Two Portland Artists Weigh In on Beyoncé’s Lemonade

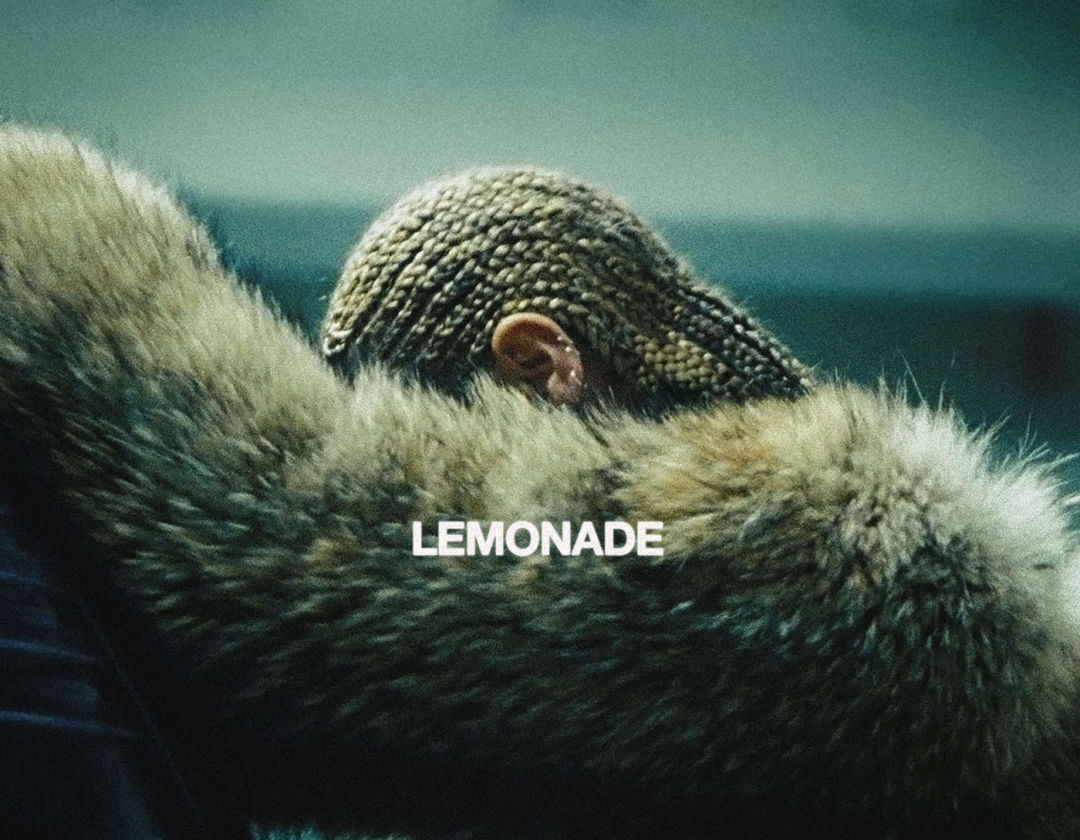

Beyoncé's Lemonade

Beyoncé’s Lemonade has been blowing minds and blowing up news feeds since its surprise release three weeks ago. Ahead of a Portland screening and panel discussion on its cultural impact, we asked two local artists for their take.

First impressions

Melissa Lowery, director of Black Girl in Suburbia: My first impressions were, "Wow!" It felt so raw, but in a way that was validating for me and liberating. For me, the whole theme running through it was this generational aspect of love and strength and anger and heartbreak and power and struggle, all of these things that have been passed down from generation to generation. It felt very specific in who she was targeting and what she was trying to share, which is these generational patterns that we black women have passed down to our daughters, sometimes not even realizing or knowing it. Patterns of dealing with men, black men, relationships we have with each other.

Intisar Abioto, photographer and creator of The Black Portlanders: I had not seen something produced of that caliber, particular form, and length devoted to black women in this generation. I think it’s because Beyoncé has such capital, and can get so many people on board to produce something like this. I think because of the power she has, I thought it was amazing. I was moved.

The visuals

Lowery: I think the visual aspect makes it real and it allows you to connect more with the music and with what she’s saying and where she’s coming from, then it sparks all of your senses, your brain is triggered and you’re firing away, you’re emotionally invested. When that happens, it’s a home run.

Abioto: It was such a cascade of images from different places and people, different aesthetics and feelings, and if I’m honest I wouldn’t say that the images that were in the piece are images I’ve never seen. I live with black women, I come from black women, and I come from traditions of thinking about our history and past and future, so for me what I saw wasn’t something particularly new, but things that I know and live personally. But they are images I don’t see put out frequently in that particular way.

As someone who is an image maker, someone who is really focused on people in the African diaspora and bringing those stories, our ideas, our faces and our dreams to the front of the consciousness of people of African descent but also to the world, I would say that I am appreciative of her, because sometimes you don’t want to be one of the few who’s doing that. You need to be a recipient of the art experience, too. We need it too.

The politics

Abioto: If you’re talking about black women, our ideas, our bodies, our dreams, are politicized—even our being in a place—is politicized, I would say policed. It shouldn’t be that big a deal for women, human beings, to talk about their ideas, to speak about who they are, to be themselves without asking permission from any person or being. If it is an issue, why is it an issue to have a piece that is just about black women?

Lowery: I say it was liberating because I myself have in the last year been working on how to create space for my voice because I’ve been so used to and so conditioned not to tell my truth when I need to tell my truth. It’s always about making people comfortable, and when people get uncomfortable I back down from what it is I need to share. Particularly white people—I don’t want to say too much for fear of making you uncomfortable or making you upset.

I think Beyoncé has been really great at sharing that aspect of women and black women, and when you create a space to share your voice, not to apologize for it, to say I am entitled to say what it is I have to say. She puts it out there: “I’m not sorry, I’m not going to apologize if you’re uncomfortable, I’m not going to apologize if you don’t understand it—this is my truth, this is my voice.”

Abioto: The work was definitely about black women. I also think art pushes a culture, art pushes people, and she put this work out there, and you can’t stop people from engaging about it and talking about it and like learning from the art itself. But I think there are limits. She is showcasing aspects of black women's collective knowledge in a visual arts format. It is complex. Beyoncé may own Lemonade, but even she doesn't own the collective experiences of black women. She refers to it in her piece. Who has ownership of that knowledge? Black women do, collectively. Who can speak on it from a place of authority? Black women.

I see it as okay for someone who may not be a black woman or may not be a black person to critique the aesthetic, or the production. Where I see the limit is you can’t critique the experience, you can’t tell black women what our stories are, or presume to speak about it from a place of authority. It's a clarification of the "for." It is not "for you" in that way. It may be "for you" to experience or engage with as an arts piece, but there are limits. I think it’s a real balance.

The takeaway

Lowery: Beyoncé is standing up and saying to women—and to black women specifically—“Stand in your truth and don’t apologize for it. Be who you are and get done what you need to get done.” So she definitely is an inspiration for myself and for my daughters. My oldest daughter, who is 14, watched it and straight after said, “I am so empowered as a black woman.”

I’m grateful to Beyoncé for putting this video out and for the voice that she has been over this last year. Say what you will about her, but she’s got a ton of black girls inspired and ready to go conquer the world.

Nothing Real Can Be Threatened: A Screening and Panel on Lemonade takes place on Tuesday, May 24 at the Whitsell Auditorium. Intisar Abioto and Melissa Lowery will be joined on the panel by Hanifah Abioto, Rukaiyah Adams, Deena Bee, Jenna Marie Fletcher, Jamondria Harris, Margaret Jacobsen, and Cicely Rodgers. Sold out.