Author Mitchell S. Jackson Talks Portland, Prison, and Politics

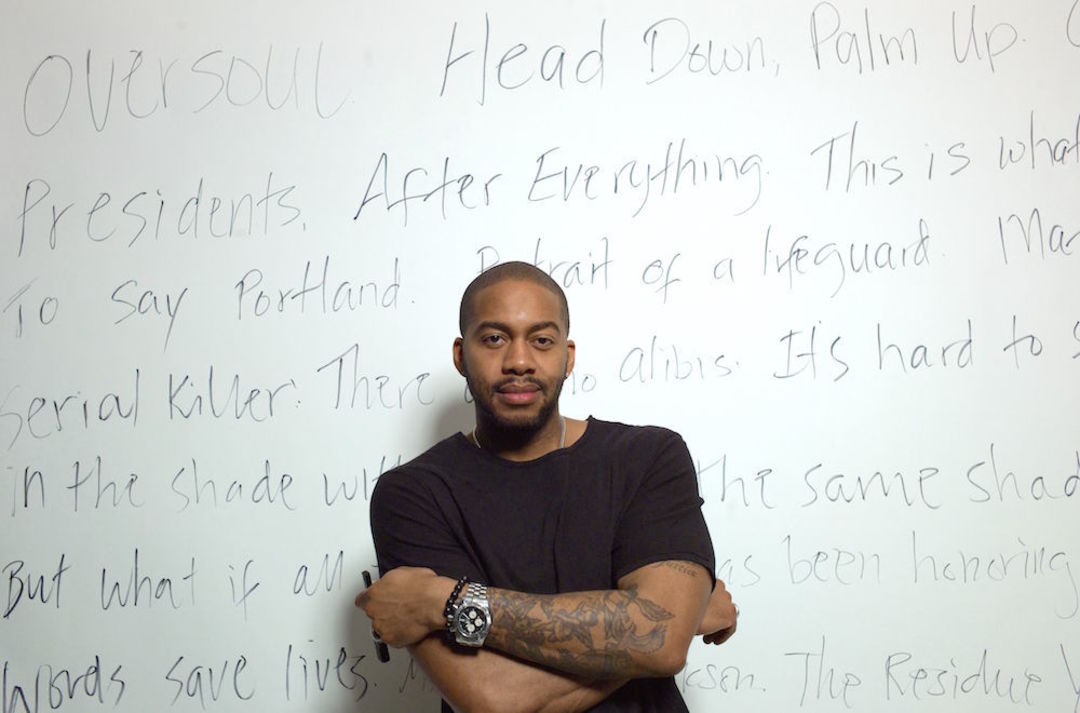

Image: Courtesy Mitchell S. Jackson

Portland-born Mitchell Jackson’s life doesn’t follow a typical trajectory: He’s gone from selling drugs off MLK to headlining at the Schnitz, with a 16-month stint in prison in between. His first novel, The Residue Years, was released in 2013, and hailed by the New York Times as a “powerful debut.” He now lives in Brooklyn, New York where he teaches writing at New York University, but was back in his hometown on March 10 for a reading at the Arlene Schnitzer concert hall. It's the culminating event for the 13th annual community reading project, Everybody Reads, for which Mitchell’s book was chosen this year. Before the event, we got Jackson on the phone to tell us about reading, writing, and returning home.

The Residue Years is autobiographical fiction, with two main characters: Champ, a smart young Portlander who sells drugs to make a buck, and his mother Grace, a crack addict raising three children in poverty. How much of the book is based on your own life?

It’s hard to say percentage wise, but what’s true is the basic premise. My mother struggled with addiction through my childhood and youth, and I’m the oldest of her children with two brothers, and I sold drugs for a little while and went to prison.

Was this a story that you felt compelled to write?

Yeah, absolutely. I felt that this kind of story about Portland hadn’t been told, or at least I wasn’t aware of it, and I really wanted to chronicle what was happening. For the city, but also for me, to chronicle what was happening in my family. And the more I wrote about it the more I was forced to reconcile it, or at least try to reconcile it. So it was therapeutic and also it gave me a sense of pride that I was able to keep the stories going–the stories of people that I’ve known from the city–that they would have some kind of legacy.

Much of the book is set in North and Northeast Portland in the nineties, where you grew up. Is that part of Portland recognizable to you any more, given the amount of change that has taken place in recent years?

It’s recognizable because those houses are still there. But it’s a significant change. The houses look the same but the businesses, the people in the neighborhoods are different. It also feels like it has a different kind of energy when I’m driving up NE 15th or down Fremont. I see people jogging on MLK with their dogs, and that just was not happening in the nineties. MLK was where all the prostitutes would work, and a block off MLK was where I sold my first piece of crack.

How does it make you feel to see it so transformed?

On the one hand it’s exciting, because I see people and they look genuinely happy to be in Northeast Portland. It’s always been a clean city, but now the buildings look refreshed and refurbished so that makes me feel heartened. But I also know that I’m not seeing the same people that I grew up with. It brings me down to know that the new happiness and prosperity that I’m seeing was at the cost of someone else’s home—not just their house, but the area they called home…[Gentrification] is very complicated. It does bring a certain kind of prosperity to a neighborhood, so you can’t just say it’s all bad. But on the other hand you have to think, what are the costs? What are the expenses from this change of people in an area? And if you’re the one getting displaced, I don’t think it’s all that great.

What was it like growing up in one of America’s whitest cities?

I didn’t really have that experience because Northeast Portland was black. We weren’t segregated, I didn’t know it was the whitest city in the country. Most of my friends were African American. I went to Jefferson High School which was African American … I’m not disagreeing with the statistics, but I didn’t live in that Portland.

Do you think it’s easier now for a young black man in America than it was when you grew up? Has the election of a black president helped?

I think it’s tougher. . . It’s harder to see the ways you are being oppressed, so it’s tough and harder to navigate. I remember [when Obama was elected] people were saying ‘Now you can really be anything you want to be’ but that just isn’t true. While it raised the pride of black males, I don’t think it really raised their expectations. It was a nice symbolic gesture – we probably won’t get another black man as a president. But good for him, he did a solid job.

There’s a moment when Champ talks to his college class after giving a speech, and one of those present tells him “Not everything is about race.” Champ’s reply? “That’s true, but maybe this is.” Would you describe The Residue Years as a book about race?

I think it’s a book about family at its heart, and I think it’s so closely rooted in my story and because I’m a black man, everything is about race, so it’s inescapable. And even if it isn’t about race, there’s that question in my head that always makes it about race.

How did you come to start selling drugs as a teenager?

I think the catalyst for it was that my mom was addicted, I was tired of being victimized, of seeing her leave and take the rent money, of not having enough for groceries, and of the lights being cut off. I decided I was going to make a way for myself for my brothers. It started as something that felt necessary, and then it morphed into something that was excessive.

As someone who’s been incarcerated for drugs, how do you feel about the prison system?

I think prison can work as a deterrent if the person is in the mental space to see it as such. You can go in there and say ‘I’m just going through this time’, or you can go in and say ‘I’m going to find ways to improve myself’, or you can just give up. Luckily I felt that I didn’t want to [sell drugs] any more, but I don’t think it was the prison that did it. I don’t think that many people are changing their paradigms in prison because of some program or conversation with a warden. You just figure out you don’t want that any more.

Was being in prison formative for you? What was its lasting effect?

Well, the first novel that I can remember reading I read in prison. It was by Terry McMillan—I think it was either Stella Got her Groove Back or Waiting to Exhale.

Now that you’ve written about that period of your life, do you find yourself short of material for your next work?

I don’t feel done with it. I think there are just so many stories connected to what happened in that era of my life that I haven’t explored, and I don’t have the imagination where I can write a Matrix or a science fiction book, so as long as these stories keep offering up what I think are some insights I owe it to myself to keep pursuing them…My mentor [literary editor Gordon Lish] says that you write from your wounds, that the thing that has hurt you the most that is also your greatest strength. And with my history, I’ve got enough [material] to last a lifetime.

How did it feel to be chosen for Everybody Reads?

It was really exciting because I wrote the book for Portland, it’s about Portland, I’m pro-Portland, so to me it was probably the most serious marker of progress. The other awards felt good but nothing feels like having people at home recognize your work.

What are your thoughts on the merits of Everybody Reads as a community reading project?

It’s so important, right? To get people reading, to give them incentive to read. And it creates a sense of community because the conversation is about one book. For someone like me, it’s given the book a wider audience. Without Everybody Reads, the reach of the book is so much smaller, so I’m really grateful that programs like this exist to make a book a conversation piece. . . This is one way to make books part of the popular conversation.

You’re now living in New York, in very different circumstances to the ones you left behind. Do you feel that Portland let you down? Do your experiences here—growing up poor, with an addict mother, ending up in prison—make you resent the city? Or do you still feel connected to Portland?

I absolutely feel connected to it. I don’t think it’s let me down—it’s made me. Whatever strengths I have, they were born in Portland. Even the obstacles—going to prison, having a mother that was addicted to drugs, making my way through a not-so-great Portland public school system—I wouldn’t trade them for anything. I’d be a different guy, then. Who knows? I might not be able to withstand these [East Coast] winters!

Mitchell S. Jackson will be at the Arlene Schnitzer Concert Hall on Tuesday, March 10 at 7:30 pm for Literary Arts’ Everybody Reads 2015: Mitchell S. Jackson event.