The First Recorded Reading of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl Took Place in Portland. Now You Can Own It on Vinyl.

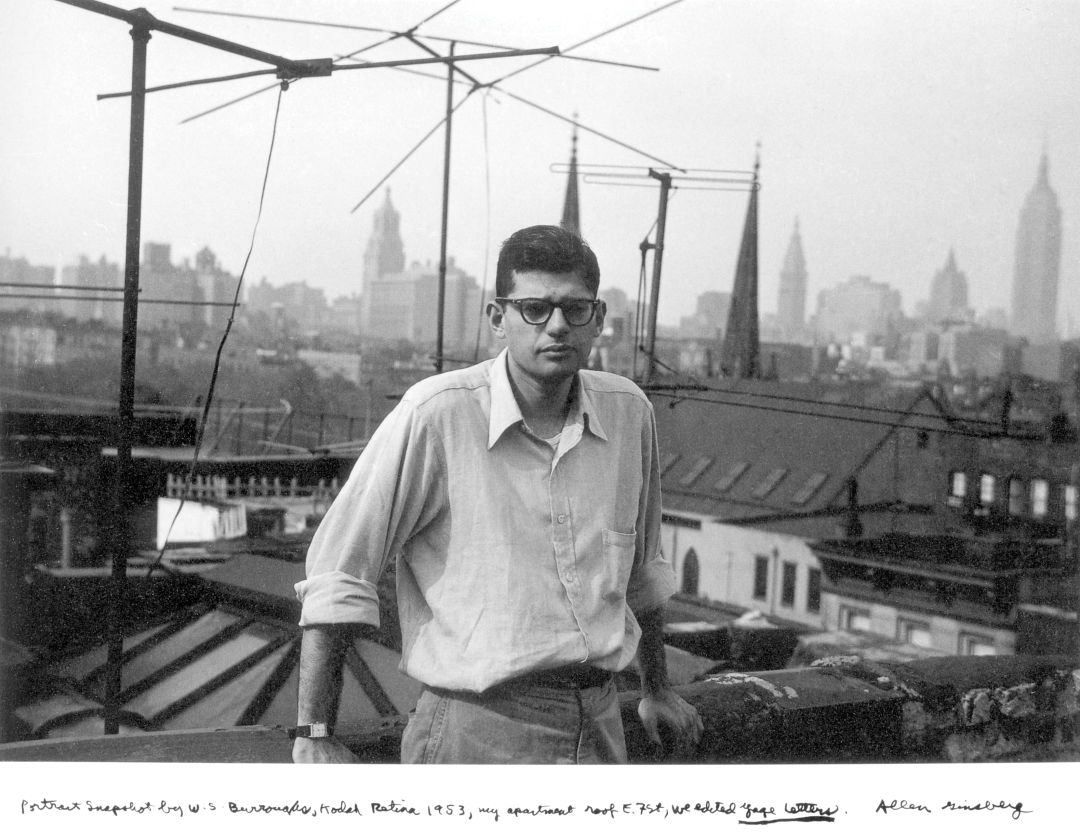

Ginsberg in New York City in 1953

The first time Allen Ginsberg read Howl was at 1955’s legendary Six Gallery in San Francisco—one of the earliest events of the Beat movement. The first time anybody thought to record him reading it was at an informal performance in Reed College’s Anna Mann Cottage, four months later. Ginsberg accompanied poet Gary Snyder to Portland for two nights in February 1956, and the second was recorded on a tape deck, then lost to time, until a Reed professor discovered the tapes in 2007. They’ve lived in the college archives ever since.

“When my wife Audrey became the president of Reed College, we went to a women’s rugby game, and a wonderful guy came up next to me, and we just started talking about music and records and releases,” says record producer Cheryl Pawelski. “And he said, ‘You know, the first recorded version of Howl by Allen Ginsberg happened here.’ And my radar just went off.”

Pawelski is a cofounder of Omnivore Recordings, a record label that specializes in historical releases and reissues. (Omnivore's 2019 release, It’s Such a Good Feeling: The Best of Mister Rogers, won the Best Historical Album Grammy last month.) She had worked with the Ginsberg estate twice before her colleague alerted her to the Howl tapes, and suspected they’d be game for a third collaboration. She was right. On April 2, Omnivore will release At Reed College: The First Recorded Reading of Howl and Other Poems on vinyl, CD, and digital platforms. A limited-edition "Reed red" vinyl will be available at the Reed bookstore; it's already sold out online.

To transfer and restore the tapes, Pawelski tapped audio engineer Michael Graves, whom she first worked with on Omnivore's Grammy-winning 2014 release Hank Williams: The Garden Spot Programs, 1950. "When you're working in the historical field ... there are some things that would just be lost to history if you didn't have somebody who could restore it," she says. "I'd been frustrated in the past by [projects] that I knew in my head were possible, I just didn't have the person with the know-how and audio gizmos." She met Graves through the Recording Academy, he supplied the necessary gizmos, and a fruitful creative partnership was born.

Pawelski shipped the Howl tapes from Reed to Grave’s studio in LA (“It’s nerve-wracking at first, but we’ve never lost tapes before,” Graves says), where he restored and digitized them. Graves is used to working with vinyl, which typically carries a lot of surface noise, but he says the Howl audio came to him in excellent condition.

“There was some tape hiss on there, but there was also a lot of really great room ambiance. There’s some point where the air conditioner kicks on … that had to be left in. And one of my favorite things is [Ginsberg] doesn’t actually finish Howl. He says, ‘Oh, can I stop here?’ and you hear this big kerplunk of the tape when he stops. And we left that in, because it’s such a great ending," Graves says. (Ginsberg read Howl in its entirety on his first night at Reed; on the second, recorded night, he stopped during part two of the three-part poem. “[Howl] exacts an emotional and physical toll,” Pawelski says. “He was tired.”)

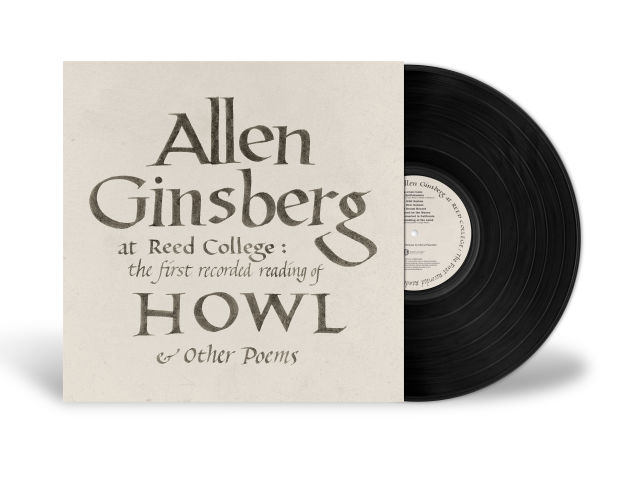

At Reed College: The First Recorded Reading of Howl and Other Poems on vinyl, with jacket design by Gregory MacNoughton

Image: Courtesy Omnivore Recordings

The tapes also include seven other poems, a few of which (like "A Supermarket in California" and "Transcription for Organ Music") were published in the first edition of Howl and Other Poems. In all, the Omnivore album runs 11 tracks and 35 minutes. Due to a dearth of photographs of or paraphernalia from the event, Pawelski asked a colleague to draw up the album art in calligraphy, which she says has “a strong history” at Reed.

Reflecting on Omniovre’s work, Pawelski says, “If something is sitting on a shelf somewhere, or on a piece of shellack, that’s not shareable. By making a 1,000 of something, it has a better chance of lasting.” With two Grammys under her belt, she’s about to kick open the doors on what might be one of the most consequential bits of poetry paraphernalia of the 20th century, and she knows it. “It’s like we’re throwing things into the future for people to find.”