Portland Artist Arvie Smith Paints the Black Experience in Blazing Color

Aunt Jemima greets you from the center of the painting, her face locked in a deferential half smile, a butter-capped stack of pancakes in each hand. A child clings to her back, his copper-soled feet peeking out beneath her full bosom. The sky swirls in blue and pink, a spotlight spits its yellow glare, and a Confederate flag flutters above an American one. A leering Klansman leads a young black woman away from the police tape and off the canvas. An arrow points to a chalk body outline. Houses burn. A whirring movie camera captures it all.

Arvie Smith painted Hands Up Don’t Shoot in the wake of the 2014 police killing of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri. But that incident, obviously, isn’t the only element at play on this busy canvas. Smith connects Brown’s death to a long history of racist imagery used by the advertising industry, to media coverage of black people, to centuries of bigotry. And he does this all with fantastic beauty—lush color and fluid brushwork—and a sardonic, rakish touch.

Hands Up Don't Shoot, a 2015 oil painting

Image: Courtesy Arvie Smith

This tension—confrontation versus seduction, violence rendered with vibrancy—marks the Portland artist’s decades-long career. Smith is easily one of the city’s most technically skilled painters, and as he nears 80 his artistic vision seems as sharp as ever. In his paintings, buxom women swivel their hips, grinning kids chomp slices of watermelon in unsubtle parodies of stereotype, blackface performers gallop through minstrel shows, and interracial couples lock in lusty embrace. But Klansmen lurk in the corners, and slave ships hover on the horizon.

Smith’s themes are permanently, tragically relevant, and it goes without saying that his work packs particular charge in our acrid moment. He collapses history, erasing the divide between past and present. From Smith’s perspective, pleasure and pain are never far apart.

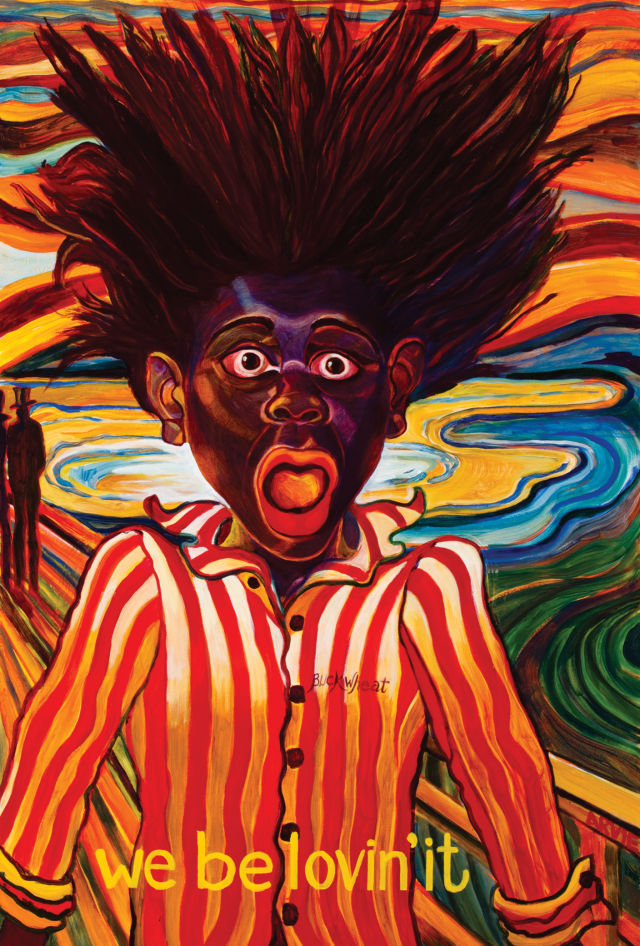

In his grimmest painting, Strange Fruit, several Klansmen lynch a naked black man. It’s towering in its depiction of violence (at nearly eight feet tall, literally towering). The scene is brutal, but Smith—who was raised in the Jim Crow South—renders the Klansmen’s robes with a near-baroque sensibility, creating ripples and wrinkles of fabric with countless layers of paint. In person, the image seems to glow. In another color-blasted work, Smith places a shock-eyed, shock-haired Buckwheat in Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Below Buckwheat’s cartoonishly horror-struck face, text reads, “we be lovin’ it,” a reference to McDonald’s ads that depicted black people as double Dutch–jumping, R&B-singing McNugget gluttons.

“There’s always this element of risk in his pieces,” says Bonnie Laing-Malcolmson, who curated an exhibit of Smith’s work at the Portland Art Museum last year. “It’s the inherent risk of being an African American man. How are people going to take you? You’re not just a person. You’re an African American man, and it’s a threatening position. It’s a threatened position.”

Laing-Malcolmson goes on: “But, for me, it also comes down to the fact that he’s just a beautiful painter. He can really, really paint.”

In person, Arvie Smith has none of the provocative, confrontational force of his paintings. He’s a big guy—six-foot-five at his peak, though he’s shrunk an inch or two with age—with a warm voice and a gray mustache. Mellow, unassuming, and quick to laugh, he often wears black sneakers and a tasseled mudcloth cap from one of his many trips to Mali. He’s as likely to explain what inspired a scene—a Shirley Temple movie, Baltimore’s famous Pimlico horse track, Hurricane Katrina, his mother—as to point out the compositional principles and color theory behind it.

Above all, however, he emphasizes identity. “I started off wanting to be an artist,” Smith says. “But now, I demand to be a black artist.” That demand drives Smith’s unapologetic portrayals of slave auctions and lynchings, but also helps explain his cheeky embrace of racist caricatures. “Flip the joke, slip the yoke,” he says, riffing on the title of a Ralph Ellison essay.

We Be Lovin’ It, from 2009, references both Edvard Munch and McDonald’s advertising.

Image: Courtesy Arvie Smith

Smith was born in 1938 in Houston, and at age 3 moved east to Jasper, Texas, which he describes as a cowboy town where lynchings were commonplace. (Jasper made national news in 1998, when three white men chained a black man, James Byrd, to a pickup truck and dragged him until he was dead.) Smith spent his early childhood with his grandparents, Hattie and George Washington Page, both educators. His great-grandmother, Harriet Finley, born into slavery, lived with them, too. Smith recalls the “crazy quilts” she used to stitch, and how she tasked him with weeding her herb garden.

They lived on a farm outside of Jasper, a sizable chunk of land Smith says made them “the rich black folks on the hill”—on the white side of town. “My understanding is that my great-grandmother married a plantation owner’s son, and that’s where the land came from,” Smith says. “But I have no idea, really.”

Smith says he, along with older sister Iris and younger brother Charles, often played next door in the shell of a farmhouse burnt out years before by the KKK. In town, blacks were supposed to step off the sidewalk when whites passed, but Smith’s grandfather—a history professor at an all-black college who always wore a suit and tie to work—instructed his grandkids to hold their ground. He also forbade them from the movie theater, not wanting them to be shunted to the balcony—“nigger heaven,” some called it.

“You always felt the tension—the terror, sometimes,” Smith says.

Smith’s grandfather gave him a book about Michelangelo, which he dutifully copied. But at his “separate but equal” school—run by his grandmother—a white teacher named Ms. Brenner had some sage words for Smith as he helped her wash paintbrushes.

“She told me, ‘Arvie, draw the people outside the window,’” he says.

What Smith saw outside the window in Jasper were signs reading “coloreds only.” He saw his grandfather’s watermelons, smashed by white kids. He saw horses, including his own, a bay named Ball he’d sometimes ride to school. (“I don’t know who named him,” Smith says, laughing.) Ball was the subject of a copper tooling Smith made as a boy. “I got a lot of accolades for that,” he says. “I remember thinking it was something I could get used to.”

At 13, Smith and his siblings left Texas to join their mother, Eola, in Los Angeles, where she worked as a hairdresser. (Their father, Connie, owned a dry cleaning business in Houston.) South Central LA in the ’50s was a jarring adjustment from rural Texas, and Smith fell in with gangs. “It was just sort of a must,” he says. “There’s no father figure, so your buddies are your family.” He kept up his art in high school, though, making posters before big football games. After graduating, he walked into LA’s Otis College of Art and Design.

“The receptionist looked at me and said, ‘We don’t need your kind,’” Smith says. “I didn’t know I needed a portfolio. Ghetto schools don’t really prepare you for that.”

For the next 20-some years, Smith bounced around. After two failed marriages and four kids (“You send ’em a check ... I see them occasionally but I’m not really in their lives at all,” he says), he split from LA and spent some time in Haight-Ashbury in San Francisco. He moved to a commune in the Idaho panhandle, and then to another commune outside of Vancouver, British Columbia, where he earned money, along with all the free beer he wanted, doing pastel portraits at a local pub. In the late ’70s, with his Canadian dollars running low and his legal status questionable, he flipped a coin between Seattle and Portland—California was unthinkable—and made his way to Oregon, where he landed a counselor job at what’s now Oregon Health & Science University.

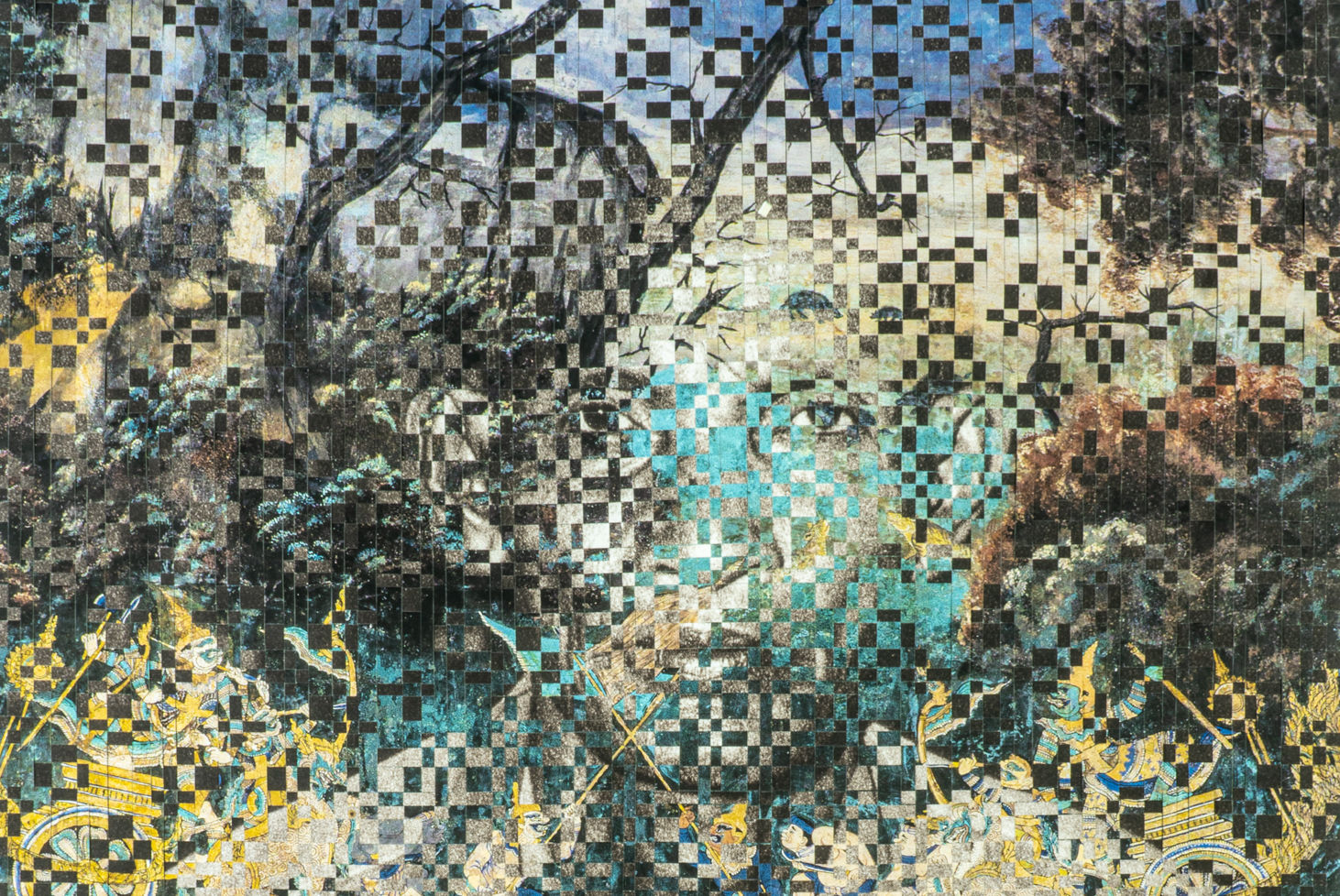

Trapeze Artist, from 2014

Image: Courtesy Arvie Smith

A few years later, while working at a boys’ residential treatment center, he made an impression on his boss. “He was gorgeous,” says Julie Kern Smith. “He used to have a huge afro, and it had a gray stripe through it. He was with this group of kids, teaching them to draw, and they just loved him. He was like the Pied Piper—kids were always around him.”

The two started dating, married in 1986, and now live in the Piedmont neighborhood, in a century-old home filled with West African masks and sculptures. Julie eventually persuaded Smith to quit his job and pursue art full-time. At age 42, he enrolled at the Pacific Northwest College of Art. “I didn’t want to be dismissed as a self-taught artist,” Smith says. “I had some heroes—Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt, those Flemish guys—and I wanted to know how they did that. I wanted the recognition. I wanted to be accepted as an artist. This goes way back. My mother had bought this Sears painting—you know, with some mountains—and we had one of my paintings next to it. Her boyfriend says, ‘Oh, it’s so nice to see amateur work next to professional work.’ And my thought was, ‘I’ll show you.’”

At PNCA, Smith stood out. “His work was always very strong and very specific to him and the fact that he’s black,” says painter Lucinda Parker, who was teaching at PNCA at the time. “It was a very white school then. Going to this art school as a black man, and later in life, that took moxie.”

Laing-Malcolmson also met Smith at PNCA. “I’ll always remember him sitting in front of me with this portfolio of mostly watercolors that were beautifully, fluidly painted, with African American figures,” she says. “He always had his own direction.”

At PNCA and in graduate school at the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore—he worked as a graduate assistant for famed abstract expressionist Grace Hartigan—Smith refined skills he’d developed painting murals on the walls of various apartments along the way, often to the horror of his landlords. “You have to reach for it,” Hartigan told Smith, urging him to push his subject matter and to take on larger canvases. Smith met landmark black painter (and one-time Portlander) Robert Colescott, whose work loudly and luridly satirized racial and sexual stereotypes.

“I said, ‘Whoa—this is what I always wanted to do but didn’t think was OK,’” Smith says of Colescott. “He would say it’s OK to talk about these things that you’re not responsible for. Someone identifies me as a ‘coon,’ and somewhere along the line, you identify with that. Those are things I try to flip on their heads.”

Smith learned to use color to upend expectations, too. “He paints people from yellow to purple black,” says Berrisford Boothe, an artist and professor at Pennsylvania’s Lehigh University, who met Smith in the ’80s. “We’re colored people. Literally. I’ve never seen an artist who’s more truthfully made us colored.”

The monumental Strange Fruit: oil on an 8-foot-tall canvas

Image: Courtesy Arvie Smith

In 1992, while still in grad school, Smith painted Strange Fruit, his almost-eight-foot-tall image of a lynching. It was bleaker than most of his previous work, sparked by reports he’d heard about cross burnings outside of Baltimore. Julie sewed Klan robes for a pair of models, so Smith could observe how the fabric fell. “I came in, and they were all suited up. It was wild,” Smith says. “And then I noticed one guy was wearing tennis shoes and jeans. And I was like—that’s it.”

He transferred that detail to the final canvas, an eerily humanizing, modernizing touch that makes the scene impossible to dismiss as history. A Klansman’s bloodshot eyes bore out from the painting’s center. An American flag flutters in the corner. It’s horrific, and yet Smith brings florid beauty to the canvas.

“I was working with movement and these swirls of the costumed figure,” he says. “You’re attracted by the movement and the beauty of the color, and then you actually see what’s going on.”

Smith would continue to apply that beauty-meets-horror tack to his work, though often with much more humor. In 2014’s Bojangles Ascending the Stairs, Smith reimagines the 1935 film The Little Colonel with Shirley Temple all grown up, breasts popping out of her dress, suavely dipped by Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. The painting satirizes art history, inverting Marcel Duchamp’s famous nude, and of course dramatizes white supremacist fantasies/nightmares. But, more specifically, it reappropriates the dynamic of the film itself, which portrayed Robinson as a dim-witted, childlike figure opposite America’s precocious sweetheart.

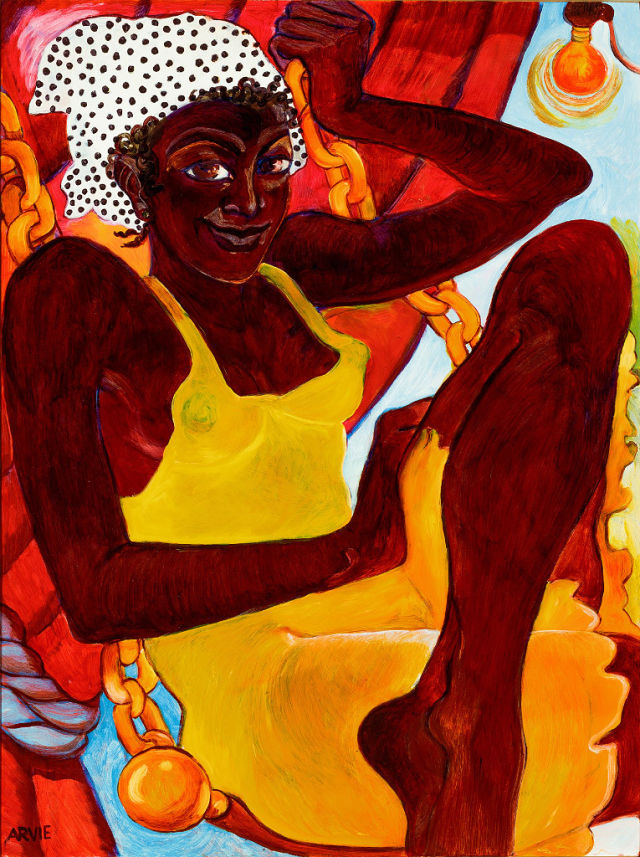

Arvie Smith’s 2014 oil-on-linen painting Bojangles Ascending the Stairs simultaneously satirizes both Marcel Duchamp and a Shirley Temple film.

Image: Courtesy Arvie Smith

It’s daring, but also sexy. You don’t have to spend much time studying his work to suss out what might be Smith’s favorite subject: women. “How do I put this?” he says, standing before a gorgeous 2002 painting called Luciana Dancing with Angels, a canvas drenched in yellows and pinks and oranges. “I think the female body is the most beautiful thing in the world.”

Parker describes Smith’s best work as “saucy.”

“I think he gets a lot of pleasure out of painting,” she says. “His work has always had a lot to do with flamboyancy, costume, humor, visual action. It’s a sardonic, humorous mixture of criticism and celebration. It’s not easy to paint like that in this white town of ours.”

Major recognition has eluded Smith. He hasn’t been represented by a Portland gallery since 2009, nor has he attracted much national attention. He’s made some high-profile sales: news anchor Charlayne Hunter-Gault gave Nelson Mandela one of his paintings, an image of a boxer in Everlast shorts, and another painting sold at auction to Dan and Priscilla Wieden. Smith’s recent exhibit at the Portland Art Museum marked a major solo showcase; PAM bought Strange Fruit, and the Hallie Ford Museum in Salem has promised him a show in the future. (According to PAM press manager Ian Gillingham, museum guards—often artists themselves—adored Smith’s show, and would point lost-looking visitors to his paintings.)

“I never felt any kind of pressure that my work had to support me,” says Smith, who enjoyed financial security as a PNCA professor. “I don’t paint to match people’s couches or drapes. Change your drapes.” (One couple did redesign a room around a Smith painting.)

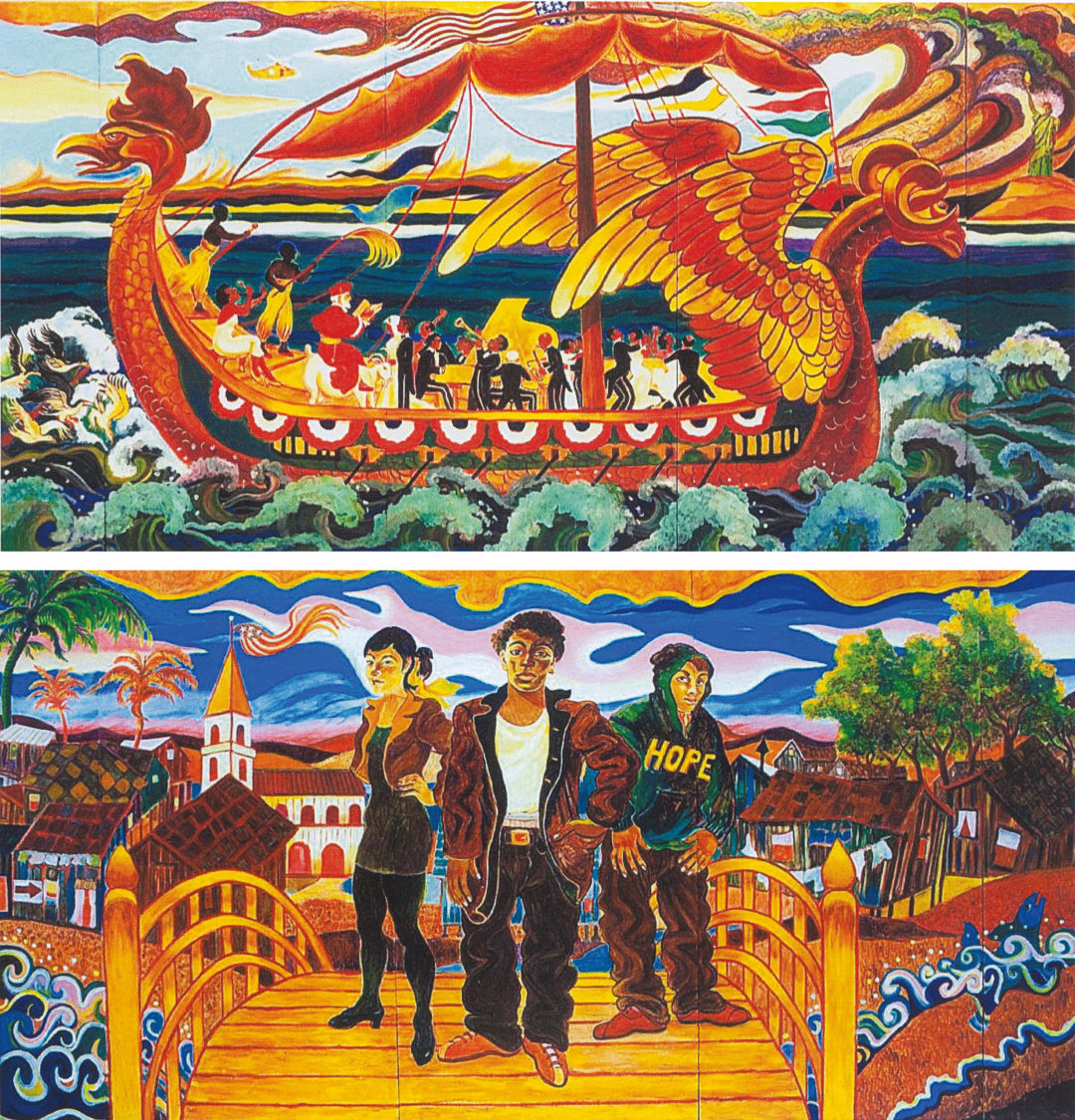

Two murals from a collaboration between Smith and youth at the Donald E. Long Juvenile Center: My ship has sales that are made of silk and I Am Somebody

Image: Courtesy Arvie Smith

Smith has thrown himself into community work, including youth projects at Self Enhancement Inc and a two-year mural project with young offenders at Multnomah County’s Donald E. Long Juvenile Detention Center. He was recently commissioned to create an 18-by-24-foot mural for Alberta Commons, a new retail center at the corner of NE Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard and Alberta Street projected for completion this fall. Drawing together the Vanport Flood, the construction of Memorial Coliseum, and real estate segregation, it’s a portrait of displacement and resilience among the neighborhood’s black population. At the center, a man holds a child who points to a flag reading “Still I Rise”—a reference to a poem by Maya Angelou.

Anyone who knows Smith’s work will recognize the mural as his. For most who pass by, however, it will serve as an introduction to an exceptional, idiosyncratic artist. His paintings may not have reached the halls of the Met or gone up for auction at Sotheby’s, but Smith’s body of work—including this huge, public expression of his complicated feelings about being black in his adopted city—is gutsy, gorgeous, and urgent.

Now retired from PNCA, Smith spends most of his time painting in his home studio. “I don’t have a lot of friends,” he says. “I don’t have a lot of people who come by and visit me. To put it bluntly, if I’m gonna get some paintings done, now is not the time to—.” He pauses. “I don’t have forever.”

Top Image: Arvie Smith in his studio (Courtesy Intisar Abioto)