Tending Tradition at the Portland Japanese Garden

Since taking the helm in 2005, garden CEO Steve Bloom has overseen rapid growth.

With his orange-and-yellow floral shirt and balsa-smooth pate, Bloom shimmers as brightly as the fish swimming in the garden’s waterfall-fed pond. “I’m in love with the new koi,” he lilts in inflections that could cause a cat to purr. “They each have their own personality. Some are aloof. Some are friendly.”

The koi swim in water cleansed by a $252,000 filtration system Bloom raised the money for. Their care will be overseen through a new partnership he forged with the Hatfield Marine Science Center. And with a name-that-fish fundraising campaign, they will net $2,500 to $5,000 apiece.

Dressed in Smokey Bear beige, Uchiyama calmly frets about the garden’s tallest problems: several western red cedars. Towering 100 feet, their burly branches slow the advance of everything in their fat shadows and, in the garden’s delicate aesthetics, make their surroundings feel puny. “As they grow,” he says, “the garden’s proportions will shrink.”

Compared to Bloom’s quick-turnaround campaigns, Uchiyama takes a more patient approach to the riddle of the cedars. Topping the trees would yield a utility-company-style haircut, he says. Chopping them down in tree-hugging Portland could trigger protests. Instead, Uchiyama has planted more prunable hemlocks next to the cedars. Many years in the future, when the new trees grow large enough, the older ones will slowly, quietly disappear.

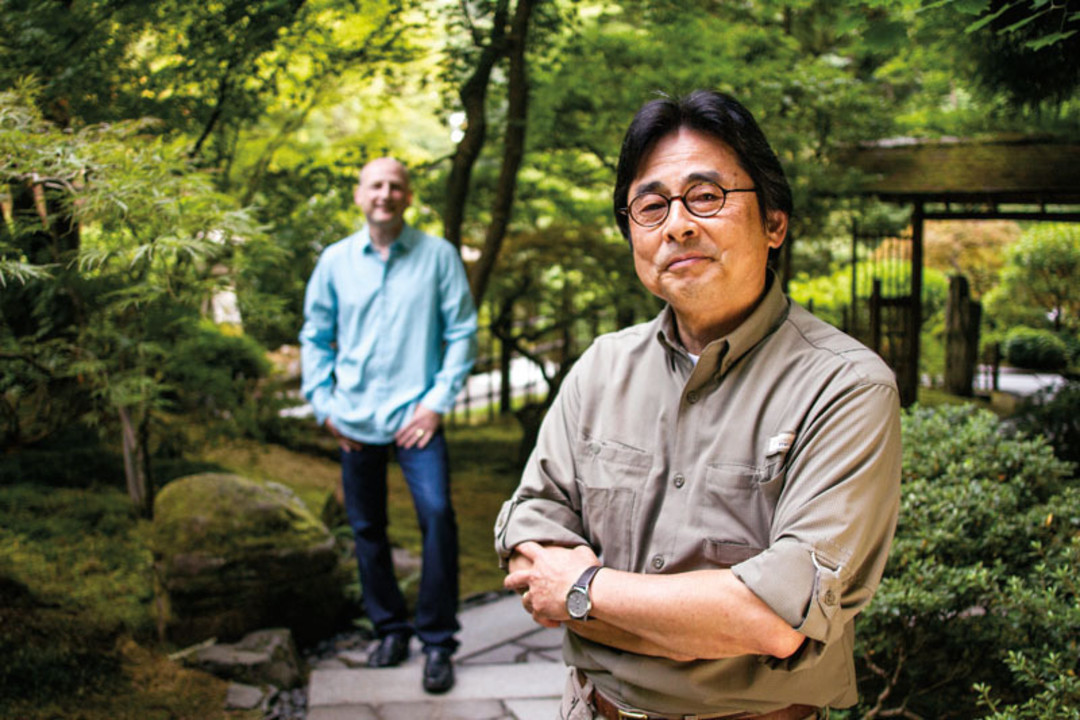

As they walk through the verdant, 5.5-acre compound in the West Hills, the two men responsible for stewarding one of the most historically and aesthetically significant Japanese gardens outside Japan each combine yin’s feminine, contemplative qualities with yang’s masculine drive, if in differing ratios. But they’ve found their own cosmic unity in a goal: to turn this hillside, with its meditatively cultivated plants and postcard views of the city and Mount Hood, into the Japanese garden that reinvents Japanese gardening. Their mission is not only for the US, where many gardens are volunteer-run, but for Japan itself, where interest is waning as the population ages and shrinks.

“We’ve been at the forefront of positioning Japanese gardening as an art form,” Bloom says. “In Japan, their young people are not learning the culture of gardening. So we need to look to new models.”

Celebrating its 50th anniversary this month, the garden, as any regular visitor knows, has never looked better. Since taking their roles eight and five years ago, respectively, Bloom and Uchiyama have overseen dramatic growth. Funding has rocketed from $39,000 to $1.1 million annually, covering significant renovations and staff expansions. Membership has doubled; this year, garden attendance is projected to approach a new high of 300,000. And on October 19, at the anniversary gala, many garden supporters hope that Bloom will go public with a so-far “quiet” capital campaign for a new entry gate and a “Cultural Village” of classrooms, offices, library, gallery, and tearoom designed by the renowned Japanese architect Kengo Kuma. A “starchitect” across the Pacific, Kuma has yet to complete a major commission in the US. The Portland project will resonate in his home country, as it will house the new International Institute of Japanese Garden Arts and Culture, devoted to developing programs to keep garden arts healthy and relevant in the 21st century.

“The only way to train as a gardener has been to speak Japanese, live in Japan, and work under a master for five years,” Uchiyama says. “The other option is to buy a Japanese garden book and read it. Our goal is to make this place a hub for teaching in a uniquely Portland way.”

Third-generation gardener Sadafumi Uchiyama wants Portland’s garden to become a hub for education.

Image: Ashley Anderson

In the twelve-century history of Japanese gardens, Portland’s is a toddler. But it has also been a trailblazer from the moment it opened as the first traditional garden to be built outside of Japan after World War II, thanks to a sister-city relationship. Despite initial tensions that led to the tagging of the then-director’s trailer with “Go Home Jap,” many Portlanders saw the garden as a cultural salve and business asset. Planned by master designer Takuma Tono and developed by a succession of young, talented Japanese directors over 20 years, it is widely considered to be the most authentic garden outside Japan.

It is also uniquely “public,” according to Makoto Suzuki, a leading scholar of Japanese gardens at the Tokyo University of Agriculture. In Japan, he says, large-scale gardens have long been created by monks, nobles, rich men, and, in modern times, governments. In contrast, private patrons and volunteers built Portland’s garden on a former chunk of the Oregon Zoo. They funded construction, laid the Belgian block salvaged from Portland’s old cobblestone streets, and donated fully grown trees from their yards and nurseries.

But as maintenance budgets failed to keep up with attendance, the garden needed to reach beyond its grassroots governance, according to longtime board member Dee Ross. “We weren’t using the word ‘global’ to describe our ambitions at that time,” she says, “but we wanted it to survive.” Enter Bloom and Uchiyama—not surprisingly, through very different doors. Bloom arrived via a national search, with leadership and fundraising skills honed in the distant world of classical music. (The Buffalo, New York, native ran the Honolulu and Tacoma symphonies.) Uchiyama, a third-generation gardener from Japan who also studied landscape architecture in the US, began as a volunteer. But he quickly rose to board member and then, at Bloom’s and the rest of the board’s urging, to paid curator.

“They’re very similar, even if the differences on the outside look like night and day,” Ross says. “Their dedication to being the best is identical.”

For each, that meant envisioning a larger global role for the garden. The idea of creating a teaching institute arose in the late 1990s with the help of a “white paper” by then-volunteer Uchiyama. In 2008, Bloom developed the idea further during a six-month fellowship in Japan, mapping out a center focused on teaching gardening and its related arts: ichibana (flower arrangement), tea, calligraphy, and bonsai. In addition, Portland’s garden spearheaded the creation of the North American Japanese Garden Association, devoted to sustaining and expanding the tradition. The efforts helped Bloom convince Japan to give its own citizens a tax write-off for donating to Portland’s garden, making it the second organization outside the country ever to earn such status.

In June, Bloom orchestrated an exclusive VIP event in Tokyo hosted by Tadashi and Teruyo Yanai, Japan’s richest couple (Tadashi is CEO of clothing chain Uniqlo), and shining with CEOs, ambassadors, and royalty. The event was social, but the aim was clear: that Japanese donors might help—substantially—in building Kengo Kuma’s village, a project for which early estimates reached well into the millions.

As he sits in the place in the garden he says most reminds him of Japan—the Azumaya Shelter overlooking a mossy hillside—Bloom reflects, “Whenever you enter a project like this, there’s a degree of confidence, but there’s a degree of unknown. So you hustle on the sheer force of will that you’re going to make it happen.”

Pondering some Portland Water Bureau–owned trees in the distance that have grown up to block the garden’s once-clear vistas of the city, Uchiyama offers an analogy for the relationship of Portland’s garden to the tradition’s country of origin. Sometimes, he suggests, a child needs help from someone beyond his or her parents. “Japan brought the garden form to a point, but it may not be the right country to bring that form to the next level,” he says. “We are not Japan. So that entitles us to do something new. We are working with the mother to evolve this child.”