For Hank Willis Thomas, All Art Is Political

The Cotton Bowl (2011)

Image: Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis Thomas isn’t afraid to admit he cares what you think about his art. “If everyone was indifferent, you would not be making art,” says Thomas. Art, after all, creates conversations, and conversations are the prequel to change. The New York–based conceptual artist has spent his career insisting the fine arts belong to everyone, and his work, which is often interactive, explores popular culture and prods at inequality, identity, racism, and violence, using materials like prison uniforms, neon signs, and mirrors. Outside the studio, with an initiative called For Freedoms, he joins with artists and others to urge civic activism via billboard campaigns and town hall meetings.

In October, a survey by the 43-year-old titled All Things Being Equal... opens at the Portland Art Museum. (After this inaugural stop, it’ll travel to Arkansas and Ohio.) It’s a plum opportunity to see Thomas’s dizzying range in full: the exhibit’s 100 or so works range from quilts stitched from sports jerseys to vintage ads stripped of their text to a huge new flag-based piece memorializing lives lost to gun violence in 2018.

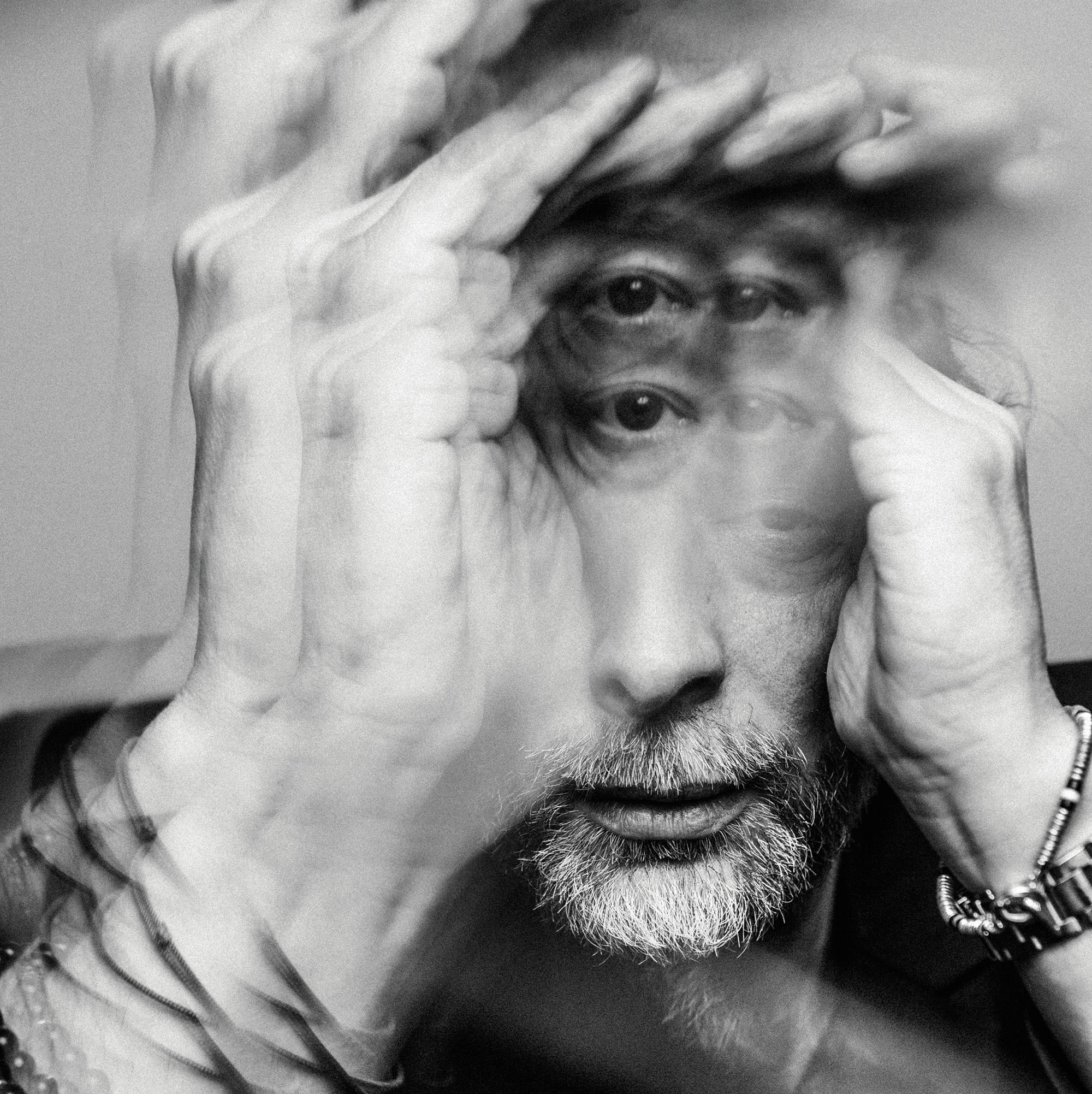

Branded Head (2003)

Image: Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas

The exhibit pulls its title from an aluminum sculpture you made in 2010. How did that come to be the name of the show?

The work itself is really intended, as most of my work is, to ask a question more than it is to make a statement. The ellipsis implies that whatever follows after that statement will conclude it. The question is, how do we conclude the pursuit of liberty, justice, and equality for all? And to me, I think that’s a perennial, unanswered question.

Your work addresses the commodification of black male athletes within a predominantly white-owned and -run sports industry. What’s the significance of this show opening in Portland, home to Nike’s global headquarters and Adidas’s North American headquarters?

I did get to tour Nike and have had some conversations with people at Adidas and Wieden & Kennedy, all of which are major influences on global culture and my life personally. I think a lot of what my work is trying to do is reconcile the legacy and history of commodity that included bodies of African Americans as commodities, with our contemporary system.... My agenda isn’t necessarily anticorporate, but it’s much more trying to ask the question of how does history repeat itself, and how do we consider addressing long, systemic issues in the contemporary age?

A Place to Call Home (2009)

Image: Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas

What prompted you to dissect visual culture in your work?

My mother, Deborah Willis, she’s a photographer and art historian, a curator, and her life focus has been really about re-presenting and reconsidering representation of people of African descent in photography, but also looking at the way in which African Americans often made images that countered and disrupted stereotypes.... I learned, probably through osmosis more than anything, that what lies beyond the borders of any photograph is more important in some ways than what is captured within the frame. A photograph is a split second of time capturing a very narrow-angle view in two-dimensional space, and we suspend our disbelief into making that a representation of reality.

Where are you currently finding inspiration?

Well, as you can hear in the background, I have a five-month-old baby, so that’s a source of inspiration. Seeing how much the world has changed in my lifetime, I’m thinking about, wow, how will it be for her and what responsibility do I have to her?

Strike (2018)

Image: Courtesy Hank Willis Thomas

Art and politics are inextricable in your work. Have you seen the political function of art change over your career?

I’ve come to consider all art as political and therefore have been reconsidering the entire way I relate to art and art history, because most of what we know about past cultures is through art. What our society is producing and what it’s discarding—it’s important. What happens in museums and is preserved for future generations is incredibly powerful and incredibly effective on a political level as well.... We [at For Freedoms] believe museums are civic spaces and that artists should be seen as civic leaders, because these are the places where ideas that inform and, in many ways, shape our society are built and preserved. The fact that we don’t necessarily acknowledge [this role of the arts] is why oftentimes arts and culture is first on the chopping block when it comes to budgets. Sadly, we live in a society where we think we can solve major entrenched issues without creativity.