumatic past with his extreme hope for the future. There’s a Salvador Dali surrealist quality to some of his work.

Molly Maine's paintings draw on The Decameron, Charles Darwin, La Primavera, and the Unicorn Tapestries in their depictions of ghostly figures surrounded by circles of flowers and bones.

What response have you received to the fellowship program and to supporting artists directly? Have you been questioned much?

Furlotti: The response we get is: "we need more people like you doing what you do." People think it’s unbelievable. I do know that other philanthropists in the community think it’s risky to directly support artists. So they’ve been in shock of what Calligram’s done, but hopefully the show shows that [the artists] are successful.

Byock: There’s a lot of research in philanthropy that goes into risk management. For us, if even one in ten runs off or doesn’t meet the guidelines, that’s less waste than the bureaucracy of us trying to deal with hundreds of proposals, board meetings, etc. We’ve basically kept all the money going to the arts.

What’s next? Will you be announcing a new round of fellows this year?

Byock: We’re finalizing details. Unfortunately we won’t be able to work with the Falcon again because it’s not a nonprofit entity, but we will announce in January about where we’re going. It will be larger, more dynamic, and not focused on oil.

Stayed tuned for that announcement. Last year's fellow are showing a one-night group exhibition this Saturday, January 12, at 1300 NW Northrup Street from 7–11 pm.