How Laika is Revolutionizing Stop-Motion Animation with 'The Boxtrolls'

In the glossy, computer-generated world of Frozen, Toy Story, and Shrek, stop-motion animation, where real-world hands manipulate real-world puppets frame by frame, might seem downright old-fashioned. Not in the hands of Laika. Owned by Phil Knight and situated in two nondescript, sprawling warehouses in Hillsboro, the only major movie studio in the metro area puts stop-motion on the innovative cusp by introducing 3-D printers, cameras, and CGI to the painstaking craft, creating a hybrid at once handmade and high-tech.

Laika’s first two films, Coraline (2009) and ParaNorman (2012), each grossed more than $100 million and received an Oscar nomination for Best Animated Feature. The Boxtrolls, Laika’s third feature, hits screens nationwide September 26, with voices from the likes of Sir Ben Kingsley and Tracy Morgan. The film conjures the studio’s most imaginative realm yet: the decadent, Victorian village of Cheesebridge, where humans live aboveground and garbage-scavenging boxtrolls live below. The $50 million project is the result of 350 people shooting 125,280 individual poses over the course of 18 months.

To kick off our annual Fall Arts Preview, we take a close look behind the camera at the making of The Boxtrolls. Then, we turn the spotlight on the can’t-miss shows, events, and festivals that will define Portland’s cultural agenda this fall.

Building Character

“We really went to town on Winnie,” says Georgina Hayns of the heroine’s hair, which is made from individually dyed strands of hemp. “Her main color is ginger like her father, but then she’s got these fluorescent green stripes that accentuate the illustrative quality.”

Based on Alan Snow’s book Here Be Monsters!, The Boxtrolls slow-cooked in Laika president Travis Knight’s head for 10 years. Attracted by the story’s balance of darkness and light and its Roald Dahl–like cleverness, Knight and his team whittled the book’s 500 pages of multiple plotlines into a story about an orphan named Eggs (voiced by Isaac Hempstead Wright), who is reared by the subterranean, box-clad creatures and must protect them from an evil exterminator named Snatcher (Kingsley).

Whereas Coraline and ParaNorman were set in modern times and used clean lines, colors, and angles, The Boxtrolls draws inspiration from European Expressionism, where swirling colors are edged with contrasting outlines. “We’re creating a turn-of-the-century fantasy, Dickensian world, which is great for stop-motion, because it’s all about detail,” says Georgina Hayns, head of puppet fabrication.

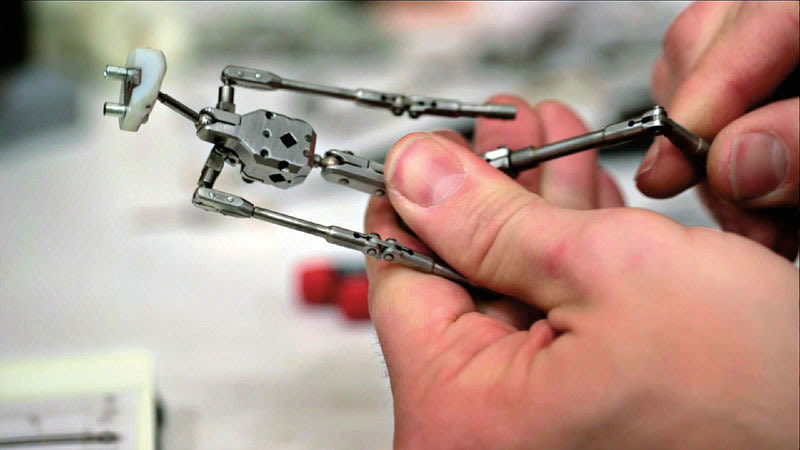

To design a puppet-character like Eggs or his eventual ally Winnie (Elle Fanning), pictured, fabricators sculpt a model based on a conceptual drawing. Accounting for movements the puppet needs to execute, the fabricators then break the sculpture into separate parts and put together an internal skeleton that will allow animators to manipulate the puppet.

Coraline was noted for the characters’ hand-knit clothing. For The Boxtrolls, costume designer Deborah Cook uses an embroidery machine to sew miniature knitwear and lace, looking to Paris’s Ballets Russes, which worked with artists like Marc Chagall and Henri Matisse, for inspiration.

Making Faces

To animate a simple facial expression like a smile—to say nothing of making a character speak—requires dozens of heads with expressions that change slowly each frame. With 24 frames per second, and days of sculpting for each head, expression has always been stop-motion’s biggest challenge.

Until 2005, that is, when Laika sparked a revolution with a new technology: 3-D printing. At the time, most industries primarily used it for prototyping; Laika saw it as a means to mass-production. Whereas The Nightmare Before Christmas was considered a breakthrough in 1993 because the lead character had some 400 different facial expressions, Laika’s protagonists have the capability for more than 1 million.

“These little guys have more emotional range than I will ever have,” says Brian McLean, the studio’s head of rapid prototyping.

Here’s how it works: Computer designers make a 3-D scan of the character’s sculpture to engineer a topographic map of its head. They then use animation software to model each micromovement and apply color. They send files to a printer, which sprays paper-thin layers of resin, like an inkjet going over and over the same area, until it builds up the three-dimensional piece.

Laika’s high volume has pushed the evolution of the still-nascent technology. At first, the printers worked only in monochrome; fabricators had to hand-paint each face for Coraline. By ParaNorman in 2012, the machines could print with basic colors. For Boxtrolls, Laika was able to print shape and color in minute detail.

Cheesebridge’s economy runs on the gooey goodness of fromage; designers produced 55 different types in all shapes and sizes.

Old World Charm

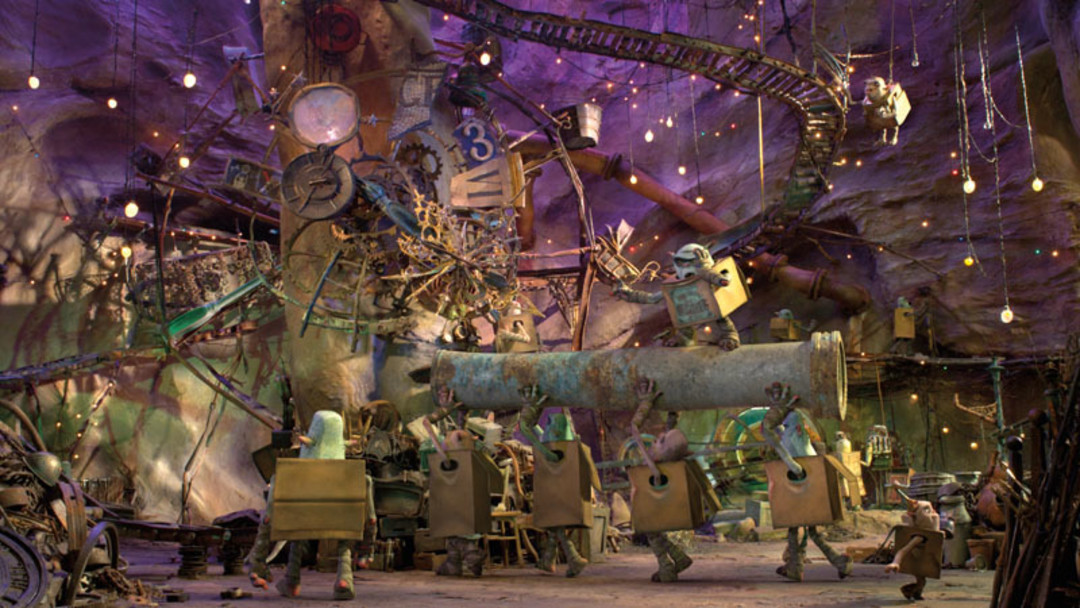

Set in a vaguely Victorian, cheese-loving, pan-European town, The Boxtrolls is Laika’s first period piece. With the wobbly lines and swirling colors of European Expressionism to guide them, the creative team builds the world from the ground up, making every cobblestone, sign, building, awning, and apple by hand.

“When I read the story, it just felt like it has this textural, gritty quality—that quality you have in stop-motion of real light hitting real objects, things made of fabrics and wood,” says codirector Tony Stacchi. The production team mostly uses paper, wire, cloth, plastic, and a little fake fur to assemble the objects, and even designs its own fonts for all the signs to round out the world’s aesthetic.

The movie’s themes of bigotry and corruption also play into the production design, where the flowery ostentation is undergirded by a sense of decay. “Everything is twisted and torqued and stretched out,” says Travis Knight. “It’s almost as if the corruption of the town has burrowed its way into the cobblestones, into the marrow of the town, and twisted it.”

Practical Magic

Since they must construct every piece by hand, stop-motion animators were traditionally confined to limited sets and characters. Computer-generated imagery (CGI) blew those tiny worlds wide open.

Laika builds core elements individually—main characters, sets, props, even clouds—in order to maintain the handmade texture that gives stop-motion its feel. Then, using green screens, 50 computer artists expand upon these physical (“practical” in the lingo) objects, adding crowds, additional buildings, vast horizons, and special effects, with the aim of preserving the gritty feel instead of CGI’s glossy sheen.

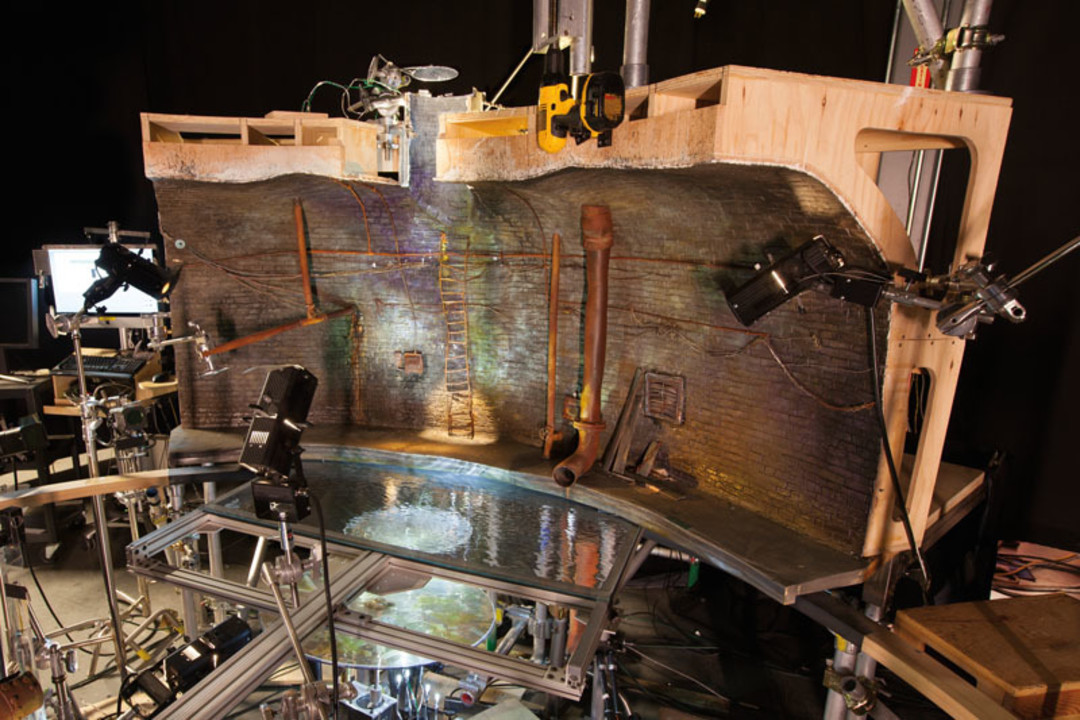

For instance, in this scene depicting Eggs in a sewer, computers could easily generate the water’s dancing reflection on the walls. Instead, a rigger devised a beautifully realistic practical effect by shining light through two rotating plates of rippled glass. CGI is used only to add moving shadows and dust glistening in the light.

“The layers of multiple extras, camera movement, and atmospheric work that we’re doing is far more complex than any past project,” says Steve Emerson, the visual effects supervisor. “By using technology, we’re doing things with this movie that typically aren’t seen in the genre.”