The Bizarre History of the Maryhill Museum of Art

A dancer, a philanthropist, a railroad executive, and the queen of Romania walk into a bar. They come out with a Rodin collection and a political text that would sit well with most socialists.

Situated on a bluff in the Columbia River Gorge about two hours east of Portland, the Maryhill Museum of Art was preparing to celebrate its 80th birthday this spring. Steve Grafe, its curator of art, had planned an exhibition on European textiles in a nod to the institution’s Romanian roots. There were supposed to be screenings and panels and retrospectives, all honoring the remarkable persistence of perhaps the Northwest’s strangest museum—a Beaux-Arts mansion that sports not only early sketches, plasters, and bronzes from Auguste Rodin, but a hefty collection of Native art, copious Greek and Russian icons, 400-plus chess sets, and fashion miniatures straight from the Louvre.

Then ... you know. Typically open March to November, the museum (like so much else) is closed until further notice.

COVID-19 is hardly Maryhill’s first curveball. The history of the museum is a history of interruptions. By the time it opened in 1940, 14 years had passed since the building’s dedication, and its founders had been dead a decade.

“There is a dream built into this place,” said Queen Marie of Romania during her dedication address on November 3, 1926 (the same day Annie Oakley died of pneumonia in Ohio). And there was. It just took a little while to surface.

At the turn of the 20th century, Samuel Hill and Loïe Fuller were on top of the world. Hill was a midwestern railroad man who had just purchased 5,300 acres of land at a remote edge of Washington state to establish a Quaker community called Maryhill, named after his daughter. Fuller had fled America for France, where she helped define an entire era of contemporary dance and ingratiated herself with artistic and intellectual gentry, from Alexandre Dumas to Marie Curie. The pair first met in Paris, where Fuller introduced Hill to Rodin and persuaded him to buy some early works.

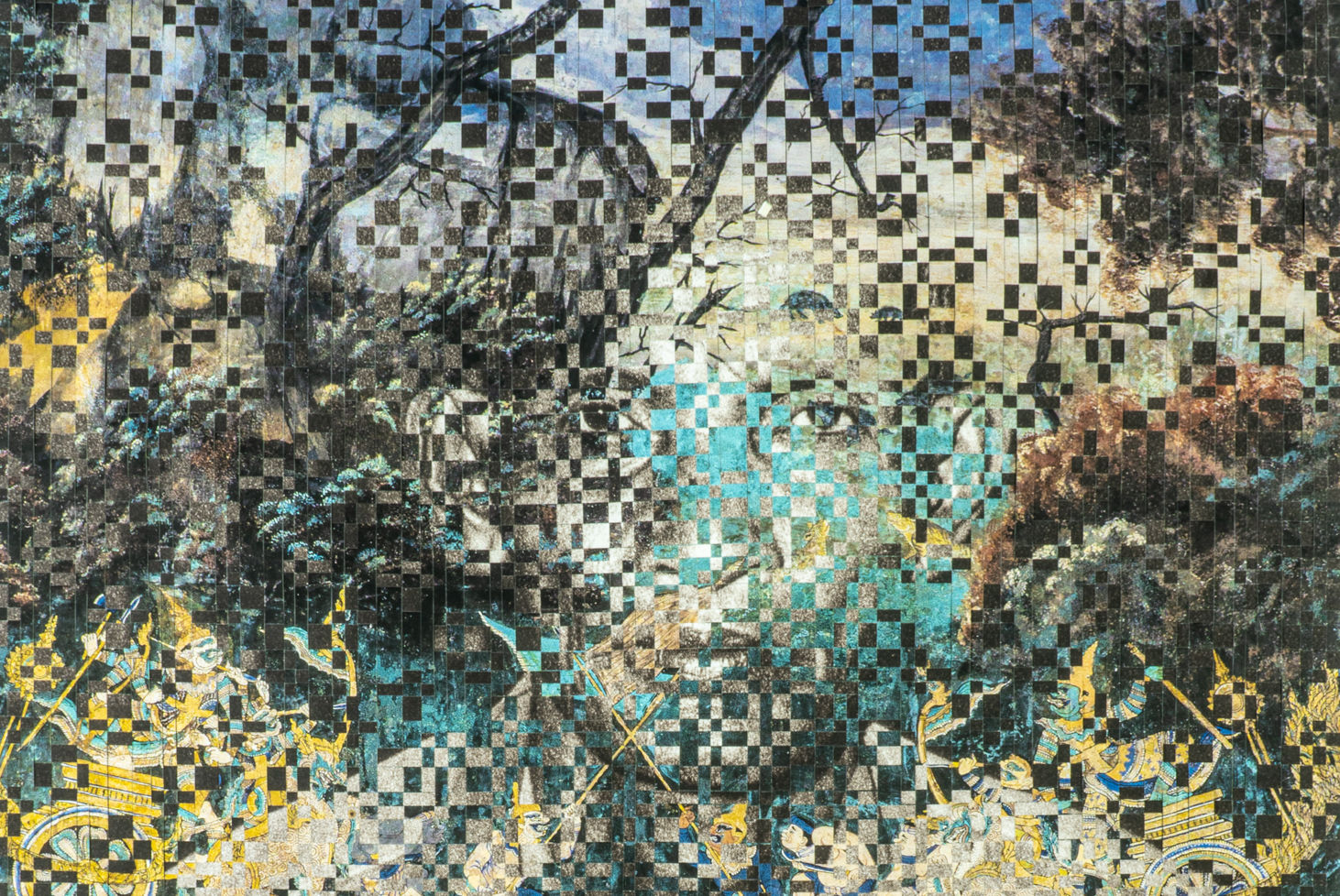

Image: Mike Novak

Over the years, Fuller and Hill stayed in touch. Hill’s plans for a quiet agricultural community went up in literal flames some time in the early 1910s, when a fire swept through the region and burned his nascent town to the ground. Still, he started building a clean-lined modern mansion in the ruins of Maryhill to house himself, his wife, and their daughter. Fuller nudged him to reimagine the space as an art museum, filled with European work, and it was her connections that eventually kept the museum full.

“After the eloquent pleading of today, I have decided to dedicate my new chateau at Maryhill, Washington, to a museum for public good, and for the betterment of French art in the far Northwest of America,” Hill wrote to Fuller in July 1917. “Your hopes and ideals shall be fulfilled, my dear little artist woman.” (Fuller was gay and had taken a long-term lover in France, which casts hers and Hill’s lengthy correspondence in a fairly platonic light.)

Hill and Fuller’s pursuit dovetailed with a similar story on the opposite coast: in Boston, eccentric socialite Isabella Stewart Gardner had collected art from across the world to stow in her empty Fenway mansion, decrying America’s lack of appreciation for the European masters. She opened the space in 1903 as a multilevel museum, stipulating in her will that no object be moved from its place when she passed. Decades later, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum—whose whimsy remains in the form of company policies that, for example, admit patrons named Isabella for free—became the site of the world’s most expensive unsolved art heist. Thirteen pieces lifted without a single compelling suspect. Rembrandts and Vermeers cut ruthlessly out of their frames. There was a podcast about it.

Image: Courtesy Maryhill Museum

Nothing quite so sexy ever happened at Maryhill, and maybe that accounts for its comparative under-the-radar status, despite some thematic overlap. Perhaps, also, it’s difficult to gather much cultural clout when you’re situated on a secluded segment of the Oregon-Washington border with no restaurants or commerce for miles (aside from some highway food and services across the Columbia at Biggs Junction), in the midst of an abandoned, unincorporated community that never grew into the Quaker paradise it was designed to become.

Image: Courtesy Neeson Hsu

These problems were not lost on Sam Hill, who served as president of the Washington Good Roads Association and was a major player in the inception of the Columbia River Highway. Unsuccessfully, he bid for that project to cut past Maryhill on the Washington side of the Gorge, providing scenic views of the region he’d come to love and easy access for tourists to marvel at the fruits of his and Fuller’s labor. “You can’t survey a road along the Columbia River, let alone build one,” Washington highway commissioner James Allen told Hill as his idea gathered steam after World War I. So he pursued Oregon’s then-governor Oswald West instead, eventually establishing the Columbia River Highway on the Oregon side of the Gorge and settling for Washington State Route 14 as an automobile connection to Maryhill.

As Fuller and Hill’s plans grew more fevered, they drew up a manifesto for their still-unfinished museum. The resulting 20-page document, titled Idea, Desires and Purpose of the Maryhill Museum of Fine Arts, bears very little resemblance to Hill’s outspoken Republican politics. It frames Maryhill as “a direct union which could not be disturbed by the introduction of hidden influences for political or monetary gain, or to be broken off by international strife. A permanent union of peoples through art, education and a united effort for the betterment of each.” It calls for the formation of an international delegation and for worldwide, Maryhill-sponsored art competitions; it invokes the names of czars and painters from Serbian portraitist Paja Jovanović to Spanish master Federico Beltrán Masses.

Image: Courtesy Maryhill Museum

In total, it makes up the “dream” Queen Marie would later cite at her dedication address. Like many of Hill’s dreams, it was fuzzy, zealous, and smelled lightly of mania: in 1918, he commissioned a replica of Stonehenge three miles east of his mansion-museum, a WWI memorial that would serve “as a reminder that humanity is still being sacrificed to the god of war.” (The original Stonehenge was not, in fact, used for human sacrifice.)

Fuller and Queen Marie had begun a close friendship in France, and the dancer persuaded the monarch (Romania’s last queen) to make her first visit to America and dedicate Maryhill, even though, at the time, it remained little more than a skeletal structure. As a testament to Fuller’s effusive charm, Marie agreed, and rode the train to Hill’s mansion with $2 million worth of textiles and icons in tow. Privately, she expressed dismay: “Dear old Sam really is a freak and all he does, builds, or invents is freakish,” she wrote in her diary on the trip. “I knew when I set out to consecrate that queer freak of a building that no one would understand why; I knew it was empty and in no wise ready to house objects for a museum.”

Still, her November 3 address was full of hope and bluster. “Sam Hill is my friend. He is not only a dreamer but he is a worker,” she said to the assembled crowd of about 2,000, including reporters from the New York Times. “So when Samuel Hill asked me to come, I came with love.”

Two years after the queen’s address, Fuller died of pneumonia in Paris, just shy of her 66th birthday. The museum remained in Hill’s hands, where it got tied up in financial troubles. He died three years later, in 1931, after falling ill en route to lobby the Oregon Legislature about preserving local highways.

Maryhill would have languished had Hill’s friend, the six-foot-tall San Francisco philanthropist Alma de Bretteville Spreckels (“Big Alma” to her friends), not picked up the gauntlet. In 1921, she’d created a Maryhill of her own in San Francisco’s Palace of the Legion of Honor, a replica of the French Pavilion that she filled with her personal art collection. Six years after Hill’s death, she joined Maryhill’s board of trustees, donated pieces from the Legion of Honor to fill out its permanent collection, and shepherded the institution through financial hurdles until it opened to the public on May 13, 1940. Queen Marie missed it by two years, succumbing to cirrhosis of the liver in the summer of 1938.

Image: Mike Novak

Colleen Schafroth started working in the museum’s education department some 40 years ago, seeking arts employment after studio study in Corvallis. She almost left the institution partway through her tenure, but today she’s its executive director, a title she’s held since 2001. Since then she’s expanded Maryhill’s education programs and overseen a $10 million physical expansion.

“It’s become my life,” she admits, explaining that Maryhill has thrust her into international circles despite the fact that she’s hardly helming the Met.

She also notes the majority of the land surrounding the museum remains untouched. Idea, Desires and Purpose ends with an addendum that sits alone on the final page: “The Museum is surrounded with 7,000 acres of cultivated land which in part provide special facilities for those who, once there, would decide to remain. Thus, little by little, an intellectual colony of real workers could become founders of a future city.” It’s easy to read as a desperate final stab at Sam Hill’s perfect Quaker colony. It’s also easy to read as a hopeful gasp in a suffocating world that’s lost sight of community.

Maybe it’s both. Maybe Maryhill is, too.