PDX Theater's Irish Spring

Irish theater for the win at Artists Rep's The Playboy of the Western World.

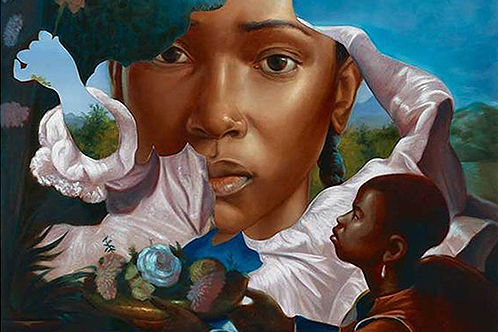

Image: Owen Carey

Ireland isn’t a big place, but it casts quite the literary shadow. Celebrated for its novelists, poets, and playwrights, the island nation has a knack for producing writers with a keen eye for heart-wrenching tragedy, witty satire, and wry self-criticism.

The Portland theater scene seems to have collectively turned its eye to the Emerald Isle this spring, as four Irish plays open in the next month around town: Artists Repertory Theatre’s The Playboy of the Western World, Third Rail’s The Beauty Queen of Leenane, Corrib’s The Hen Night Epiphany, and the touring Broadway production of Once. That’s a lot of craic to take in, and if you’re feeling a bit out of your depth, here are a few things to know about Irish theatrical tradition to help you make sense of it all.

1) Irish Theater has a lot to say about Irish identity.

There was no national theater in Ireland until the turn of the 20th Century and the establishment of the Abbey Theatre in Dublin, one of the many visible signs of the swelling of nationalist sentiment in Ireland that culminated in independence from Britain. It’s not much of a surprise, then, that Irish identity has been and continues to be a central concern of the nation’s theatre ever since. The four plays premiering over the next month, which were debuted over a span of 104 years (from 1907 to 2011), are no exception. After all, Ireland asserted its independence less than a century ago—you can forgive a bit of navel-gazing.

2) That identity has often been the source of some disagreement.

John Millington Synge’s The Playboy of the Western World incited riots upon its premiere at the Abbey Theatre in 1907, due to its perceived slight against the Irish peasantry and public morals: the play portrays a tiny coastal town beguiled and impressed by a young stranger’s exciting tale of a murder he committed. Nationalists like Sinn Féin leader Arthur Griffith felt the play undermined their political views, and were wary of someone like Synge, who was of Protestant English ancestry, misrepresenting rural Irishmen (famed Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw is said to have felt similarly).

The Playboy of the Western World

Artists Repertory Theatre

May 20–June 22

Controversial as Playboy was, it set the standard for unapologetic self-examination on Irish stages. “Any Irish playwright after 1907 owes their career to Synge,” says Artist Rep’s dramaturg Sam Hull. “This was the first play that brought international acclaim to the cause of Irish theater.”

It certainly wasn’t the last to court controversy: Seán O'Casey’s The Plough and the Stars (1926) caused similar riots due to its treatment of the independence struggle, provoking W.B. Yeats to famously ask, “Is this to be the recurring celebration of the arrival of Irish genius?”

Jayne Taini, Maureen Porter, and Damon Kupper in Beauty Queen of Leenance

Image: Owen Carey

3) It’s rooted in the country’s relatively rural, isolated history…

The Beauty Queen of Leenane

Third Rail Repertory at the Winningstad Theatre

May 30–June 22

Martin McDonagh’s black comedy The Beauty Queen of Leenane (1996), which wraps up his Leenane Trilogy (Third Rail made its name with the first part, The Lonesome West, in 2006), offers a dark take on rural Irish life not dissimilar to Synge’s, and has (thus far) avoided driving audiences to violence. That’s more than one can say for the characters, though—anyone familiar with McDonagh’s work from films like In Bruges and Seven Psychopaths can testify to the suddenness with which his plots can get bloody. And that’s not the only source of unease in Leenane: the play is set in the eponymous village in Connemara on Ireland’s west coast, and the combination of ‘90s references and rural locale create a bizarre juxtaposition of eras. For some, this has the effect of poking fun at Ireland’s rural history; for others, it might suggest that history isn’t so far away.

Broadway Across America's Once

4) ...But that history is rapidly changing

“Ireland seems to do things in very big jumps—it’s almost as if they skipped over the Industrial Revolution and went straight to the computer age,” says Gemma Whelan, artistic director of Portland’s fledgling Corrib Theatre, a company dedicated to Irish works. Indeed, the three modern Irish plays opening in town are all intimately concerned with the swift pace at which the country is changing.

Take, for example, the wildly popular musical Once, based on a intimate Oscar-winning indie filmed on a miniscule budget: though the story is dominated by its two central characters, an Irish street musician and a Czech girl who finds herself drawn to his music, the city of Dublin plays a crucial, ever-present supporting role. The nameless pair lives in an evolving city whose rapidly changing economy is passing them by. The busker’s ex-girlfriend broke his heart and took a job in London; his new friend supports her mother and daughter by selling flowers.

Once

Keller Auditorium

June 10–15

Though the original film was released in 2007, it’s characters offer a prescient allegory for Ireland both before and after the market crash a year later: a onetime haven for European immigration whose inhabitants are now forced to leave to find work.

The transitions and setbacks of the new Ireland loom similarly over Corrib’s offering, Jimmy Murphy’s The Hen Night Epiphany (2011), which follows five women from contemporary Dublin whose budget bachelorette party leads to some revealing insights about their lot as Irish women.

The Hen Night Epiphany

Corrib Theatre at CoHo Theatre

June 7–29“I’m not sure this play could have been written 30 years ago,” muses Whelan. “Ireland has changed dramatically, and part of that is opening up to Europe.” With economic change comes a broader cultural shift: Whelan notes that an “island culture” of tight-lipped secret-keeping has been blown wide open, in part from clerical abuse scandals and, more recently, those surrounding the incarceration and forced labor of young single mothers in “laundries.” It’s in this more transparent cultural climate that the women in Murphy’s play can talk frankly about gender disparities in Ireland.

“These women are talking about problems that haven’t gone away,” Whelan is quick to point out. What’s changed is openness: in a world in which a tiny film made by friends on the streets of Dublin can spawn a worldwide musical sensation, Irish audiences no longer react with anger towards works like Murphy’s and McDonagh’s (nor Synge’s, for that matter). Part of what led audiences to riot over Playboy of the Western World was the use of the word “shift,” a women’s undergarment similar to a slip. Whelan quips: “There are a lot worse words than slip mentioned in The Hen Night Epiphany!”