How Maps, Migration, and Soccer Inspire Artist Ronny Quevedo

When he was a kid, Ronny Quevedo moved with his family from Guayaquil, Ecuador, to New York City. Growing up, he’d watch his father—a former pro soccer player in Ecuador—referee games for majority-migrant communities. In these arenas, Quevedo absorbed the game from the referee’s perspective, taking in rules and boundaries potentially overlooked by the casual spectator.

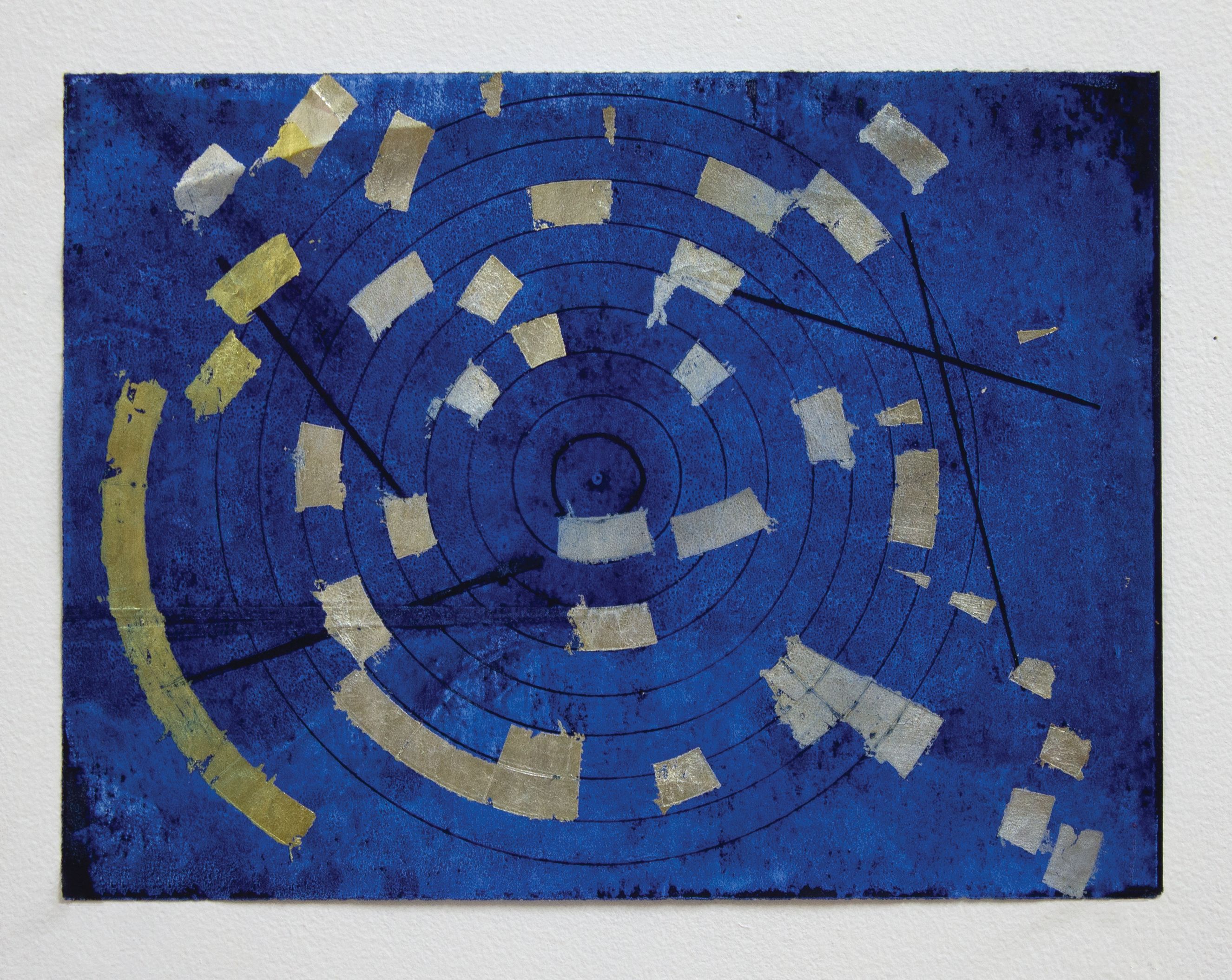

Several decades later and now working as an artist in New York, Quevedo has been able to translate those experiences to paper. Take one work, Cancha de Nazca, in which sharp, straight lines criss-cross a blue playing field, creating a sense of motion and urgency. The piece evokes the high stakes of a close soccer game, or perhaps the anxiety of moving through Midtown on a CitiBike at 5:30 in the afternoon.

That sense of motion is central to Quevedo’s work. Through mark-making and embossing, his images depict a sometimes chaotic sense of movement; his work has been said to evoke maps or migration lines. That rings true for Quevedo, who says he wants the viewer to consider this idea of multiplicity, “of being in one place or of many identities at the same time and how various perspectives can influence our readings of supposedly neutral ideas."

Every Measure of Zero, a solo exhibit, opens at Upfor Gallery March 7 and runs through April 27. In advance of the show, we talked with Quevedo about abstraction, mapping, and the connections between migration and soccer.

Can you tell me more about this show?

The exhibition revolves around a series of works that I’ve been developing over the year. The idea [of “every measure of zero”] stems from the writings of Édouard Glissant, but also thinking about identity as a place of multiple starting points or multiple origins. So what I’ve been doing is taking this idea of multiplicity and reworking certain notions of mapping and space—globes and playing fields especially. To think about how that answer sets with my own life, my own biography, and thinking about how that plays out when it comes to constant measuring or the idea of sense of locality within specific sights.

Can you give an example?

As an example, the idea of the south and the north being in opposition to one another while simultaneously existing. This idea also branches out into what’s in the center, what’s on the periphery. And that’s where it connects a little bit more to the work of Édouard Glissant. He was always questioning the idea of what it is to be on the margins. And how the margins are always in touch with the center, and there’s this constant flow of the center with the margins and with the periphery.

When did you discover Glissant? What drew you to his work?

I’ve been thinking about his work for a long time. With this series of works, some of the imagery is recognizable but not immediately. It lends itself to a bit more abstraction. It’s more removed from its original association. So while I’m interested in people reading them as maps and globes, I think they’re at a point where this abstraction is a bit broader.

Your father was a soccer player and there are a lot of playing field themes in your work. How did that develop?

My dad was a professional soccer player in Ecuador in the late ’50s, early ’60s. He was a first division player. This was definitely before players were making the money that they’re making now, so it was very much a labor of love. He was immersed in it. When we moved to the States, he took that on as more of a recreational thing and started doing a lot more refereeing. He was a referee both in the summer and the wintertime for indoor soccer leagues. As a kid growing up, I got to see the whole aspect of the game of soccer. It’s unusual to think about the game as a referee but it was something I was really close to because of my dad. So my connection to sports is really thinking about it very holistically and taking in the whole environment. I think about the convening and collective actions of both sides, even the referee, so it’s very much having grown up with sports around me, but also soccer leagues and public parks.

Your work has been said to evoke migration lines. Does that resonate with you?

When we would go to [the indoor soccer leagues], they were made up of majority-migrant communities who were working during the week but on the weekends would establish these very well-organized teams with uniforms and rules and set parameters of how the league would function. So when I think about the field, I think about the movement of bodies from one place to another and connecting that to a sense of identity, of always shifting from one place and having to acclimate to another. Similar to when you’re given a set of parameters within the bounds of the field, it’s kind of thinking about migration in that sense. Where coming into a new culture, a new space, and a new geography, you’re oftentimes prescribed a certain role. I’m really thinking about the movement within the field as a way of how we negotiate all these rules that we want to be aligned with, but also how we need to innovate and navigate that space to claim our own identity.

Ronny Quevedo

Mar 7–Apr 27, Upfor Gallery, FREE