Live Wire Radio Goes for National Glory

Image: William Anthony

Just hours before Live Wire's October 19 show at the Alberta Rose Theatre, Courtenay Hameister, the show's head writer, hunkers down in the green room with staff writer Jason Rouse. The pair gleefully—if frantically—write the final version of a quiz segment for the weekly variety show.

The concept: a trivia quiz that will pit prominent comic book artist Brian Michael Bendis against a self-proclaimed “superfan.” The twist: unbeknownst to Bendis, his wife leaked Hameister personal information to weave into the questions.

“We start with basic stuff,” Hameister tells Rouse. Both writers wear chunky black cardigans, suggesting the married couple they often act like, but aren’t. “Then we can start asking the creepy stuff: he has all his T-shirts organized in labeled cubbies—name two of the six labels. Is that creepy?”

“It would be creepy,” Rouse answers, “if we say Bendis has six drawers in his bedroom, and the superfan says, ‘They’re not drawers, they’re cubbies.’”

It’s the kind of twist—destined to catapult a simple interview into an unpredictable, real-time moment—that propelled Live Wire from a low-budget Portland culture mash-up into something bold, new, and increasingly national. Branding itself as a bright problem child of the public-radio world, with taglines like “Live Wire: radio variety for the ADD generation,” the show packs the Alberta Rose twice a month and now airs on 40 stations around the country (and in England).

“We want to give more than just an hour of entertainment,” says executive director Robyn Tenenbaum. “It’s about crafting a journey with something to chew on, something to laugh at, something to pause at. We want guests who cause us to think differently.”

Live Wire’s climb from DIY obscurity comes at an auspicious moment, as the public-

radio world nervously anticipates a once-in-a-generation vacancy. In 2011, Garrison Keillor, the gravelly voiced radio demigod whose A Prairie Home Companion has dominated the public airwaves since 1974, announced that he would retire in 2013. While the 71-year-old later recanted the threat to raze Lake Wobegon, his flirtation with abdication put stations on alert. Live Wire is heard by about 80,000 people each week. Keillor’s show draws four million weekly listeners across 600 stations, forming a holy trinity with Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me and Car Talk as public radio’s biggest entertainment draws—and, consequently, biggest pledge-drive fundraisers.

Live Wire Taglines

The race is on to find the next big thing (tempered with the proper NPR earnestness, of course). Live Wire is among a handful of upstart shows jockeying for Keillor’s variety kingdom. The station that Keillor built, Minnesota Public Radio, touts Wits, a comedy- and music-focused jaunt. National Public Radio itself backs Ask Me Another, a Brooklyn-based variety quiz show. South Dakota’s Rock Garden attempts an unlikely combination of music and, yes, gardening.

“As much as I don’t believe we are like A Prairie Home Companion, we are the replacement,” says Hameister. To her, that means a show that’s younger, hipper, and more modern—basically, a Portland-infused generational successor to PHC’s boomer-beloved folksiness.

As showtime nears on the night of the 19th, that approach feels like a torrid romance between calculation and chaos. Hameister is handing out the new quiz. The first guest band waltzes in minutes before the show is supposed to start. And Luke Burbank, the show’s new host (and a regular on Wait Wait and CBS Sunday Morning), has just flown in from Los Angeles with some not-so-good news: somebody stole his laptop at the airport—while, he bemoans, he was buying an $11 packet of beef jerky.

“It had all my notes for the show on it,” he tells anyone who will listen. “At least I got a monologue out of it.”

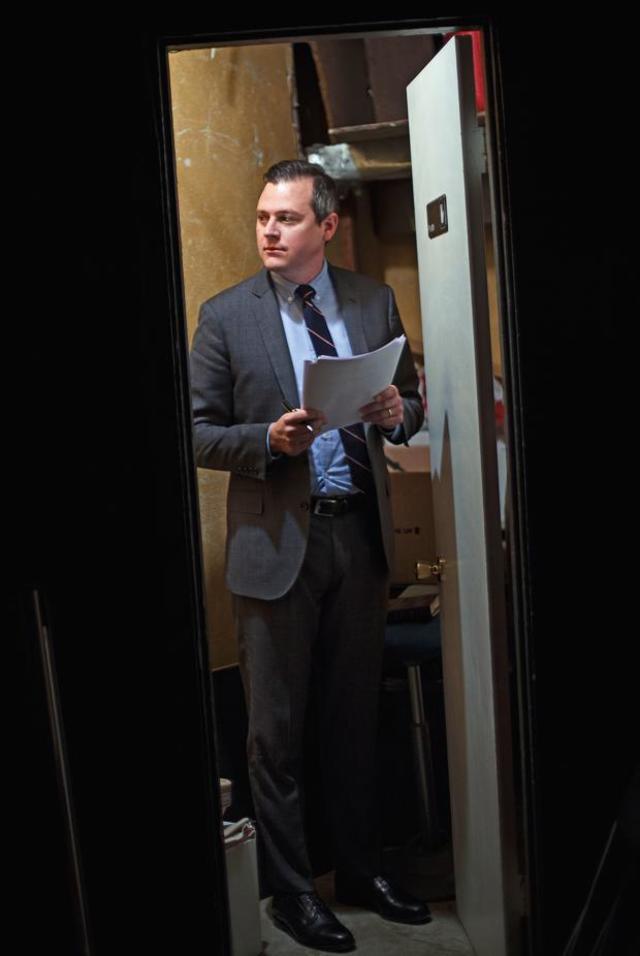

As Burbank retreats to the tiny storage closet that doubles as his preshow office to salvage his thoughts, two solid weeks of methodical preparation somehow comes down to a scramble. Burbank’s boyish, gap-toothed grin almost convinces that the mayhem is completely worth it. And maybe it is. As a look back on the making of this evening’s Live Wire production reveals, great radio is anything but an exact science.

Tuesday, October 8: The Pitch

Luke Burbank in his backstage closet/office

Image: Sierra Breshears

A weekly radio program is an insatiable beast. Every two weeks, Live Wire mounts a Saturday-night performance at the Alberta Rose, complete with multiple guest interviews and readings, two musical acts, sketches, and various trademark jetsam like “Dear Live Wire,” a segment in which actors and guests make up answers to absurd audience questions. The recording then gets edited into two hour-long radio episodes that broadcast from Portland to Pittsburgh.

The Tuesday after an October 5 taping, Hameister, Rouse, and three others filter into the cramped writers’ room in their N Mississippi Avenue office to begin anew. Each of the show’s writers must present 10 concepts for sketches. Outlandish ideas and playful interjections soon build like improv riffs in a veteran jazz ensemble.

“A guy’s going through a Breaking Bad withdrawal,” suggests show veteran Sean McGrath. “I don’t know if he’s just depressed, or if it’s like a heroin withdrawal.”

“What would be the methadone for Breaking Bad?” asks Hameister.

“Sons of Anarchy,” Rouse shouts. “It’s gritty.” And thus pop culture–infused radio comedy is born. Over four meetings in the next 11 days, writers turn the best pitches into full sketches. (By the time the Breaking Bad skit hits the stage, it features an interventionist prescribing lost episodes of Doctor Who recently discovered at a Kenyan radio station.)

This process has acquired considerable polish since Tenenbaum and Kate Sokoloff started Live Wirein 2003, with Hameister as head writer and Jim Brunberg as Technical Producer. (Sokoloff left in 2011.) They produced their first monthly show for OPB in March 2004. Everything was ad hoc, including when Hameister took over as host after just four shows, with no experience. But audiences packed the house and local celebrities, like director Todd Haynes, joined as guests from early on. Within a year, the local press declared Live Wire on the verge of countrywide distribution, already describing it as A Prairie Home Companion for a younger generation.

“We were optimistic,” admits Tenenbaum, a wiry woman who crackles with energy, about the founding ensemble’s belief that the show could attract a national following in just a year or two. “But we did know we couldn’t go national without a weekly show.”

As the production evolved into a small company—with an annual budget of $350,000, Live Wire now employs five mostly full-timers and a half-dozen contractors—they finally nailed the formula in 2010: two live shows per month equals four broadcast episodes. Soon after, Live Wire began airing in regional markets like West Marin, California, and significant cities such as Austin and Indianapolis, with public-radio affiliate stations paying the production company for episodes. As the show’s reputation rose, so did the prestige of its guests, often national writers, bands, or film directors passing through Portland.

“They’ve really tightened up the show, and have a better understanding of what a nationally distributed show should sound like,” says Todd Bachmann, a radio veteran of This American Life and Sound Opinions who advised Live Wire on its national push.

Or as a sign in the writers’ room declares: “Get in. Be funny. And get the hell out.”

Wednesday, October 9: Passing the Mic

Live Wire host Luke Burbank and head writer Courtenay Hameister

Image: William Anthony

The day after the pitch meeting, Hameister and Tenenbaum talk to Burbank via Skype. The 37-year-old host, who lives in Seattle, has a much higher profile in public-radio circles than the rest of Live Wire’s staff—and a spiky reputation, in that well-behaved world, as an iconoclast.

Starting as a show booker at the Seattle public radio station KUOW in 2001, Burbank worked his way up to reporting for NPR, then to hosting programs. First, he filled in for Peter Sagal on Wait Wait...Don’t Tell Me (and continues to appear regularly). He cohosted a short-lived, New York–based NPR news show, The Bryant Park Project, devised to appeal to younger audiences. Just a month after the program debuted, Burbank quit, saying he wanted to be closer to his daughter in Seattle. (He later acknowledged clashes with NPR executives.) The abrupt departure made him persona non grata at NPR for a time, though he gradually won his way back into the operation’s good graces. Meanwhile, he embarked on commercial radio stints in Seattle and his own podcast, Too Beautiful to Live, which clocks two million downloads a month. Through it all, Burbank developed a reputation for out-of-the-box hosting strategies, such as challenging Republican presidential hopeful Mike Huckabee to Ping-Pong.

“He’s funny, he’s fast, he’s interesting, and he’s fearless about putting himself out there,” Sagal told the Seattle Times in a profile of Burbank. “He’s also one of those people, I think, who is able to be genuine in a very artificial environment.”

Burbank’s role at Live Wire evolved rather quickly. Tenenbaum and Hameister had booked him for last year’s March 16 show, in part to feel him out as a potential backup host. Then at 9:30 p.m. on March 15, Hameister left Tenenbaum the message every producer dreads: she could not go on. The pressure of working as both head writer and host had sparked a full-scale panic attack. (She would eventually have gall bladder surgery for a stress–related condition.) Hameister’s solution: ask Burbank to host the show.

After a night of drinking with friends, Burbank awoke to a hangover and multiple calls from Tenenbaum. Though he was slated to be a guest, he’d never actually heard a Live Wire episode—but he didn’t hesitate. “That show was a complete blur,” he recalls. “I was trying to act like I was not nervous because I could tell everyone else was freaked out. It was a complete act.”

Act or not, it worked. Hameister permanently relinquished her role to Burbank, and he quit his commercial show. “Everything I didn’t love about my day job, I loved about Live Wire: the crowd, the things they talked about, the staff,” he says. “It did mean taking a vow of poverty, but I think that Live Wire has the potential to be one of the significant shows on public radio that everybody listens to.”

Over Skype, Tenenbaum and Hameister suggest that Burbank—who recently grilled Congressman Earl Blumenauer, a pot-legalization advocate, on exactly which marijuana expenses should be tax deductible—quiz Bendis, the comic book creator, on superheroes. Burbank offers a different idea: the quiz competition between Bendis and a fan. “And we should sandbag him,” Burbank adds with a devilish grin. “It’ll be funnier if he loses.”

Saturday, October 19: The Show

While Hameister was a writer-host, more comfortable reading crafted essays than performing off the cuff, Burbank is a showman. He bounds on stage in a gray suit and slicked-back hair, takes the mic, and leans on the stand with the sly confidence of a Rat Pack icon. With only an outline in mind, he launches into the story of losing his laptop and how it also meant losing irreplaceable photos of his daughter.

His hosting style is unabashedly confessional—equal parts self-indulgence and self-deprecation—and his quick humor threatens to steal conversations from any less-than-nimble guest. Burbank is a public-radio deviant, as interested in pop culture, sports, gambling, and drinking (during one brunch interview, he makes it through two Jamesons and a Ketel and soda) as foreign affairs or health policy.

After an excerpt from an Elliott Smith song, Burbank conducts an interview with William Todd Schultz, the author of Torment Saint: The Life of Elliott Smith. “I want to ask you a question, and in the green room you said you didn’t want me to ask this question,” Burbank says. “I remember hearing that there were questions about how he died.”

“There’s a small, monomaniacal set of fans who are convinced that Elliott Smith was murdered,” answers Schultz. “Those people are now essentially attacking me.”

“Your next book is about Tupac, right?” pokes Burbank, as the audience erupts in laughter.

“You’re good,” Schultz replies. “You’re very good.”

Then Burbank, a die-hard Smith fan, pivots to a respectfully somber tone, and the segment ends with a heart-wrenching live performance of Smith’s “Between the Bars” by Suzanne Tufan.

“The part of Burbank’s brain that handles radio interviewing and hosting is like Adonis’s washboard stomach,” says Bachmann. “He commands the stage, and he’s really funny.”

All agree that Burbank has shaken up Live Wire’s creative strategies. He helped introduce live phone interviews to the show, recently dialing a taxidermist in Alabama to discuss whether kittens could have wings. He’s also mixing postproduction content into the broadcast episodes. After the karaoke staple “Baby Got Back” came up in a live interview, for instance, he called Sir Mix-A-Lot to tape an interview, which was edited into the program before it aired.

“It was already a good show, but it’s going to the next level with Luke, and I think there’s even a next level,” says Jeff Hansen, the program director of Seattle’s KUOW, which is negotiating with Live Wire to expand to represent the entire Pacific Northwest, including occasional recording sessions in Seattle. That sense of place, Hansen argues, could echo Keillor’s intense identification with the Upper Midwest.

Bendis is the final guest of the night. He floats through his interview like one of his superheroes. But then comes Burbank’s coup de grace: the quiz. The superfan beats Bendis on a number of comic factoids, to Bendis’s chagrin. But he looks truly shocked as the questions move into material only a spouse or stalker would know. The audience squirms with laughter.

The moment crystallizes Live Wire’s arc. What started out as an entertainment show 10 years ago has become an audio adventure that travels from hilarious absurdity to intense emotion and back in the course of an hour. Other public-radio shows might interview Bendis. They probably wouldn’t challenge him to a quiz, then cheat.

“Instead of being the next Prairie Home Companion, I want to be something that never existed before,” Burbank says. “I want the show to have more warts—sometimes it’s awkward; sometimes we mess up. I want to create something that’s much more of a journey for people: they don’t know where it’s going to go.”