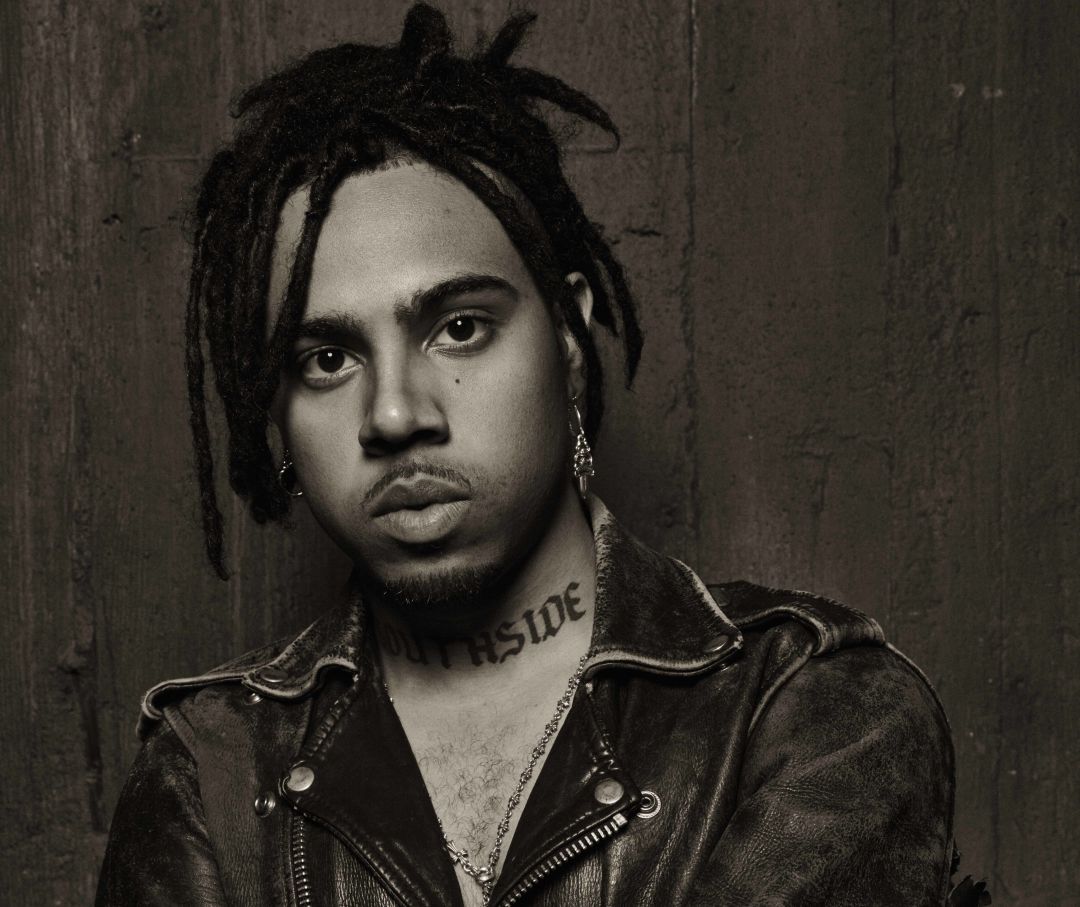

Vic Mensa Talks Police Brutality, Musical Evolution, and Touring with Jay-Z

Image: Frank Ockenfels III

When Brooklyn rapper/mogul/soccer dad Jay-Z announced his tour dates last summer, there were no opening acts associated with the bill, and it raised some questions: which of the many artists on his Roc Nation roster would he tap to warm the crowd? Would he even rely on an opener? Should I buy tickets now, or wait for the inevitable surprise Beyoncé performance (which is definitely not happening) to go viral?

In September, the bill was solidified. Roc Nation/Def Jam artist and Chicago native Vic Mensa would be joining the 31-city tour, and he’s determined to give both core fans and newcomers a memorable experience.

Jay’s 4:44 tour arrives at the Moda Center on December 14, and Mensa has been preparing for what he feels will be his best stage performance to date. His 2013 debut project INNANETAPE was lauded by critics while positioning him as a refreshing young artist to watch. The evolution of the rapper’s sound from the lighthearted “Orange Soda” to the introspective and informed “We Could Be Free” is sonic in nature, but also indicates an increasing need to speak out on behalf of his community, both in and outside of the recording booth.

With the tour already in motion, Mensa took some time out to speak with us about money, “friends,” police brutality, and what he's learned from Jay-Z.

You’ve already accomplished a lot in your career, but what went through your mind when you got that call saying you’ll be going on a nationwide arena tour with Jay-Z?

Get in motion, make it epic, make it legendary. As soon as I found out I was going out on tour, I started putting together the band I had been talking about for some time. More of an ensemble, you know. [It consists of] me, a keyboard player that’s in a little bit of a space station with a couple different keyboards harmonizing the vocals, and another guy that’s playing guitar, MPC, bass.

I started jumping into overdrive to finish the musical direction of my set, which was handled by a really close friend of mine, Peter Cottontale. We started working right around the time my album was released, near the end of the summer. I wanted to lock down and finish immediately, and you know, visual things, like I wanted all of the instruments on the stage to be red. I wanted to do like a really memorable custom look for the tour that was designed by my friend Kerby Jean-Raymond from New York fashion label Pyer Moss. I wanted to do everything in my power to make this a really special experience.

Your latest project, The Autobiography, includes a song entitled “Wings” that includes the line: “Am I still down with the same people that I came in with? Do they value my friendship, or do they just love the attention?” Do you find yourself constantly evaluating your inner circle?

Yeah, man. That is really a constant point of contention being from a situation where not a lot of people have a lot. I talk about it [on] the album—the skit on there is called "Card Cracker." It’s a situation where this guy is playing the role of a friend of mine, saying that I left my credit card out and that they were gonna rob me. That’s a real story! Like, one of my closest friends in the world, and that was real shit that happened in my life, you know? Some of the closest people to me turning and lashing out at me. Stealing from me, lying. So in that song I was thinking out loud and just wondering if I had kept this brotherhood intact, or if I was responsible for the ways and the times where it fell apart.

There is another lyric about blowing a million dollars before turning 24. Is that true? What would you tell your (slightly) younger self about money and the music business?

It is true. One of the things that pops up when you Google any rapper is net worth. That’s one of the first things that pops up when you type in the name of an artist. I never knew as a child what it meant to actually make a million dollars. Yeah, I’ve made millions of dollars. At no point in time have I just had a million dollars, but I’ve made millions of dollars, and clearly spent them, and been taxed, you know? [I’ve] been taxed in the same tax bracket as Bill Gates. When you’re a kid and you hear a million dollars you’re like, “Yo, if I ever made a million I’d be straight for life,” but you don’t even know how much more your cost of living and maintaining and running a business increases the more that you gain.

I guess what Biggie said is true.

One hundred.

You’ve worked with Kanye West in the past. Do you keep in touch with him? Do you have any involvement with his rumored new project?

I haven’t talked to Kanye in a long time, but I got nothing but the utmost love, appreciation, respect, and admiration for him. He’s just one of my idols, point blank. He’s been a huge inspiration. A great mentor and friend to me before and after I met him.

You recently tweeted a pic of you and DJ Drama in the studio. Is there a Gangsta Grillz mixtape coming?

Definitely doing a Gangsta Grillz mixtape.

GANGSTA GRILLZ U BASTARDDSS pic.twitter.com/vS9UHIc4MD

— vino the agitator (@VicMensa) November 14, 2017

You mentioned a while ago that you and Chance the Rapper may have something in the works. What is that relationship like these days?

Yeah we’ve been in the studio a couple times kickin’ shit. That’s my brother. Before music, after music. That’s family.

You’ve been vocal about police brutality in your hometown of Chicago, specifically with the Laquan McDonald shooting. What would you say to people who use the “black on black violence in Chicago” narrative as a response to those protesting police violence against unarmed black civilians?

Black-on-black crime is a myth. In Las Vegas, a white man posted up in a hotel room and killed country music fans—and you know who the country music fans are. When is that described as white-on-white crime? Or Sandy Hook? When is anything that is not in the black community described as “this-on-this” crime? White-on-white crime has never been a term. The majority of crime that happens in America is white people on white people because [they’re] the majority of people in America. Black-on-black crime is an idea that they use to distract you, so that you don’t ask the real questions.

What do you think are the real questions?

Who is profiting from all of these deaths? Who’s profiting from the pain? From the crime? From the mass incarceration of black people? When you start asking those questions, you start finding some really peculiar answers. You know that 1994 crime bill that Bill Clinton put into action with the mandatory minimums and the three-strikes laws that effectively removed judges’ ability to even look at people’s lives and fortunes in a subjective and case-by-case manner? That crime bill was presented by a super PAC that contained the corporations behind privatized prisons. The people that owned the prisons actually presented the law that later went to incarcerate hundred of thousands of black men. Those are the real questions. They’re creating the crime to feed their system of monetary gain from incarceration. Clearly in a capitalistic society, monetary gain is of paramount importance. That is the No. 1 goal of a private citizen. You want more crime to happen, and you want crime cracked down on, so you can make your money. Those are the questions, but they don’t want you to ask those questions, so they tell you “black-on-black crime.”

Going back to The Autobiography, how has working with legendary producer No I. D. influenced your artistic process?

I’ve learned so much working with [him]. Music theory, structure, production and composition of an album. I’ve learned things about, like, relative major and minor keys. I really had the majority of the songs written and then I would bring them to No I. D. and get his take and his input on what he was into, what he wasn’t as into, and we reimagined a lot of the records.

[A track] might’ve been brighter at first, and then No I. D. was like, "Well, we can keep it in the same key, same tempo and everything, maybe speed it up or slow it down a little bit, but make it darker." That’s how I learned about relative minors. [Also] having consistent sounds. No I. D. is a real gear junkie. Like a real studio guru, in a classic sense, as a producer. That was really dope for me because I’m really into vintage gear and shit like that too. Just, like, tangible synthesizers, you know. Real instruments. o we used a lot of the same keyboards and major pieces all through the album. Centralizing the sounds of the drums. Even though I go through so many different styles at times, [the album] still feels cohesive. It still feels like one body of work. No I. D. was really instrumental in making that.

Portland has been a tour stop for you in the past. Have you had a chance to hang out here? Any favorite spots to visit?

I fucks with Portland. I remember going down to Portland to do an Adidas Christmas party a long time ago. That was really fuckin’ dope. I don’t think I’ve really experienced the nightlife or the spots in Portland. I just always have a good time at the performances. I feel like the crowds are live.

What can fans expect from you on the 4:44 tour?

I feel like this is definitely my best performance to date, and I put a lot of time, effort, heart, and soul into my set. The musical direction, the ebb and flow. I think you come away from this concert with real tools in hand, if you choose to use them. We’re asking real questions and starting real conversations that can be bigger than music.

Last question: what's one thing you’ve learned from Jay-Z?

I learned that you’re six years old in first grade. You know when he said, “'Cause the boy got more 6's than first grade?” When I was a kid, I didn’t know what a 6 [600 Class Mercedes Benz] was. I didn’t know it was a car. That’s always my point of reference when I think about how old kids are. I just know you’re six years old in first grade.

Jay-Z with Vic Mensa

8 p.m. Thu, Dec 14, Moda Center, $27.50+