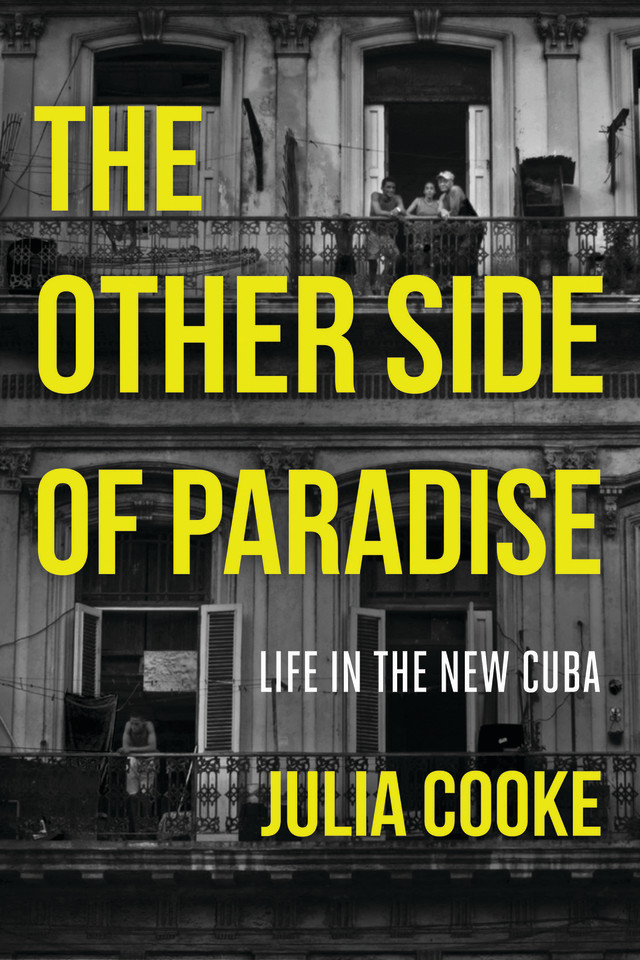

The Other Side of Paradise: Life in the New Cuba

We’re so proud when one of our interns goes on to something big. Julia Cooke interned with us the summer of 2005. Shortly thereafter, she headed for Mexico City and then Cuba, bouncing between the two for five years to report stories that ranged from buying gourmet food on Havana's black market to Mexico City's first and only sex-industry trade fair.

Now she’s turned her experience with the youth of post-Fidel Havana into her debut book, The Other Side of Paradise: Life in the New Cuba. As you can see from an excerpt from the intro below, some liked to salsa while others preferred to headbang in dilapidated amphitheaters, but all defied the clichés.

Cooke reads at Powell’s on Hawthorne on April 10 at 7:30 pm.

I started to learn Cuban history when I enrolled in a University of Havana class called “History of Cuban-U.S. Relations, 1901–1959.” I’d taken a semester off from college to study in Havana in 2004, but on my first day, I’d understood startlingly little of the rapid-fire Cuban Spanish as I sat at the front of a classroom of thoughtful twenty-year-olds who smoked cheap, unfiltered Criollo cigarettes from wrinkled paper packets in the hallways between classes. The chairs were made of dented metal and pressed plastic and bright sunlight flecked the floors with the imprints of the trees outside the open windows. The ceilings peeled, every student took assiduous notes on thin paper pads, and the only word I distinctly heard was enmienda, repeated over and over. So after class, I walked to a bookstore and found a middle-school history textbook. Later that night I flipped through page after page of illustrations and captions: “Workers were poor, illiterate, and miserable before the triumph of the revolution,” “during the neocolonialist rule of the United States before 1959,” “then cheering people greeted the guerrilla fighters,” and “we love Comandante Fidel.”

Enmienda, I learned, referred to the Platt Amendment, the 1901 American resolution to withdraw the remaining yanqui troops occupying Cuba after the Spanish-American War and establish the U.S. government’s right to intervene in Cuban politics, turning it into a self-governing colony. But in that moment, the fluorescent lights—an initiative to replace all of the country’s incandescent bulbs with energy-efficient Chinese models—hummed overhead, and I thought, Every single young person that I will meet has read this textbook.

Everyone my age sat under the same lightbulbs and had read the same book and I was hooked: Not only was Havana romantic and steeped in drama and history and humor, but it was inexplicable and strange and split from every cliché I’d heard or read about the city. Because the fact was, there was tremendous diversity, rebellion, and sophistication among the young people I met, both while studying at the University of Havana and on visits and reporting trips in the years to come. Some danced salsa sinuously, though they couldn’t afford to go to concerts at the Casa de la Música, the city’s main tourist venue for salsa and casino. Others preferred to headbang in dilapidated amphitheaters on the outskirts of town among self-described anarchists. Everyone wore jeans, not the threadbare Lycra shorts that news stories had cited. None of them drove old cars or could pay for rides in the glossy well-maintained Chevys that gleamed through the streets. They, and I, rode in 10-peso gypsy cabs or, more often, in packed buses on commutes that felt like being slurped up through a drinking straw, pushed toward the back by sheer momentum, and spat out only after hollering “Chofe, this is my stop!” and elbowing toward the door.

Months after trust had built around study sessions and then drunken evenings and then political debates, I saw that the Cubans I knew passed around frayed copies of People or Spanish political rags, USBs loaded with Portishead or Daddy Yankee, carefully preserved copies of The Unbearable Lightness of Being between brown paper covers for discretion. I heard the complaints of a recent college graduate, my history instructor, Yoel, who for his lack of ideological zeal had been denied a job in international relations and was assigned to teach teenagers instead. His class held overt disapproval of U.S. neo-imperialist foreign policy and an oblique yet critical analysis of Cuba’s one-party system. In the four years after I’d studied in Cuba, I moved to Mexico City, began to work as a journalist, and took a few reporting trips to Havana. When I searched for him on one such visit, he’d disappeared.

The email address he’d given me bounced my letters back and no one at the university knew his whereabouts.