‘An Assembly’ Builds a Play with 12 Strangers and a Stack of Notecards

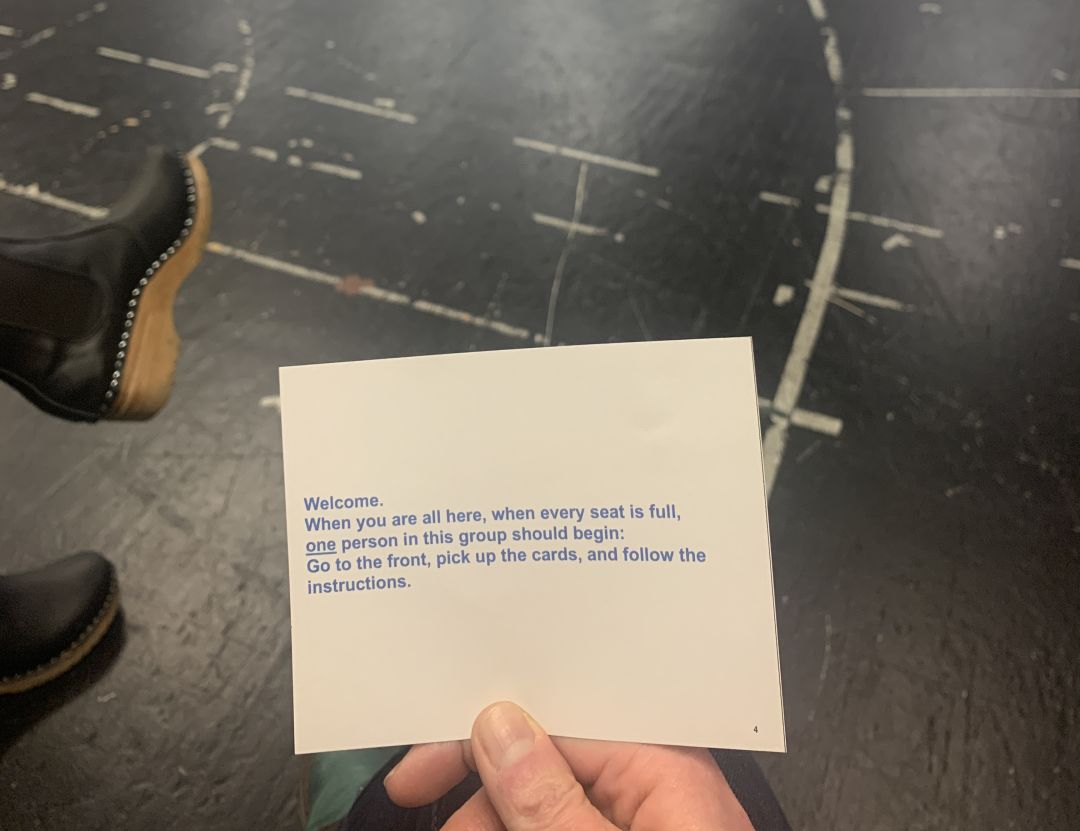

The initial prompt in "An Assembly"

Image: Rebecca Jacobson

One by one, ushers lead us into a spartan, fluorescent-lit room at the old Zidell shipyards. In the OHSU gym opposite, tiny figures jog on treadmills. Evening traffic on the Ross Island Bridge hums dully in the background. There’s a table for our belongings, a rack for our coats. Twelve black chairs form two rows. On each seat rests a notecard:

Welcome.

When you are all here, when every seat is full,

one person in this group should begin:

Go to the front, pick up the cards, and follow the

instructions.

So launches the latest show from Abigail Browde and Michael Silverstone, the experimental New York–based theater duo known as 600 Highwaymen. It’s the third and final part in a series, titled A Thousand Ways, that Browde and Silverstone have been developing over the course of the pandemic. It began with “A Phone Call”: an hourlong phone conversation between two strangers, guided by an automated voice. Next came “An Encounter,” in which two strangers met at a table across a shield of plexiglass. Now is “An Assembly,” which brings together a group of strangers with only a stack of notecards to steer them.

It’s a simple proposition, but a risky one. People dread audience participation for a reason, and full-blown participatory theater, where audience and performers are one and the same, can easily slide into the hokey or didactic. Sometimes it tips right off the deep end: I once found myself in a room with an audience member who, seemingly out of frustration with the show’s poky pace, squawked and picked around the perimeter like a chicken. Another woman lit a page of the script on fire, watched it burn in her hand, and then tossed it in a trash can and exited the theater.

When you’re not in the room—and Browde and Silverstone aren’t for “An Assembly”—how do you actually get audience members to do what you want them to do? According to Silverstone, it’s harder than it seems. That became clear in Colorado Springs late this summer, when the duo began building “An Assembly.”

“We could not figure out how to get the group to do anything but sit,” Silverstone told me, speaking by phone earlier this week.

Which is what brings 600 Highwaymen to Portland: to figure out, among other things, how to get a group to do anything but sit. Portland, where the duo is being hosted by Boom Arts, is just the second stop in the development phase of “An Assembly.” And audiences here, Silverstone said, are getting “a completely different show” than what went down in Colorado.

That show, at least as I experienced it on Tuesday (it continues Friday and Saturday), is a gently probing, occasionally awkward, surprisingly tender piece of theater. A big change Browde and Silverstone made was to drop audience size: in Colorado, the crowd counted as many as 40. On Tuesday, we were just a dozen, and it didn’t take long after finding our seats for one of us, a lean gray-haired man, to spring to the front of the room and pick up the notecards from the piece of plywood on which they sat. He stood in front of the plywood—I suspect Browde and Silverstone had hoped us to stand on the plywood, as if it were the stage—and began to read from the cards.

We raised our hands as the cards led us through questions: Who has children? Who is in physical pain? Who is worried? At some point we stood (count that as a win for Browde and Silverstone) and formed a circle, answering more questions: Who still has their wisdom teeth? Their tonsils? Who is a doctor? A teacher? Who has been to Paris? At another point we clustered in different parts of the room—stand here if you were born in Portland (one of us), here if you’ve had an organ transplant (none of us), here if you’re at a crossroads (fully half of us). Somewhere in the middle of the hour, one audience member closed her eyes and described her outfit. In a moment that prompted anxious glances over our masks, one card asked us to place a hand on the person we deemed most trustworthy. I found myself searching for an expression of consent, relieved when another audience member made reassuring eye contact with me. She placed her hand on my shoulder, and I placed mine on hers.

The cards moved from one audience member to another. When they landed in my hands, I had to guide the group to form chairs into two rows facing each other, a catwalk running down the middle. A few moments felt like play, as when we pulled at a spool of thread to make a giant circle, or, toward the end, when we joined our voices for a few lines of “Only Fools Rush In.”

Throughout, the text took brief imagistic flights, asking us to imagine a green lawn, clouds of dust, desiccated earth, or blades of grass as fine as eyelashes. These parts of the script, Silverstone later explained to me, stem from the duo’s recent fascination with the Dust Bowl—they see parallels between that years-long period of catastrophe and our present moment—and from having spent much of the pandemic away from their New York City home in a rural part of the state. The change in surroundings has spurred reflection, he said, “about the landscape and about our smallness.”

He went on: “The other thing we’re trying to work on is this idea of something that feels like it’s over, but it isn’t—and how hope works.”

What it means to gather after protracted isolation, how it feels to weather a seemingly unrelenting storm, the tininess of humans, the mechanisms of hope—it’s a lot to squeeze into an hourlong show that depends upon the cooperation of a group of strangers. Tuesday evening had a bit of a throw-the-spaghetti-at-the-wall feeling, and Silverstone said he and Browde had spent the following day making all sorts of tweaks to the script. The development phase isn’t over, either. Next month, the show will travel to Williams College in western Massachusetts, and then to the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston.

But let’s be clear: much of the spaghetti thrown on Tuesday stuck. The show felt inquisitive rather than invasive, and by the end, with nearly all the notecards strewn across the floor, I did feel a certain intimacy, a soft pulse of kinship, among our group. As for the awkward moments—the anxious asides from audience members, the attempts to pull a face behind a mask, the nervous titters—those felt like an important part of it, too.

A Thousand Ways: An Assembly

7 p.m. Fri, 2 & 7:30 p.m. Sat, Nov 19–20, Old Moody Building, $20–45