Monica Drake on the Folly of Loving Portland

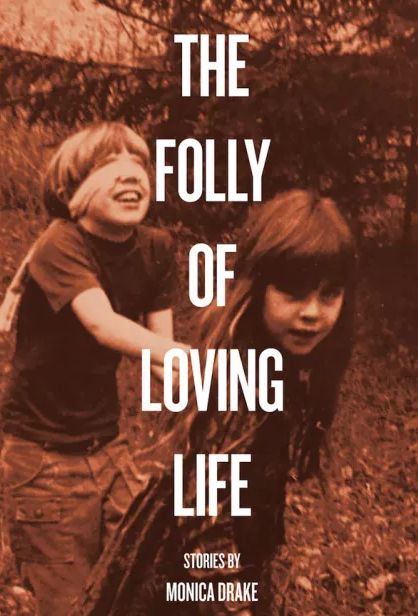

Image: Bellen Drake

Monica Drake, longtime Portland resident and member of that writer’s group—yeah, the one with Chuck Palahniuk, Lidia Yuknavitch, and Chelsea Cain, with Cheryl Strayed among its erstwhile members—has a new short story collection, The Folly of Loving Life, out on March 8 (Future Tense Books). It follows her debut novel, Clown Girl—lauded by Entertainment Weekly for its “emotional through-line”—and her second, The Stud Book, which Publishers’ Weekly praised for its depiction of Portland.

Her new emotionally attuned and haunting collection spans decades in a changing Portland, seen through the eyes of different members of a family nursing its own emotional wounds. We caught up with Drake ahead of her February 29 reading at Powell’s to hear about having Chuck Palahniuk recite your work in Powell’s, and why Portland’s writing community still rocks.

You’ve had two successful, acclaimed novels. What led to your move to short stories?

These were written over 15, 20 years—at least, some of them. Some of them are very, very new. There are some pieces in there that go back to when I first started writing really. Kevin [Sampsell, of Future Tense Books] had come to me asking for a short story collection, and I started pulling stories out. I wouldn't have done it without his encouragement.

These stories each work alone, but combine to form a portrait of a family over decades, intersecting with repeated characters at different moments. Was that always the intention?

Originally it was just going to be a short story collection, where none of the stories have any accountability to the next story in the collection. But when I started looking at it, there was a kind of world-building quality, and I started looking at which stories of mine spoke to the next story and considering the characters. Then I started writing new work, and just enjoying that feeling of building the world. So that’s when it moved from a story collection to a really integrated story collection.

Were you always a short story writer at heart, then?

I did start by writing short stories—I didn’t write a novel until I finished graduate school. When I first started writing, I was interested in all of those writers that were kind of a big deal back then, including Ethan Canin. I loved his work, I loved Alice Munro, I loved Raymond Carver—all of those realistic American writers who could navigate a line between working class and an intellectual element. I was kind of talking back to that stream of voices when I was writing.

Do you have a specific reader in mind when you write?

The readers in my mind are the people who contact me with great frequency on social media—some of them I haven’t met, but they’re out there and I appreciate those readers. My other readers are my workshop group, which is very specifically Chuck Palahniuk, Lydia Yuknavitch, Chelsea Cain, Suzy Vitello, and some other people. It’s a very specific group of people who have enjoyed sharing work for years, and that creates a very specific audience.

That’s a pretty high-profile group of writers. How much do you think being part of that community has informed your work?

I took a class from Tom Spanbauer, and Chuck Palahniuk was in that class. I was writing these short, kind of cuckoo stories, and I was down at Powell’s one time and heard someone talking loudly. I realized they were reciting lines from these little immature stories I’d been generating, and it was Chuck. He was calling out to me by remembering sentences that I wrote. It was so funny and flattering and interesting, and I think it was gestures like that that made writing really fun. Those kind of things built the community and kept me personally writing, and in some ways it is just an extended conversation with those writers that I love. I’m just lucky to have the writers I love right in the room.

Did being around other writers like them help to legitimize the activity?

Back then none of us had really published anything, so maybe we didn’t notice if we were taking it seriously. Tom Spanbauer took it seriously, and he was amazing. I think he generated a lot of stamina for us all.

You were in his Dangerous Writing workshop?

I was his first student in that here in town, and he’s kept going from then, so it’s been a long time. It was really Tom’s workshop that got me so excited about writing.

Image: Future Tense Books

You and Palahniuk, Vitello, and others branched out to form your own group. Do you still meet?

We do. Cheryl Strayed was in there for a while. She’s moved on for now, theoretically she could come back if she wanted—she can hang out with Oprah, or she can come back with us…

How does it help to get together with other writers regularly?

Writing’s really hard, and I am not fast at it, so you have to be in it for the long haul. And if you’re going to be in it for the long haul, it has to be enjoyable. I’ve been doing this for 25 years now, and so how are you going to get through 25 years when you’re going to have a lot of rejection? When you’ve got really cool people you can talk to and share your work with and maybe get them to recite your lines once in a blue moon, that’s big feedback. Plus you get to see their work and see it grow and evolve. That’s just a dream. That’s the only way to do it, I think. There are some writers that just like to write in isolation, but I don’t know—you just gotta keep it fun somehow. People think of that word "fun" as trivial, but it’s really so crucial.

Your work has always been very rooted in Portland. How important is sense of place to your writing?

This collection is Portland—from downtown out toward the foot of Mount Hood is the sprawl. And Clown Girl was located in a fictional town called Baloneytown, but everyone has seen through that as my rendition of Portland. The Stud Book is all set in Portland—it’s the story of seven different characters woven over what it means to be an adult in this city. With this one it is looking at a 20-year span of life in Portland. And there are things that change. In the beginning they’re living on a couple of acres and in the end they’re living in pretty cramped back yard sheds, so I think that’s sort of what’s happened in Portland. That sense of space is largely diminished.

How do you feel about those changes to the city you weave into your stories, changes that have become a hot-button topic?

In Clown Girl, the main character lives on almost no income, and when I tried to sell that to New York, people in the publishing industry in New York could not see it. The comments indicated that they had a hard time imagining someone living on so little money. And the thing is, it was a fictionalized version of my own experience, and I lived for a long time here on very little money, so little money. Some of that was based on compromises. It wasn’t having a glamorous life on little money—it was that people in Portland didn’t care about that stuff. When I was a young person in this city, I had very, very cheap places to live with a lot of compromises and I didn’t mind any of that because it left time and space to think about politics and ideas and theories, and just live your life. I think Portlandia came in and made fun of a lot of the outcome of rethinking ways to live, with their famous “What kind of life did this chicken?” have question. But that’s just mocking the superficial manifestation of what’s actually rooted in a really conscious approach to rethinking living.

How do you think the city’s artistic output will be affected by the rise in cost of living and property prices?

When I was younger, the thing that allowed me to write short stories was not some big dream of making it rich or selling my work to Hollywood, it was wanting to communicate and build something interesting with words on the page. I had my typewriter on a Goodwill desk in a walk-in closet and that was my office, and I had an apartment that barely cost $100. That was all I needed. But I feel like this town has ratcheted up where you can’t find that cheap living space and you don’t get your own walk-in closet any more. Unless you have enough money.

It doesn't seem to have affected the city's literary output, though. There are still so many books coming out of this town.

I feel like everybody’s writing—and everybody should be writing! Portland is just lucky and thick with it. I think Portland has an amazing writing community too—writing isn’t just the written work that we make, it’s the whole approach as a value system and a lifestyle, and I love the way the different networks of writers have gotten closer together in Portland. There are different kitchen table classes and reading series and they’ve started to blur and have more outreach to each other. It’s interesting and supportive.

It’s easy for writers to be jealous of each other’s accomplishments or be embittered or feel rejection and failure. But in the Portland writing community as it stands, there’s a great acceptance of everyone being at their own place, and an awareness about supporting each other where we stand.

Monica Drake reads at Powell's City of Books at 7:30 pm on Monday, Feb 29.