Is This Man Portland's Best Kept Jazz Secret?

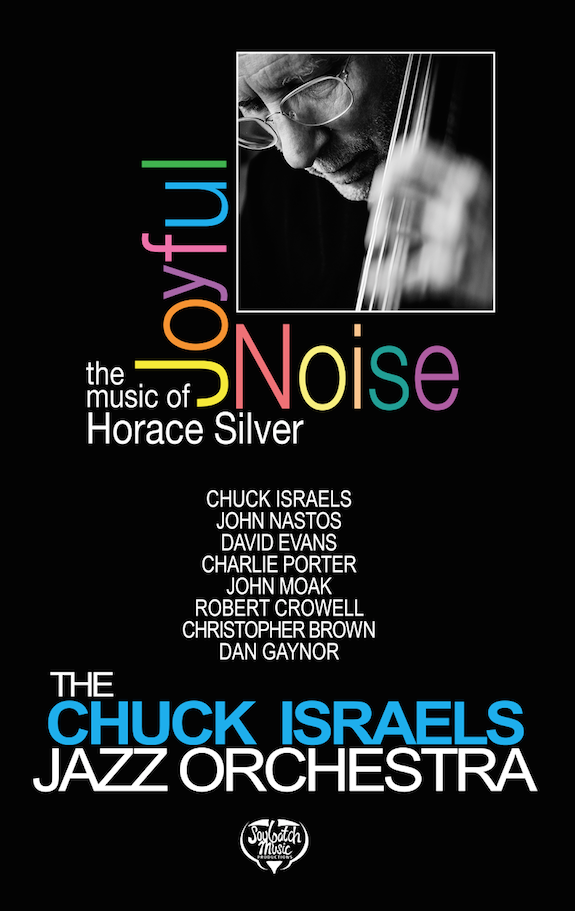

Chuck Israels. Photo credit: Charlie Porter

He’s played with Billie Holliday and recorded with John Coltrane. Lead Belly has eaten chocolate cake in his living room, which also played host to Pete Seeger. He was a long-time member of the Bill Evans Trio. And at 78, he's not done yet. We caught up with Portland's resident jazz legend Chuck Israels ahead of the release of his latest record, to talk about the nutritional value of music, and how he wants Portland to own the Chuck Israel Jazz Orchestra.

How did you find your way to jazz?

My stepfather was a very accomplished and fairly well known classical baritone. There were musicians of all kinds in our home, constantly. Classical musicians, folk musicians—I grew up with Pete Seeger and the Weavers in our house, and I remember Lead Belly being our living room and consuming an entire chocolate cake and a bottle of Muscatel in one afternoon.

So I had a strong classical music background and became interested in jazz at first when my parents put on a concert series in Cleveland where we were living at the time, and one show was with Louis Armstrong. I had dinner in between an afternoon and an evening performance with the guys in his band. At twelve years old that was pretty impressive!

You shared a stage with Billie Holiday—tell us how that came about.

It was in 1957, and my parents had a summer arts workshop for teenagers in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Seven miles away was the music barn which was a place that had concerts during the summer, and the people that ran that place knew me and they had hired Billie Holiday for a concert with her pianist, but they needed a bass player and drummer. They called me to back her up for that one concert.

I was 22 and pretty preoccupied with figuring out how to do a good job and there wasn’t much room in my consciousness to think about what she was doing and what she was like, I was just doing my job. It was one of the many of things that I was lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time for, when there was a lot of creative life in the jazz world and I had access to a lot of it from being in Boston and in New York. I was lucky. I grew up at a good time.

You went from Billie Holiday to recording with John Coltrane within a year—that seems more than lucky!

I had become friendly with a guy in Cambridge who had a record company—his name was Tom Wilson. I spent a lot of time helping him with his then fledgling record company and at one point he said ‘I’m going to make a record in New York in March (of 1958), will you play on it?’ And that’s how that happened. At that point John Coltrane was another of the good tenor saxophone players that was recently well known but he hadn’t yet become the icon that he is now. I was just feeling lucky that I was in the professional world of jazz musicians. We didn’t know John was going to be come the icon that he did.

Of all the big names in jazz that you’ve played with over the years, who was the biggest influence?

Bill Evans – that was the longest association I had, it was six years, and I played in [the Bill Evans Trio] with great joy and deep pleasure. I felt as if I had found my place. Bill’s musical aesthetics represented something that I didn’t even know I was looking for, but when I heard it, I thought immediately, ‘That’s what’s in the back of my mind!’

People still think of me as Bill Evans’s bass player, no matter what I do professionally beyond that—for better or for worse, I’m stuck with that. It is for better, until I want to go on from there and develop some other music and I get proposals to play Bill’s music with some other pianist, and sometimes they’re the most attractive financial offers that I get. But . . . it’s like being an Elvis impersonator—if you do it well you lose your own personality, but if you don’t do it well, then what’s the point? I don’t reject the aesthetic and the heritage of the legacy of things that I learned from Bill and shared with him, but he has been dead a few years, and it’s a little bit necrophiliac.

Who in the jazz world excites you today?

Boy, that’s a hard question. And the reason that’s a hard question is because the whole cultural picture has shifted so far from what I grew up in that the young musicians now are I think distracted from what I would hope to be their better musical ends by association with the popular music world around them, which has deteriorated terribly in the last fifty years.

Photo courtesy Chuck Israels

There’s always going to be something good hidden somewhere, but we have long ago left that golden age, that unusual period in which really sophisticated music written by educated people was part of popular culture, essentially the first half of the twentieth century. It was kind of parallel to Elizabethan theatre. For most of history, great art has not been popular art. It’s almost always been subsidized by governments or the church or monarchies. The first half of the twentieth century in this country was an unusual time when theater and films and music were really highly developed and being created by educated people for a very educated audience.

Here’s a simple way of looking at it: things were being sold to adults, not to children, because children didn’t have money. The advent of children having money didn’t happen until roughly 15 years after the end of World War II, and when children had money— and there were 76 million of them when the baby boom reached adolescence—the cultural picture changed.

What brought you to Portland?

After having a career in New York and after having lived in the Bay area for five years, I got a job in Bellingham, WA. And it was the first real financial stability that we had. The only drawback to that was the limitations to being in Bellingham, which is kind of a paradise of geographical and ecological location and a dessert of jazz culture. When we had enough money that I could retire from that teaching job, it was Seattle or Portland, and Portland looked more attractive to us, for all the reasons that everybody likes Portland. I also knew musicians here that I had some relationship with, and it was a fairly easy move.

We did have a sense that we could bring something here that might be needed and might be welcomed, and to a large extent we have found that, certainly among the community of msuicians, but to move that out into the general consciousness of people, and to help people to embrace this as belonging to them . . . That’s something about Pink Martini that I admire, is how they somehow have managed to belong to their community. And the community gives back by embracing them. That’s a great thing and I would love to have a portion of that. I would like Portland to own us a little bit the way they feel they own Pink Martini.

You put together the Chuck Israels Jazz Band here. How did that come together?

You come to town, you look for musicians, you hear them play, you make contact, you suggest other people, people play with you, and the ones that belong there stay and the ones that don’t find reasons not to be available.

What kind of audience did you find in Portland?

I don’t think the audience here is all that different from the audience in most places. There are a small group of people who are interested in having a real connection, a deep connection with music. And when we find those people, they love what we do. I really don’t know how to estimate what’s going on except that the people that are there when we play, you can feel their connection and their involvement with the music, it’s palpable. That’s a big part of my goal, to reach people on that level. And that doesn’t mean pandering to them.

I would like to find support for what I really believe has enduring value, and the things that have enduring value are in the immediate present more powerful. It’s a better meal – it’s better nutrition and it tastes better than fast food too. It’s the understanding of musical nutrition that has not caught up with the understanding of food nutrition. And it’s not as easy to demonstrate that there is such a thing as empty musical calories, and that they can fill up your consciousness and take the space that might otherwise be there for a more nourishing experience. The thing is that that more nourishing experience, it’s like food—it doesn’t have to taste bad just because it’s good for you.

The Chuck Israels Jazz Orchestra's Joyful Noise: The Music of Horace Silver is out this month. The band plays Jimmy Mak's on Friday, July 17.