Take Unpublished Poems by August Wilson. Add Musical Theater. What Happens?

The poet’s terrors personified, in UniSon at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

In 2014, three artists met in a dining room in Seattle’s Capitol Hill neighborhood. Four manila folders sat on the table and bankers boxes were stacked on a nearby bench, all filled with typewritten pages, hand scrawlings, and scraps of paper—the unpublished poetry of legendary playwright August Wilson, who lived in that house from 1994 till his death in 2005.

“It wasn’t filtered,” says Steven Sapp, one of the trio at the table, part of the New York–based performance collective Universes. Few besides Wilson and his widow, Constanza Romero, had ever handled the papers. “It was written on a typewriter, it was handwritten, it was him doodling on the side of a page, it was on napkins, it was on the back of menus from a diner where he hung out in Pittsburgh.”

After two days combing through the collection, flagging poems that moved them, Universes—whose work fuses theater, music, movement, and spoken word—pitched Romero: could they develop a show inspired by this unpublished work? Romero, who had seen the group perform and later been introduced through a mutual friend, said yes.

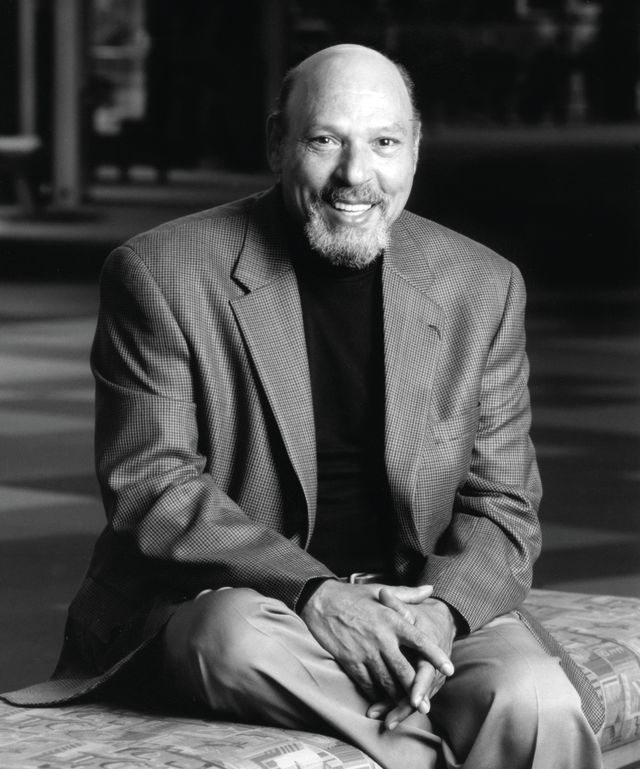

Universes members Steven Sapp, Mildred Ruiz-Sapp, and William Ruiz

The result is UniSon, a musical premiering this month at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland. It’s tempting to shorthand the show as “the August Wilson musical.” And, yes, there’s no doubt Wilson, who won two Pulitzers for his 10-play cycle chronicling black life in Pittsburgh’s working-class Hill District, will draw audiences. But the show’s creators are firm: this is not an August Wilson poetry slam. Rather, audiences can expect energetic choreography; songs drawn from the blues, Spanish bolero, hip-hop, and jazz; and a script that, while containing excerpts of Wilson’s verse, is an original work itself.

“The poems were like a treasure map,” says Universes’ Mildred Ruiz-Sapp, Steven’s wife. (William Ruiz, her brother, rounds out the trio behind this show.) Their challenge was to make it their own. “We’re a little bit removed from the August Wilson rulebook. We create musical theater.”

In their research, Universes came across a Wilson poem about a box filled with secrets, given as a gift. In UniSon, a dying poet leaves such a box to his apprentice, which turns out to contain seven “terrors”—a reference to another Wilson poem.

“Everybody has things in their life they hope to put away before they die, so we started to craft a story around what kind of legacies we as poets and as artists leave behind,” Ruiz-Sapp says. “What do we leave for those who look up to us? What do they find that we may not want them to? What are the skeletons in the closet?”

In a way, these unpublished poems are Wilson’s skeletons. “There’s poetry about animals, there’s poetry about death, there’s bloody poetry, there’s sexual poetry, there’s poetry about his family, about his mother and father,” says UniSon director Robert O’Hara, who helmed last season’s lush production of The Wiz at OSF.

Much more than that, those involved in UniSon are unwilling to divulge. It’s a seductive cliffhanger for Wilson fans—anyone who’s seen or read one of his plays knows his poetic command of language, that rare harmony between the lyrical and the vernacular. And poetry is how Wilson got his start as a writer in Pittsburgh: according to his New York Times obit, he proclaimed himself a poet at age 20. He continued to write poetry throughout his life, and in a 1999 Paris Review interview called the medium “the highest form of literature.”

August Wilson

UniSon, then, gives us a glimpse of some little-seen work, and could help introduce new audiences to this titan of American theater. “We’re coming from a different generation,” Ruiz-Sapp says, “so we wanted to lift it out of August’s timeline and bring it a generation forward.”

The show could also find audiences beyond Oregon. Universes’ first work for OSF, 2012’s Party People, played the Public Theater in New York City last fall. Several other OSF commissions—including All the Way and The Great Society, Robert Schenkkan’s two-part drama about LBJ, and Lynn Nottage’s Sweat—have also met national success in recent years.

Romero, Wilson’s widow, saw Party People on its original run with her then-teenage daughter, Azula. She recounted the experience to Universes that weekend in Seattle, Sapp says. As the two exited the theater, Azula turned to her mother: “Why couldn’t Daddy’s work be more like that?”

Count the next generation in.