Q&A: Kyle Alvarez on Being the First to Direct a David Sedaris Story

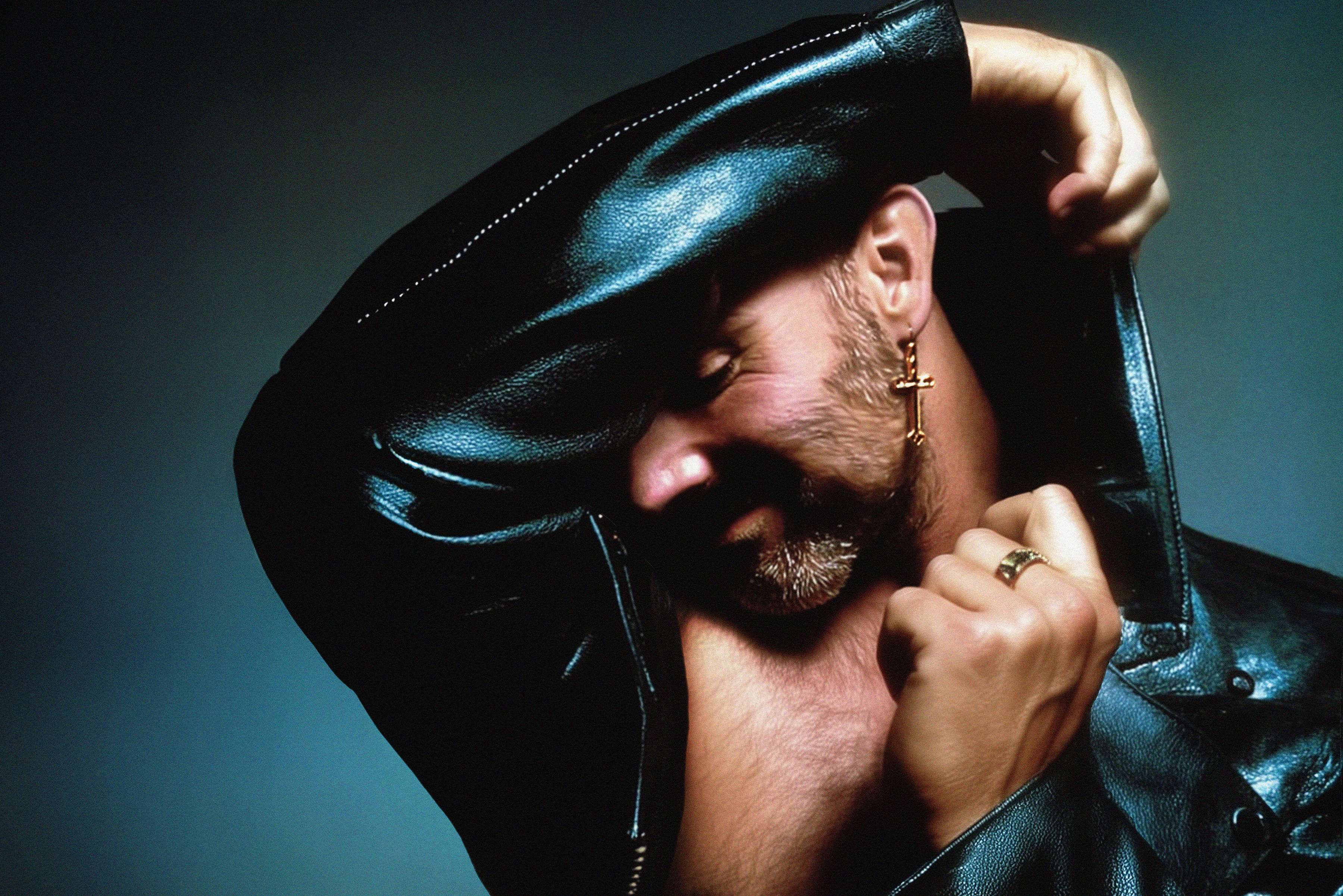

Jonathan Groff in C.O.G.

Image: Courtesy Screen Media Films

Before meeting Kyle Patrick Alvarez, David Sedaris had rejected every movie proposal that came his way. But after viewing the director's first feature, Easier With Practice, Sedaris gave Alvarez his blessing to adapt C.O.G., a short story first published in the 1997 collection of essays, Naked. The movie premiered at this year's Sundance Film Festival, playing to an eager crowd that included Sedaris himself.

C.O.G. recounts Sedaris' post-college journey to experience the "real world" by working on an Oregon apple farm. The film retains Sedaris’ trademark dry wit as a young Sedaris, played by Jonathan Groff [Glee], flounders in an unfamiliar world of manual labor and religious devotion. The movie was filmed on location around Portland, and Oregonians will delight in the familiar foggy landscapes and verdant vistas.

Culturephile caught up with Alvarez to learn exactly how he managed to be the first director to woo the infamously secluded Sedaris, sign on the actors, and convince Hollywood to let him keep the ending ambiguous:

When did you first read C.O.G? What stuck with you about it?

Yeah, absolutely. When I first read it, I was 15 years old. I had started reading David’s work and the story stuck out to me from everything he’d written because it wasn’t, I mean, it was funny, but at the same time, it had this sort of thematic undercurrent that I could really appreciate at the time, which was this conflict between religion and sexuality. There was a certain amount of angst there that I really related to, and so the story just sort of always stuck with me because of that.

Alright, I know you get this a lot, but we have to know: how’d you managed to be the first person to get the film rights to a David Sedaris story?

I would always talk about how I thought it would make a good movie. I would never be like, “Oh, they need to make a David Sedaris movie,” I always thought, “Oh, this story of his seems like it would work really well on screen.” [Sedaris] had a long history of saying no to projects, so I certainly wasn’t naïve about it, but I felt my approach was going to be different. Which was to say, I wasn’t trying to go and make a David Sedaris movie. I was going to try to make a movie out of C.O.G. And I think that sort of thinking was fundamentally different from anyone who had approached him before.

So, long story short, after about a year or so of trying to reach him, I just went to one of his book readings, and I gave him a copy of my first film, called Easier with Practice, and I just said, “If you have a chance to watch it, and if you like it, I’d love to talk some about some about the ideas I have.” Fortunately, I got an email back from him a few months later that he’d really liked the film and was curious about what it was about this story. I think once he heard it was C.O.G., I think it might have piqued some curiosity, because it’s so different from anything else he’s really written.

Did you have the opportunity to run this by David before you shot, or did he want to stay out of it?

My whole pitch was sort of, “Oh, hey, this is going to be its own thing.” So his approach to me was, “Well, if that’s going to be the case, then I don’t want any kind of approval. I think you should go do it the way you want to do it.” Which was, of course, scary, because you want him to like the work and know what it’s up to. But really, he just trusted me to go and make the film that I said I was going to make. So I’m really grateful for that.

And I believe he first saw the finished film at the Sundance premiere?

Yes, that wasn’t the first time I offered. But he was like, “I’ll get to see it with great audio.” It was nerve wracking to wait for his reaction. I was already nervous just about premiering the movie, nevertheless in front of him. But he responded really well to it. I wouldn’t even know how to respond to something like that. If anyone ever made a story where I was a character in it, I would never want to see it. It would be too reflective, it would be, what if it was too real?

So I didn’t know how he was going to react, but I was really grateful that he’s been so supportive of it. And in fact, one of the things he said during the Q&A afterwards was just how real the movie felt to him, and that it reminded him of when he was young. And I wasn’t even aiming for that. So there was something truthful in it that satisfies me and makes me happy.

The film takes place in Oregon and was filmed around the Portland area in places like Hood River and Sauvie Island. Tell us about the experience of shooting in Oregon?

It was great. I wrote it to shoot there—I really wanted to. We were struggling to get the film financed, and at one point there was a financier in Ohio who was interested, but we would have to go shoot it there. And I started looking up photos and doing research, and I really wanted to make the film, so I was sort of convincing myself that we were going to be able to make Ohio look like Oregon, and I kind of lied to myself. Eventually it ended up working out that we could go shoot in Oregon, and I wrote David telling him how excited I was. And he said, “I’m so glad, because Oregon makes such a better Oregon than Ohio does.” And it was such a simple obvious statement, but you get lost, you know, the filmmaker, in your desire to see the film get made. I came so close to not shooting there. And I think the movie would have been ruined.

Aesthetically, we’ve got everything we wanted, locations-wise. The vistas were beautiful. We had all the apple orchards. We were scouting the places David Sedaris was actually in, up in Hood River. And then on the other side of it, the quality of the crew and the support from the state—it would have been impossible to not have the quality of crew that we did, who had experience and who knew what they were doing on a smaller movie like this. Finally, and most importantly, it was just about the sort of feeling it brought to the movie. The kind of people you meet and the kind of places you go to, creatively, that becomes sort of inspiring. You do your best to try to have the world of the movie become another character in the film. So none of those things would have happened had we not shot there.

C.O.G.

Hollywood Theatre

Opens Oct 4

The film takes place in Oregon and was filmed around the Portland area in places like Hood River and Sauvie Island. Tell us about the experience of shooting in Oregon?

It was great. I wrote it to shoot there—I really wanted to. We were struggling to get the film financed, and at one point there was a financier in Ohio who was interested, but we would have to go shoot it there. And I started looking up photos and doing research, and I really wanted to make the film, so I was sort of convincing myself that we were going to be able to make Ohio look like Oregon, and I kind of lied to myself. Eventually it ended up working out that we could go shoot in Oregon, and I wrote David telling him how excited I was. And he said, “I’m so glad, because Oregon makes such a better Oregon than Ohio does.” And it was such a simple obvious statement, but you get lost, you know, the filmmaker, in your desire to see the film get made. I came so close to not shooting there. And I think the movie would have been ruined.

Your film stars Denis O’Hare [True Blood, American Horror Story] and Jonathan Groff. Did you have a hard time getting them to sign on, or were they attracted to Sedaris’ name?

One of the reasons the financing took some time was because I really wanted to fight for the ability to cast the actors I really wanted. We didn’t do any auditions. We just sent the script out to the actors I thought would fit the part. Getting them to read it the first time, I’m sure the Sedaris thing helped. But it was so different than my first time, because I had a film under my belt already, so I also had context. They could say, “Oh, well, here’s another movie he did,” and look at it and sort of get it.

When I was in film school, one thing that was hammered into me over and over again was that you should continually be raising the stakes. I was wondering what you thought the stakes were in the film, and what the protagonist stands to lose.

Yeah, the movie probably broke every film school rule I ever learned.

That’s why I liked it!

There’s no resolution. The structure is very fractured. I think the stakes are his vulnerability. I think he starts off so hardened and unlikeable. My goal was—without even realizing it—you start seeing him become self-aware and vulnerable. The more the movie passes, the more susceptible he is to be damaged, or to become better. I felt like that was the stakes: is he going to break under the pressure of all these different types of people?

A lot of what happens in C.O.G. is left open to interpretation. Hollywood is often reluctant to let viewers draw their own conclusions; they tend to hammer home what the meaning is. Was it was difficult to convince others that it’s okay to leave certain things unsaid and ambiguous?

I was fighting for that ending up until a couple months ago. That’s one of the reasons why it took three years to get made. Everyone was like, “Well, what does he learn? What does he gain?” It’s strange: people talk about ambiguity in so many different ways. I see ambiguity being like, a murder mystery where you don’t find out who the murderer is. But I think what it is, is just, the resolve of the character isn’t very clear. Both my films have been that way. I feel like the only duty the storyteller has is to say, “Hey, this person is different than he was at the beginning.” I think if you go and you watch the last scene of the movie and the first scene, you can see how wildly different of a person he is.

That’s a difficult thing and you’re asking a lot of an audience. You’re also inviting a lot of criticism from people being like, “Your movie had no point.” You have to say, “Okay, I made this movie for the people who are going to respond to it, and they’re really going to respond well, and the people who aren’t, aren’t.” And that’s okay. At the end of the day, I’d much rather make a movie that people respond to in any which way than a movie that you forget you even watched a few minutes later. The best thing I ever hear is, “We went afterwards for a drink and we just talked about the movie for an hour.” Even if the movie has some mistakes, if a movie does that to you, and you’re still talking about it an hour later, I think that’s the best kind of movie-going experience for me.