From a Sexy Jewel Thief to a Sexy Ghost, Imago Theatre Mines Japanese Pulp

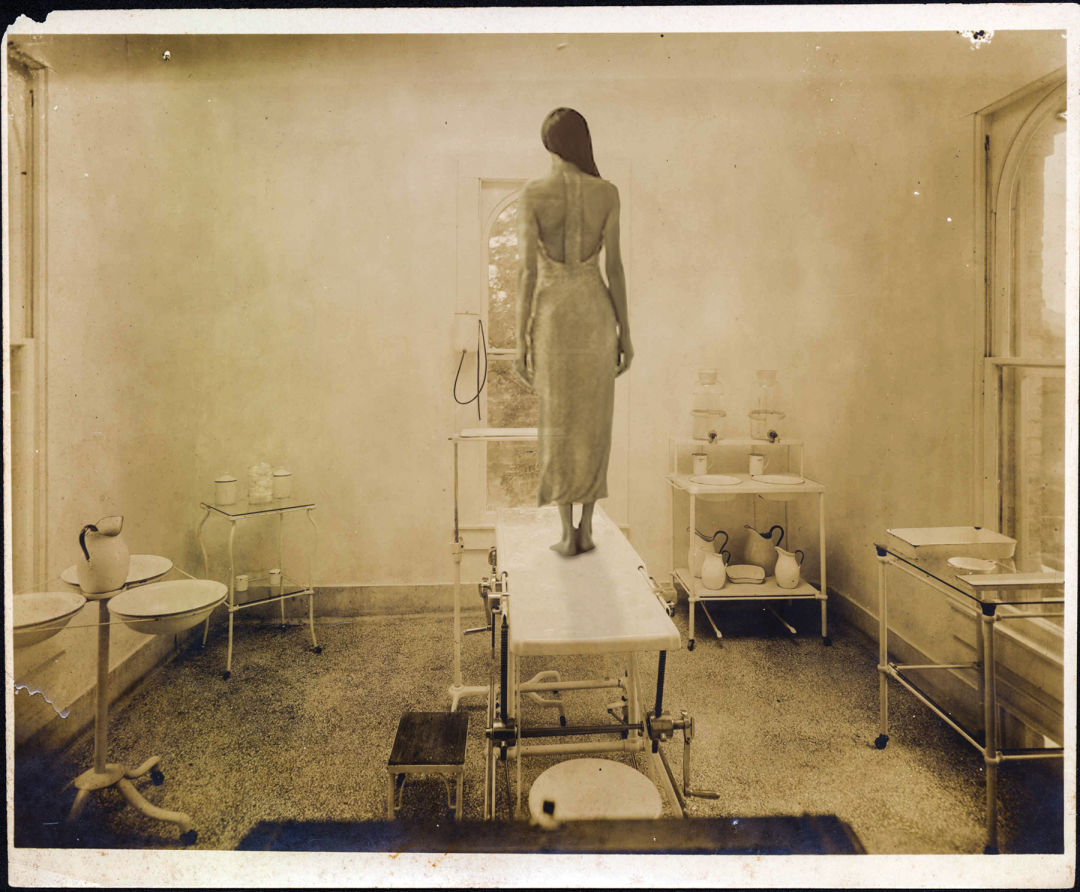

Image: David Deide

Four years ago, Imago Theatre scored a hit with a noirish tale of a sexy jewel thief. That was The Black Lizard by Yukio Mishima, a Nobel Prize-nominated Japanese writer probably better known in the US for his ritual suicide—he committed seppuku, a ceremonial disembowelment historically associated with samurai—than for his riffs on classical Noh drama.

In The Lady Aoi, Imago’s second crack at Mishima, it’s all about a sexy—and sex-crazed—ghost. (With a bonus appearance by an alluring nurse.)

“There’s definitely a pulpy, cheesy quality to it,” says Imago co-artistic director Jerry Mouawad, who also directed The Black Lizard. “I don’t know if Mishima intended to go there, but I’m going there with it.”

Where Mouawad is going is to a hospital in 1956. As this cryptic, pulpy ghost story begins, a man has come to visit his ailing wife. But it’s never quite clear what the woman’s maladies are, or what sort of medicine she’s receiving—just oblique talk of “sexual complexes.” And as soon as the nurse departs (sorry, folks!), a ghost arrives: stylish, wildly jealous, and hell-bent on getting back her man and doing away with this other meddling woman. Unlike our Caspers or Moaning Myrtles, this is a living ghost of Japanese lore: the spirit of someone still alive and kicking, not someone six feet under.

Jeannie Rogers (left) is a living ghost. Gwendolyn Duffy is maybe asleep.

“What if every time you went to bed, you were so troubled by something that you manifested a ghost that came to life?” Mouawad says. “While our Western stories come from some kind of superficial supernatural, this comes from a real human emotion.”

For Mouawad, the show offers him another chance to dip into what he calls “chamber theater”—occasionally miking the actors, as he did in The Black Lizard. But it’s not for amplification. “It’s to find other things in there,” Mouawad says. “Why put on a mic if you’re not exploring what your voice and emotions can do when you’re talking at lower, hushed levels? It gives you the opportunity to go more interior.”

Mouawad has also patched together ambient sound loops by composers John Berendzen and Greg Ives, some of which were created 20 years ago. The result is a moody, haunting soundscape—often spacey and portentous, with the occasional scratchy synth bit or jazzy burst of keys. There’s a live percussionist onstage, too, punctuating dialogue with a hit of the drum or a clang of the cymbals.

It’s a brief show, only about 50 minutes. But at a recent rehearsal, Mouawad admits he’s still puzzling through it. Which isn’t surprising, given the story’s lengthy history: Mishima wrote the play in 1954, but it’s based on a 15th-century Noh drama, which itself draws from an 11th-century novel. And some of the questions posed in the play seem just as old. Namely: can sex ever be separated from emotion? The nurse has a monologue suggesting this is the hospital’s charge—to separate the physical act of sex from all those messy human feelings.

“I think this is an examination Mishima went through,” Mouawad says. “He was an openly gay man in the ‘40s and ‘50s in Japan, and according to Larry [Kominz, a professor of Japanese at Portland State], he had a pretty active nightlife and a pretty opposite professional day life. So he’s playing with all these polarities—sexuality and emotional complexity, and what happens at night and what happens in the day. I’m still unraveling it all.”

The Lady Aoi runs March 11-27 at Imago Theatre.