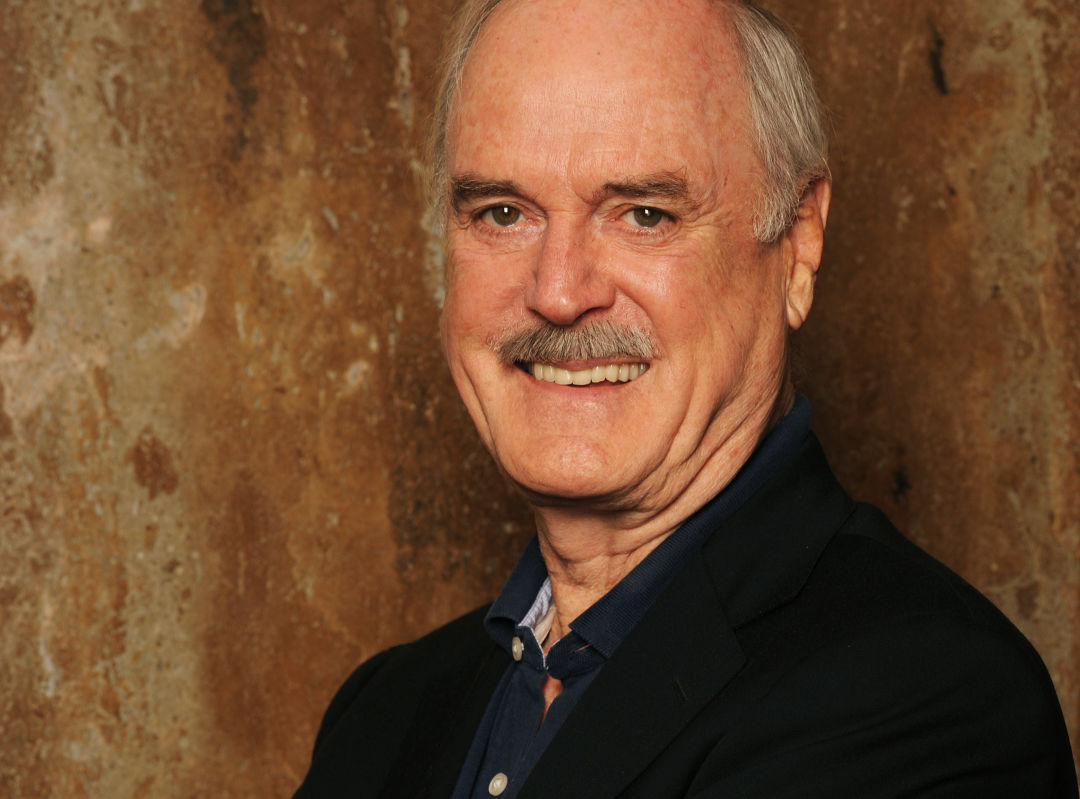

John Cleese Wants Your Crankiest Questions

Image: Courtesy Oregon Symphony

For a good chunk of my childhood, Saturday evenings meant Monty Python. Off in a far room of the house, various parental units played high-stakes Scrabble, free to curse and swill cheap red wine. They laughed—a lot. But I don’t know if these evenings left them utterly gut-busted from hours of rib-clutching, tear-streaming, spastic guffawing. For me, Monty Python set the bar early, and high, for how funny funny could get.

John Cleese was at the center of that experience, from the Ministry of Silly Walks to the Argument Clinic. For others, peak Cleese may be Basil Fawlty of Fawlty Towers, Deadly Dirk in the Life of Brian, the Black Knight in Monty Python at the Holy Grail, or, of course, the randy barrister in A Fish Called Wanda.

Cleese, now 77, hasn’t slowed down. Last spring, he and fellow Monty Python alum Eric Idle toured the US and Canada. Now he’s back, this time solo, for a string of back-to-back comedy events. He hits Portland on Wednesday, March 15. What should audiences expect? In his words, “if they like Monty Python, if they like The Holy Grail, if they like A Fish Called Wanda, they will enjoy the evening. If they don’t like it, I will personally give them their money back after the show."

We caught up with Cleese in advance of the show.

The format for your Portland show is part monologue, part multimedia. What can audiences expect?

I’ve got quite a nice 60-minute presentation: a little bit about my childhood, and when I discovered I could be funny, and how I got in show business by accident, and then bits from shows like Python (just quick bits there, because people know it very well), maybe something from Fawlty Towers, maybe something from Holy Grail, maybe something from Life of Brian. Something from a Fish Called Wanda. You see what I mean? After 42 minutes, people begin to doze off, so I like to have one or two clips from programs I’ve done, and photographs. And after that we have Q&A. Questions are the bit that I always look forward to, because they’re unpredictable.

But you've probably already been asked just about everything!

[Chuckles.] Audiences ask me terrible, terrible questions. Like, "Why can’t you stay married?" The worst question I got was in Florida: "Why did the Queen kill Diana?" Somebody asked Eric Idle once what his favorite sexual position was, and I thought, how is he going to get out of that one? And he said, "It’s the male marital position: man flat on his back with his wallet wide open." So you never know what you’re going to get.

You've been to Portland before. That kind of question might be a bit off-brand for us.

Portland is like anywhere where the weather tends not to be terribly good; people read a lot of books, they tend to be a bit more thoughtful and, to be brutal, a bit more intelligent. But it’s nice if the questions are a bit aggressive. Like, "Why don’t you pull yourself together?" Or, "Why did you think that was funny?" That's much nicer than people who get up, as they do in California, and say "Oh, Mr. Cleese, I love your stuff so much, when I was a child I used to watch you with my grandmother, and then she died four years ago." Yes, but it’s not very interesting to the audience. If they ask you a technical question—"Why did you put that particular scene in there?" Or, '"I always thought that was a bit tasteless—did you?" Those kind of questions get really interesting. I don’t get offended if somebody asks me a critical question. People like to hear what’s going on on the inside.

You've been entertaining people for nearly 60 years. Doesn't the pressure get a bit much?

When I was young, I did feel at times that when I went to dinner people were sitting there waiting for me to be funny. And of course I refused; I just wanted to be myself. And my natural self depends on the people sitting at the table, the atmosphere. But when I go out onstage now, I am comforted by the fact that very few people bought tickets who don’t like what I do. I get a nice reception when I come out, people are very warm, because when someone makes you laugh you feel affection, no question—no matter how awful you are. I used to say of W. C. Fields: wonderfully awful man, really coarse, and everybody loved him because he was so funny. It’s a bit the same with Basil Fawlty.

You're on the record as being quite political in the UK. Do your interests extend to the United States?

I’ve followed American politics for a very long time, because my first visit here to the States was in 1964. So I was here for the Lyndon Johnson-Barry Goldwater election. I’ve followed your politics quite closely ever since. And I do find the current development quite extraordinary. Just the idea that people could make statements, and when asked to justify them, they say things like, "well, I’m sure there must be something in it," or, "a lot of people have told me that."

Extraordinary—do you think unprecedented?

I have to say it’s not much better in the United Kingdom. It used to be. But during the reign of Thatcher, the problem was that she no longer sought to justify what she said. She would just say something and we were all expected to say, "oh, I see that’s the case." And that was in the '80s. I think our standard of debate has gone downhill ever since. But I don’t think we’ve quite reached the point that you did a few days ago, when President Trump claimed that Obama had wiretapped him. The FBI indicates that that didn’t happen, Clapper indicates that it didn’t happen, and the President lets everyone know that he doesn’t believe them. If you’ve got a President who doesn’t believe his own secret services, I don’t know what you’ve got left.

Any advice for us?

Perhaps the thing to say is that none of it matters because we’re all dead in the long run. It’s a good way of looking at it. This too shall pass. It’s frightening, but also terribly entertaining.

Our arts editor, who is Irish, wants me to ask you about Brexit.

Oh yes! Well, there were a lot of people who were in favor of Brexit that I don’t like at all, like Rupert Murdoch. But I was persuaded when I read certain people—not the immigration obsessives, I read people like David Owen who’d been our foreign secretary in the Wilson government, and James Dyson, the inventor, and Christopher Booker, who is, I think, one of the best writers in England. And I came to the conclusion that the United Kingdom didn’t work nearly as well as the Americans seem to assume it did.