How Aminé Became Portland Hip-Hop's Most Elusive Star

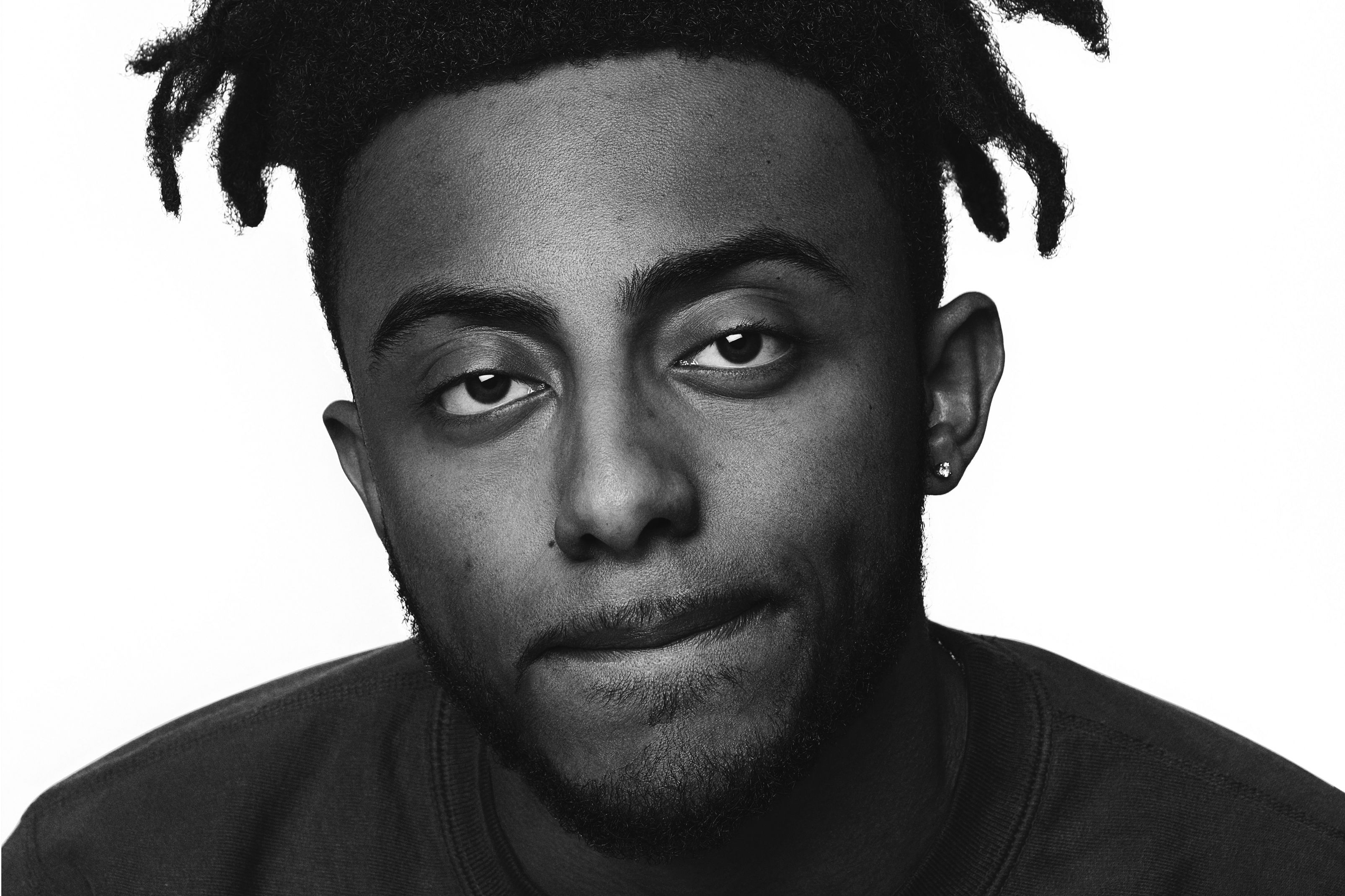

A skinny, gap-toothed kid gesticulates wildly in the parking lot of Mike’s Drive-In in Oregon City. Short dreads stick up on either side of his head, like antennae to some alien planet. His friends, in the deep background, hang out of a silver Honda, goofing on one another. But it’s nearly impossible to take your eyes off the skinny kid, with his awkward dance moves and urgent facial expressions. He commands your attention. He needs it.

This is the video for Aminé’s persistently catchy “Caroline,” a half-sung, half-rapped summer anthem that went viral in 2016—the video has more than 200 million YouTube views, and the kid front and center is the artist himself. It’s Aminé’s best-known song, and for most music fans both within his home city of Portland and beyond, it represented the MC/singer/director’s colorful first impression.

Aminé—born Adam Amine Daniel, son of Ethiopian and Eritrean immigrants to Portland and a graduate of Benson High—had been around awhile before “Caroline” hit. His debut album, Odyssey to Me, appeared in 2014, though it has long been expunged from the commercial internet. It begins with a low-key prophecy: “I’m headed to my next show / I gotta go / Headed to that Madison Square / 25,000 fans in the air.” Then an accented female voice repeats “Adam, wake up.” It’s Aminé’s mother, coaxing him back to Portland obscurity. But it’s too late. The dream has taken root.

Aminé hasn’t played Madison Square Garden just yet, but he has definitely found a bigger stage. In 2017, the hip-hop magazine XXL included him in its influential Freshman Class, which functions as a sort of critical watchlist of stars in the making. Billboard and the New York Times both weighed in favorably, the latter calling his major-label debut, Good for You, “one of this year’s most intriguing hip-hop albums and also a bold statement of left-field pop.” The album sold 13,000 copies in its first week, debuting at no. 34 on Billboard’s US charts. After a set at Lollapalooza, Daniel posed for photographs with his arm around a new fan, Malia Obama.

Through sheer will and a catchy song, a colorful dream world became Aminé’s reality. From the outside, it’s like he came out of nowhere. That’s intentional. To become the next big thing in the music world of the late 2010s, you have to let the world in on the ground floor. That can sometimes mean recalibrating, or even erasing, your pre-fame history. All the way along, Aminé—who, through manager Justin Lehmann, declined to be interviewed for this piece and did not respond to requests for comment on this story—had boosters and collaborators. Some have come along for the ride. Some were left in the dust. This is the years-long story of Aminé’s overnight success.

Born in 1994, Aminé grew up in Northeast Portland. He’s said his biggest aspiration back then was “to be Kobe Bryant,” a dream dashed when he was cut from the Benson basketball team as a freshman. But he also grew up in a musical environment—he’s told interviewers his parents listened to everything from Ethiopian music to John Mayer—and music eventually became an obsession. In his first recorded performance, he told Vice in August, he rapped about girls and rival high schools over Waka Flocka Flame’s “O Let’s Do It.”

Josh Hickman, a thoughtful and soft-spoken 26-year-old, is three years Aminé’s senior. He also went to Benson and both ran track, but the two barely knew each other then. Three years after high school graduation, as Hickman began his senior year at Portland State University, he connected with Daniel, a PSU freshman, who messaged him about music.

“My first impression of Adam was that he seemed older than he was,” says Hickman, who spent his college years composing and producing rap music under the name Jahosh. “There was a determination, or a focus, that resonated with me. It probably goes back to track and field at Benson. We would work out six days a week. It really instilled me with this work ethic and discipline. So when I met Adam, I was just like, ‘Man this is dope. He’s just like me.’”

Daniel loaned Hickman money to buy a microphone and portable vocal booth, and they began writing and recording on a relentless schedule. “He would come over in the morning and he wouldn’t leave till night,” Hickman says. “But it didn’t even feel like work.” Daniel would give Hickman input on the beats; Hickman says he helped with song concepts and even lyrics. Together they created the first DIY Aminé release, a mixtape called Genuine Thoughts.

With help from PSU music students whom the charismatic Daniel had recruited along the way—including multi-instrumentalist Irvin Mejia, who would go on to produce “Caroline” and other songs on Aminé’s major-label debut—Hickman went on to produce the bulk of Odyssey to Me in his windowless recording studio in East Portland in late 2013. The album’s songs run from vulnerable, confessional slow-burners (“My Emotions”) to explicit sex jams (“Feelin’ Like”). It’s ambitious both sonically and conceptually: The cover art adapts the poster from Richard Ayoade’s 2010 cult film Submarine, about a small-town 15-year-old named Oliver looking to lose his virginity. The album echoes the film’s plot in places, and references its protagonist throughout.

By Odyssey to Me’s 2014 release, Aminé had picked up a few key supporters in Portland, including Fahiym Acuay, an MC and writer (under the name Mac Smiff) for the popular regional hip-hop blog We Out Here. Meeting Aminé for a video interview, Acuay remembers a funny, slightly shy kid who seemed unusually driven. “He knew that he was a little bit different,” Acuay says. “He had a really different sound—kind of playful—but he also had these really deep melodies.” Acuay became an evangelist for the young artist: “I was screaming to the moon, ‘Check out Aminé! He’s doing the thing! Are you guys paying attention?’”

While local acts like U-Krew, Five Fingers of Funk, Lifesavas, and Cool Nutz have made some waves, Portland has never spawned a true national hip-hop star. Instead, we have a closed rap ecosystem with its own set of references, stylistic tendencies, and small-town kingpins. Portland rap artists tend to be judged more on their lyricism and verbal ability than on their melodic instincts or pop savvy. And on those fronts, Acuay notes, Aminé is no match for local mainstays like Illmaculate and Rasheed Jamal—battle-tested MCs with dense, intricate rhyme delivery. In fact, if Aminé had emerged a decade earlier, there’s a good chance he’d figure in the Portland hip-hop story as an eccentric side character, selling mixtapes out of his trunk at rap shows. But Aminé was born in a new era, where the home-burned CD has been replaced by lightly curated “mixtape” download websites that connect artists directly to a national audience, with no middleman and no local-cred hurdles to clear.

And Daniel knew how to work that system. He spent $1,000 of his student loan money to secure Odyssey to Me a spot in the featured albums section of Datpiff.com, a popular hip-hop mixtape-sharing blog that has served as a bellwether for artists like Drake and Chance the Rapper. By the end of summer 2014, Odyssey had reached 20,000 downloads. Daniel and Hickman found a promoter to take a punt on them—Ibeth Hernandez, who offered them a show at Peter’s Room in the Roseland, opening for critically acclaimed California hip-hop trio Pac Div. “It was so sweet,” Hernandez remembers of Daniel and Hickman. “They got me a thank-you card afterward, and it had, like, a Starbucks gift card inside.”

But the biggest payoffs came from shows Aminé and Jahosh booked for themselves. A few days after Christmas 2013, they threw a show marking Odyssey’s imminent release, hit social media hard, and drew 250. A party the next year drew 400, among them Blazers star Damian Lillard. His presence alone hinted that Daniel and Hickman had sidestepped most Portland hip-hop rites of passage. Not everybody would be happy about it.

But Daniel was making connections outside of Portland, too. In summer 2014, after landing internships with Complex magazine and Def Jam Records, he connected with a young, unestablished New York City manager named Justin Lehmann. To Hickman, something about the new arrangement set off alarm bells.

“I was with Adam from day one,” he says, “thinking, his success is my success and my success is his success.” Though he won’t dive into specifics—and allows for miscommunications—Hickman says he decided to get his handshake deal with Daniel into writing. Daniel refused. Hickman “got even more weirded out.” The partnership slowly unraveled, taking the pair’s friendship with it, and Hickman would later pull Aminé’s first album and the subsequent En Vogue EP from the internet, asking social media outlets and blogs to do the same. “It was my assumption that he would have most likely taken the music down himself, had I not,” says Hickman.

Aminé’s second full-length album—the excellent, world-music-inspired collection Calling Brio—proved that he was capable of making great music without Hickman. That too has been scrubbed from the web post-“Caroline,” along with videos and articles from 2014 and 2015, as has become standard practice for many indie artists who take on a major-label rebrand. Around the same time, Daniel texted Acuay to ask him to remove all the pieces We Out Here had written about Aminé from the site. Acuay reluctantly agreed. Later, when he saw a national piece on Aminé billed as “the first interview” with the young artist behind “Caroline,” Acuay admits, “I was kind of salty for a second. I had the first interview.”

Two years after Josh Hickman and Adam Daniel parted ways, Aminé struck gold with “Caroline.” The single and video led to a deal with Republic Records, a Universal subsidiary home to artists from Ariana Grande to Black Sabbath. While Daniel moved to Los Angeles in 2016, his official label bio still begins with “Now, Portland isn’t traditionally referred to as a hotbed of hip-hop like Brooklyn or Compton is, but Aminé could very well change that perception.”

For a moment, it appeared that Aminé might force the issue. In November 2016 on Jimmy Fallon’s Tonight Show, Aminé performed a striking and minimal version of “Caroline” with a string section. At the end of the performance, the yellow stage lights switched to red, white, and blue, and he delivered a message to the incoming president elected just days before. “You can never make America great again / All you ever did was make this country hate again.” It was a bold choice, one the Times and other outlets focused on. But Portland music fans noticed something else: two vocalists backing up Aminé were established players in the Portland scene, earthy R&B artist Blossom and inventive MC the Last Artful, Dodgr.

Acuay was watching that night. “It was so very Aminé. ‘I’m not going to do what everyone expects me to do.’ I was really proud of him. I remember thinking, he’s making us look good. He’s really holding it down for Portland right now.”

Publicly, “Go Aminé” is the party line in the Portland hip-hop scene, as well. But there is grumbling behind closed doors. A handful of artists and music scene staples contacted for this story declined to be interviewed about Aminé, or did not respond to requests. One artist formerly associated with Aminé indicated a reluctance to be seen as a hanger-on. A polite decline came from Nikolaus Popp, the prolific Portland director credited as the cinematographer and editor behind the “Caroline” video. Popp sent a somewhat cryptic statement: “Respect is everything in this world and that really goes for any human being. People will try to minimize you, but you always have to know your worth. Money doesn’t pay for respect, no matter the amount. It’s about how you treat people.”

In his first big national profile in the New York Times, Daniel used the phrase “super depressing” to describe his path through the Portland music scene, which the article’s author further characterized as “dead.” Aminé’s lyrical take on Portland has been bittersweet since his earliest songs. And on Good for You, he raps about coming home to find kids who bullied him calling him a hero. In the song “Turf,” he details the city’s gentrification in a mournful chorus: “I look around and I see nothing in my neighborhood / Not satisfied, don’t think I’ll ever wanna stay for good.” Another lyric speaks to those mixed emotions with even more clarity, and perhaps provides an explanation for the artist’s systematic eradication of the old Aminé: “I used to have dreams / Now I dream.”

I asked Vursatyl, one-third of the Portland crew Lifesavas—they released their debut, Spirit in Stone in 2003—if his group experienced a Portland backlash when they surfaced on the national radar. “The difference is we were really trudging it out in the local scene for a long time,” he says. “There were a lot of us trying hard to make it. Some of it was friendly competition, and some wasn’t. But everybody wanted to be the guy to put the city on the map.”

That city—before the gentrification of its North and Northeast quadrants—was a place where the black community was still somewhat centralized, and Aminé’s family home, off NE MLK and Dekum, sat at its heart. “There’s less of a sense of community now,” Vursatyl says. “And I think that, in the long term, Aminé would have benefited from what was the black community still being fully intact. He’s had an awesome journey and he’s doing great, but I feel like there’s a disconnect in terms of local pride in him. And you want that groundswell. You want to play to your base.”

But for Hernandez—who also booked Aminé’s first South by Southwest performance (“The whole showcase fell apart. It was a disaster, actually.”)—the fact that Aminé’s dreams were bigger than his hometown is exactly what made him stand out. “He didn’t make the rounds like other artists, but that’s OK,” she says. “He was building this full package for himself. He didn’t just focus on Portland. A lot of artists put themselves in a box, and that’s cool, but at some point you have to expand. I saw him expand at such an early point, and he’s still expanding.”

Where Aminé is expanding to is an open question. In interviews, he’s low-key and likable—the right mix of confident, humble, and self-deprecating. Critics praised Good for You as “honest” and “carefree.” Its impressive breadth spans from the floaty Frank Ocean-esque Auto-Tune ballad “Hero” to a curious diss track laid out over progressive, minimal electronic music, “STFU.” If anything, the album seems built—albeit on a solid pop-rap foundation—as a showcase for Aminé’s versatility in both sonic approach and personality. He’s a sensitive, brutally honest outcast on the molasses-slow “Sunday,” and a bitter ex-boyfriend on “Wedding Crashers.” Album closer “Beach Boy” spells out the MC’s thoughts on his own mutability: “Who knows what the future holds / I don't, if the truth be told / They say play it safe, young soul / Fuck that, I’mma take control.”

Two years ago, taking control meant parting ways with Josh Hickman, now studying software development in Los Angeles and making music as a hobby. When he won an $18,000 scholarship for making a tutorial video about sampling, Hickman used a song he built for Aminé as the video’s source material. “I took it as a message from the universe or God that, hey, I got what I needed out of that situation,” he says. He hasn’t spoken to Daniel in years, he says, but he’s not bitter about the experience. “We had all these doubts,” he remembers. “We’d be in the studio just talking, saying, ‘Man, are we crazy?’ And it’s dope to see those doubts were unfounded.”

In October, Aminé posted a new video to YouTube, this time for his playful song “Spice Girl.” It hit one million views in three days. The video features a cameo from a childhood hero, from the first concert he ever attended: the Spice Girls’ Mel B. Like every artifact of Aminé’s newly rebooted career, the video is colorful, cinematic, and dreamlike.

The video also makes obvious what should have been clear all along: Aminé never had Portland dreams. He saw himself, a first-generation American-born citizen living in an unlikely corner of the country, playing Madison Square Garden. He saw himself in the company of stars.

Something familiar about the particular inflection Daniel gave the titular “Caroline” suggests she’s the same character André 3000 sang about 15 years ago, on Outkast’s smash-hit “Roses.” In Aminé’s later song “Veggies,” from his 2017 so-called “debut” album Good for You, he refers to himself as “André’s prodigy.” These tributes to the eccentric vocal genius and fashion icon who got every wedding party in America dancing to “Hey Ya” are rare signposts from an artist who seemed, to most fans, to “come out of nowhere.”

Just one year after he uploaded the “Caroline” video to YouTube, Daniel posted a street-corner selfie to Instagram. On the left, wide-eyed with his mouth forming a stunned “ooh,” is Aminé. On the right, Outkast’s André 3000.

Adam Daniel used to have dreams—now he dreams. And his most compelling characteristic seems to be that he’s living out his fantasies in the public sphere. But dreams, by their nature, are not collaborative. They are personal. One dream lived is always another deferred. It’s been clear from the moment “Caroline” hit YouTube that the skinny, gap-toothed kid in the front was going to stay there. It’s still anybody’s guess whom he’ll take with him.