Writer John Irving on Religion, Reading, and Returning to Portland

John Irving

Since John Irving headlined the first ever Wordstock festival here in April, 2005, there have been a lot of changes—both to the city and its beloved literary festival. In the ten years since, while John Irving was knocking out four new novels, Wordstock soared, foundered, and then found a new home under the Literary Arts umbrella. Now Irving is coming back to a city he says he loves—and, he points out, has visited for other non-festival reasons in the intervening years—for the return of the festival that he helped launch.

It’s not the only recurrence we talk about in our lengthy phone call—Irving is generous with his time, and speaks in the kind of wordy, complete paragraphs that brook no interruption. His latest book, Avenue of Mysteries, revisits some familiar Irving preoccupations: circuses, missionaries, children with stand-in parents and extraordinary gifts, abortion, religion, a transvestite, and a writerly protagonist. And the writer makes no apologies.

“I always wished I could have asked Shakespeare ‘What is it with all the fools who are smarter than everybody else?’” he says to point up that he’s not the only writer who gets stuck on a trope. “’What is it with the witches? Who are these people? Because they’re always there.’”

In the case of Avenue of Mysteries, the old themes are given fresh life through the story of Juan Diego, a Mexican “dump kid” and autodidact, and his sister Lupe, who can read other people’s minds but cannot make herself understood by anybody other than her brother. Lupe, a feisty, opinionated heroine who is in many ways the book’s most compelling character, has a rare speech impediment and is convinced she can predict the future: sound familiar? It will to fans of Irving’s 1989 bestseller A Prayer for Owen Meany.

“When I start taking notes about Lupe, when I start sketching in details in a notebook long before I’m ready to write anything and I’m just thinking about her character, I’m a long time down that road before I realize ‘Oh God, it’s a little girl who’s Owen Meany all over again,’” says Irving, who adds that he is particularly preoccupied with characters who think they can predict the future, and the way this belief influences their actions. “I keep coming back to that subject, whether I want to or not.”

Unlike Owen Meany, Lupe grows up in Oaxaca, Mexico, where much of the novel takes place through the memories and dreams of an adult Juan Diego, now a successful writer on a trip to the Philippines.

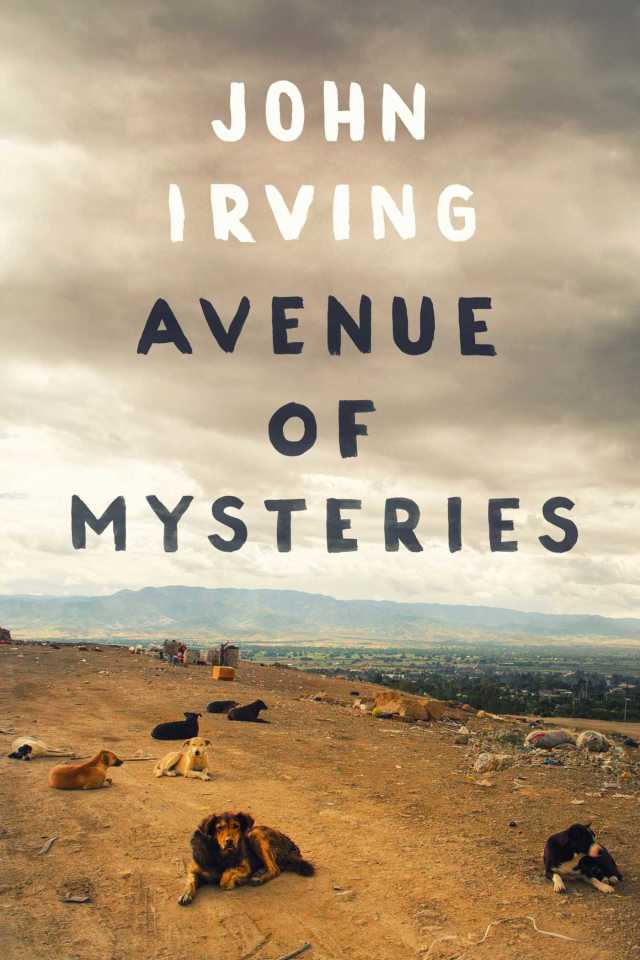

Avenue of Mysteries, by John Irving.

Specifically, Juan Diego is a highly successful, prolific writer who has written a novel about abortion and was once involved in the Iowa Writers Workshop. But John Irving will stop you right there. “I don’t see myself in most of the characters I write about,” he says with some frustration. He has, after all, been answering this same question over and over again, stretching back to his creation of a protagonist who was an Iowa graduate in 1972’s The Water-Method Man, or the novelist T.S. Garp in The World According to Garp. “I certainly use places I know about and experiences I’ve had in my fiction, but I don’t use them in the same way they happen to me,” says Irving. “I don’t think my own life or my own example is very interesting or is at all worth writing about.”

Yet there are real clues to the author’s inner life in the books he writes, numbering fourteen novels to date as well as several non-fiction works, screenplays, and a children’s book. “Perhaps the most autobiographical element in all my novels is that I do write about things that I’m afraid of,” he admits. “Rather than write about what happened to me, I write about situations I hope never happen to me, or to anyone I love.”

And as vivid as the characters he portrays may be—the sexually aggressive mother and daughter duo Miriam and Dorothy, the kindly missionary Eduardo Bonaparte, the atheist Dr Vargas, and the dogged, unquestioning Clark French all populate Avenue of Mysteries—they are fictional composites, rather than portraits of real people.

“There’s no former student of mine named Clark French who’s going to sue me, but there are several former students of mine who will recognize their eyebrows, or a remark here or there,” he says.

These characters, their passions, and the strange and novel details of their fictional existences are the force that drives Irving’s books, which still thrum with life as he continues to produce them at a clip through his eighth decade.

But Irving also uses them as vehicles to examine and articulate his own social and political preoccupations, and he returns again in Avenue of Mysteries to some of his particular peeves, among them organized religion.

Juan Diego and his sister, who spend part of the novel in an orphanage run by priests, weigh in regularly on the Catholic Church, with Lupe particularly and often hilariously unimpressed by the Virgin Mary. Yet Irving gives them, alongside their anti-church sentiment, a belief in magic—an eagerness to seek out miracles.

“Yes, there are some serious questions or put downs of the social and political policies of the Catholic Church [in the book],” he says. “Duh, what else is new? But I’m not putting down what people believe in. I’m saying ‘There’s gotta be something to these miraculous virgins—they’ve lasted a long time!’ You might dispute how they’ve been used, how they’ve been manipulated over time, but you can’t dispute the power of belief or the power to heal.”

In fact, Irving describes himself as a “kind of average, run-of-the-mill agnostic” and has as little time for atheism as he does for the Catholic Church. “I think it’s vain and presumptuous to presume that what you believe, everyone else should also believe, and that would include atheism among the so-called true beliefs. In other words, people who are so convinced of their religions that they proselytize it to others, I find very tiresome.”

That impatience in conversation—you can tell Irving doesn’t suffer fools—is given gentler expression in his work. Avenue of Mysteries’ Dr Vargas, one such atheist who refuses to let go of his strict adherence to scientific fact, even in the face of things that can’t be explained, may be uncompromising, but he’s not unsympathetic. And one of the novel’s most endearing characters, Eduardo Bonshaw, is a missionary whose very job description involves the kind of proselytizing that Irving decries.

He speaks of these men, and of the novel's myriad other vivid characters, with affection and care, even as he moves towards the next project. Avenue of Mysteries is Irving’s fourteenth novel, but he’s clearly not stopping there. He’s got so many more books in him, in fact, that he’s had to stop reading.

“I used to read everything. I became a writer because I loved to read, and I fortunately read things that made me wish I’d written them, principally those novels of the 19th century that made me want to be a novelist,” he says. “But I don’t read much any more and I especially don’t read much that’s new any more.”

He offers a pretty convincing excuse, however. “One reason I don’t have time to read is that I’m writing all the time,” he says, and puts it in a way that, at least for Irving fans, brooks little argument. “Do I want to write or do I want to read? And the answer is I’d rather write. Because I have more things I want to write than I’m probably going to get to.”

He’s 73, and brimming with ideas by the sounds of things, enumerating three or four new novels that are in his head, not to mention a teleplay, and “a couple of screenplays” that he’s working on. Plus there’s the Wordstock appearance coming up. As Irving puts it: “I’ve got lots to do.”

John Irving will be speaking at Wordstock on November 7.