The Dream of the 90s? A New Novel Set in Portland in 1992

Sara Jaffe. Photo by Nadia Cannon.

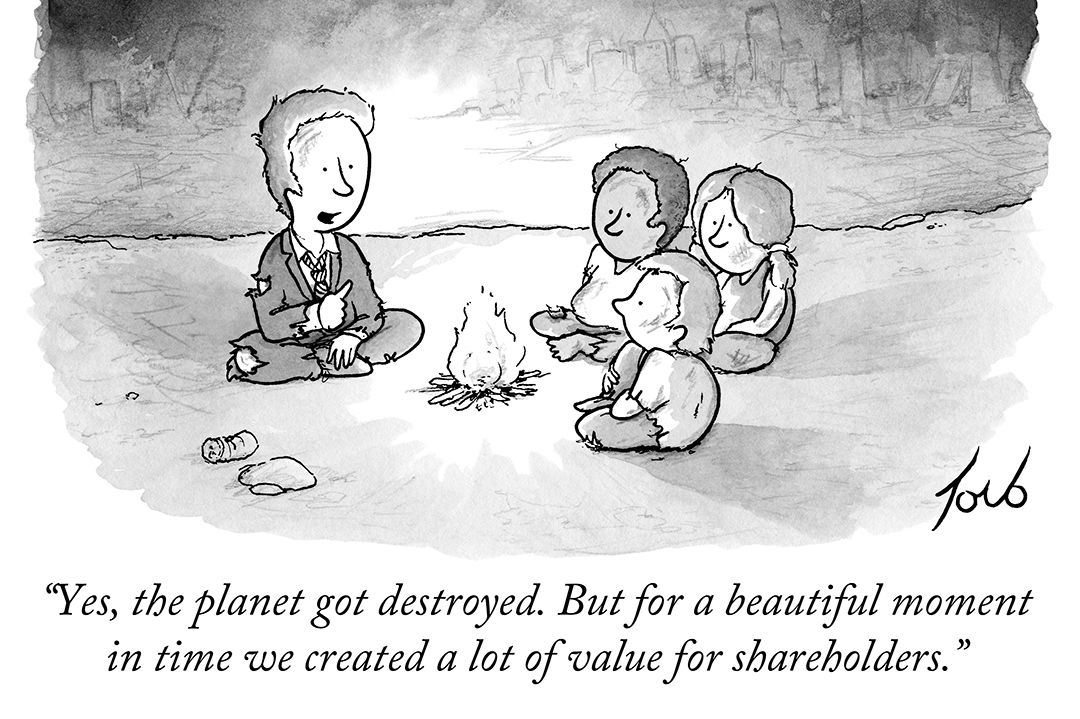

In 1992 in Portland, the Northeast was “kind of ghetto”, the weekend market was for buying Femo beads, and Rich’s “smelled like a million cigars”—at least for Julie Winter, the protagonist in Sara Jaffe’s new novel Dryland, which hits shelves next week. It's a coming of age tale about a high school student whose swimming champion brother has disappeared to Europe, and her initiation in high school swimming, as a way of reconnecting with him and of connecting with the team's popular swim captain, Alexis. We caught up with Jaffe ahead of her September 2 reading in Powell’s to talk about Portland as artistic material and artistic support.

Dryland was set in 1990s Portland. Was this city as a setting necessary to the story?

I didn’t want to set it in New Jersey [where I grew up], mostly because I wanted to create a distance form my own experience, but also because I felt there would be a little too much available to Julie if she lived just outside of New York city. From talking to my partner Nadia [a Portland native] and other people, there’s a sense that Portland then didn’t get stuff as quickly as New York city, and I wanted there to be that slight remove. Julie’s experience would have been different if she could have gotten on a bus and gotten to New York city—it would have been a different story.

And I think in terms of the mood and the tone, Portland made sense to me. I wanted it to be set in November, December, January. I wanted the constant gray. I’m really interested in a sort of flatness, both in terms of how I think about plot and how I think about mood. How can you make things feel really flat but still have stuff happening under the surface? It felt like the gray of Portland winter could capture that.

Though your portrait of Portland in 1992 is evocative and in detailed, you only moved here four years ago. How did you research the Portland of that time?

I lived here briefly in 1997 and ‘98—for seven months in ‘97 and then in the summer of ‘98, I took some time off undergrad and came out here. So I had some sense of it. And also my partner grew up here, so talking to her I got a sense of it.

I used some real Portland places and made up others, and it really didn’t seem interesting to me to have to have an allegiance to the geography of the city. That was not where I wanted to put my energy. So I use real street names but I don’t think about whether they’re exactly geographically accurate. I wanted to choose the details that felt necessary for Julie’s world and for telling a story, but I didn’t set out to have any kind of historical accuracy.

Were you worried about how people who did know 1990s Portland would take your version of the city?

I brought that up with my editor and she said, “It’s fine it doesn’t matter.” So I thought, “OK.” I wasn’t setting out to write a Portland novel, but maybe it did end up being more intrinsic to what I was writing than I realized…It did give me a nice container—once I figured it out I could limit the possibilities of what could happen in a way that I found useful.

The story is told through the first person, and feels deeply personal. How much of your own experience did you mine for the book and how much of it is a departure from that experience?

It’s pretty much entirely a departure from my own experience. I’m a lifelong mediocre swimmer—I love swimming but I’m not very good at it—but I didn’t grow up in Portland, I don’t have an older brother…Julie as a character is really different from me. I hadn’t thought about it this way before so I may be getting the terminology wrong, but I think there’s ways in which aspects of Julie are aspects of my id. She definitely behaves more badly, in terms of being bratty, than I ever really allowed myself to behave…I think that it lets me be more authentic on the page, to think about what are all ways, when you’re in the world, you hold yourself back for whatever reason. Would it be more authentic to put some of those more immediate ways of acting onto the page? Maybe this goes without saying, but fiction is a comment on reality, it’s not reality, so I don’t think people should act like that, but it’s useful for me to think about it in that way.

The book also pays tribute to some of the music of that era—REM’s “Country Feedback” gets some serious airplay. Was that something that you researched?

I did get weirdly fixated on making sure the dates of when music came out were right. I don’t know if you know this but you can look up the Wikipedia page for 1992, and see major things that happened in 1992, so I spent a bunch of time on that Wikipedia page. That was my research! But the music and fashion was really about my own recall of that time. I’m 38, so I’m the same age as Julia. That’s the most autobiographical aspect of it, in a way.

You’re also a musician, having played guitar in post-punk band Erase Errata for several years. Do music and writing cross-pollinate as artistic endeavors for you?

I have done some writing that really engages directly with being on tour or talks about different musicians that I’m interested in, and those kinds of things, more on a content level. But I think that also—and it may be pretentious to talk about it like this—but formally or structurally the way that I think about songs, whether they are songs I’m playing on guitar or songs I listen to, really resonates with how I think about structure and form in fiction. A friend of mine the other day told me that the pacing of the book Dryland reminded him of Gang of Four’s record Entertainment, which was the biggest compliment anyone could have given me! And it made sense to me. I like songs that are catchy but not necessarily conventional pop songs, that have a little noise thrown in, or have a structure that’s really repetitive. And I like plot but I don’t necessarily like a conventional plot arc, and I like realism but I want to also feel a little distance. That’s similar to how I feel about music

Sometimes if I’m trying to figure out what needs to happen in a scene, I’ll try to step back from it and hear it as if it were a song and think of what I would want, what tone needs to happen next. I don’t know if I can describe it more specifically than that, but if I can listen to it, it'll help me to know what note needs to be hit, or if it needs to pause.

You moved from New York to Portland four years ago. Has Portland facilitated your writing?

Yes. I think it has in part because it’s easier to stay home here, and that sounds like that’s saying something negative about the city, but it’s more that there’s a culture here of it being okay to stay home, in a way that in New York it’s totally not okay.

I came here with my writing community pretty firmly established in terms of the people that I share work with, who are my readers, the contemporaries I’m most invested in, but mostly they’re not here. But there are actually are a lot of people around here that I’ve connected with about writing in ways that aren’t so much about exchanging work but about talking about “What was your process of trying to get your book published?” or about helping set up readings, or more big picture stuff because there are so many people who are involved in creative endeavors here. So in a way my artistic community is not necessarily here, but I feel good about my writing work community here.

Your book has tapped into a wave of nostalgia for a Portland that is fast disappearing. Does it feel strange to have found yourself in that conversation, given how recently you arrived here?

Yeah, it does feel weird. But I think there’s nostalgia in that very rose -colored, apolitical form, and then there’s “Let’s look at how the city’s changed and how that’s affected people for better or for worse.” And it’s not like this is an overtly political book at all, but if anything I would want my contribution to be able to have those conversations too.

Sara Jaffe's novel Drylands is published by Tin House Books.

She launches the book with a reading at Powell's on September 2.