The Best Oregon-Made Movies, Books, Music & Art of 2021

Photograph of Ithica Tell in Sanctuaries courtesy Intisar Abioto

For a year that promised the great return of the arts, 2021 sometimes felt like an anticlimax. Vaccines arrived, things got better, we quickly learned that “better” is different from “over,” and the goalposts moved so often that it seemed we could never quite decide just how “back” we were.

If that confusion is all we remember about this year, though, it will be a shame. However compromised, we did get to gather again—the galleries opened, the shows went on, and we found ways to experience art beside friends and strangers alike. It was a salve, if not a cure, and plenty of local talents stepped up to the plate and delivered. These were a few of our favorites.

Image: neon

FILM: Pig On paper, Pig sounded like a classic slice of loopy Nic Cage pulp fiction. “An Oregon forager descends into Portland’s criminal underbelly to break some bones when his beloved truffle pig goes missing.” What first-time writer-director Michael Sarnoski delivered, though, was softer, stranger, and altogether more memorable. As a self-exiled celebrity chef, Cage is fragile, funny, and human beneath cakes of blood and the scraggliest onscreen beard since Leo’s in The Revenant; as a truffle supplier with an ill-fitting Camaro, Alex Wolff is his petulant and heartbreaking foil.

The movie thrives on their dynamic and its own gonzo structure, which sometimes crams several tones into a single scene, and effectively harnesses Portland’s present identity crisis to paint a mythic portrait of the Rose City as a place of brutal contradictions. By the time Pig folds in grief to its thematic omelet, it could feel like a weak stab at credibility, but Sarnoski sticks the landing and pulls off one of the best, most affecting films of the year, Oregon-made or otherwise. —Conner Reed

Image: Beacon Sound

MUSIC: Body of Water by Dolphin Midwives What, you might ask, would it sound like if FKA twigs lived under the sea or Björk were more into whispering? Now you have your answer. Body of Water is the second full-length LP from Portland harpist-producer Sage Fisher, who records as Dolphin Midwives. Compared to Fisher’s debut, 2019’s Liminal Garden, Body of Water is a decisive step toward pop, which is not saying much. Like the songs on Liminal, these tracks fracture and gurgle and hiss, their sunny sonics giving way to storm clouds (and vice versa) throughout. Unlike on that earlier album, though, Fisher’s voice is a major presence here, and you could, in theory, listen to several of these songs in isolation and be satisfied.

Really, though, Body of Water is best heard as a whole: it washes over you, shepherding you through moments of dissonance and discomfort toward brushes with the sublime. By the time Fisher brings you home with “Sunbathing,” don’t be surprised if you find yourself tearing up. —CR

Emmanuel Henreid in Sanctuaries

Image: intisar abioto

PERFORMANCE: Sanctuaries at Third Angle New Music Third Angle’s Sanctuaries was, among other things, a thrilling assembly of some of the city’s best cross-discipline talent. Composed by beloved local musician Darrell Grant, with a libretto by Oregon poet laureate Anis Mojgani, the six-years-in-the-making jazz opera featured Damien Geter (the interim director of the Portland Opera, who has performed at the Met), Emmanuel Henreid (who went viral in 2020 for his impromptu duet of the national anthem with a Portland State student), Ithica Tell (an award-winning stage and screen actor), and Marilyn Keller (a stalwart Portland jazz vocalist with beyond-golden pipes).

The piece’s subject matter—gentrification, Black subjugation and resilience, the power of communal memory—couldn’t have been more relevant, especially as performed outside the Veterans Memorial Coliseum, which was built on the razed homes of a once-predominately Black neighborhood. But a production is more than its subject matter, and this one was indelible for its mastery.

Mojgani’s dizzying language reveals with one hand while concealing with another, constantly forcing the audience to lean in; Grant’s music is a provocative fusion of jazz, soul, and traditional chamber music. The staging, by LA’s Alexander Gedeon, evoked the occult (a sense reinforced by Carl Faber’s dreamlike handheld lighting design), and after 80 thrilling, challenging minutes of excavation, Sanctuaries turned to us and said, “What are you going to do with all this?” Every “topical” project should be so bold. —CR

Image: Allyson Riggs/Hulu

TELEVISION: Shrill Aidy Bryant wasn’t ready to say goodbye to Shrill, her Portland-set comedy that ran for three seasons on Hulu before ending in spring 2021 on an achingly familiar note of uncertainty that will resonate for anyone who has ever felt lost in their 20s (read: all of us).

Unlike that other Portland-set show that shall not be named, Shrill never really trafficked in Rose City grain-of-truth-uncomfortable stereotypes. Instead, it lavished love on us, with pivotal scenes shot at the St. Johns Bridge, Oaks Amusement Park, and in and around NE Alberta Street. There’s something terribly wistful about watching the show now—its Portland is a prepandemic time capsule, though the final season did dive into the city’s current tortured conversation about how virtue-signaling white people talk (and don’t) about race.

Like Tony Soprano and Walter White before her, Bryant’s Annie was allowed to be deeply flawed—she can be insufferably sanctimonious in one scene and come correct in another—and we root for her accordingly, even at her most haphazard. Unlike those two archetypal antiheroes, her story ended before she could say a proper farewell, so let’s say it loud now, on behalf of Portland: goodbye to Shrill—and thank you for being among the year’s very best. —Julia Silverman

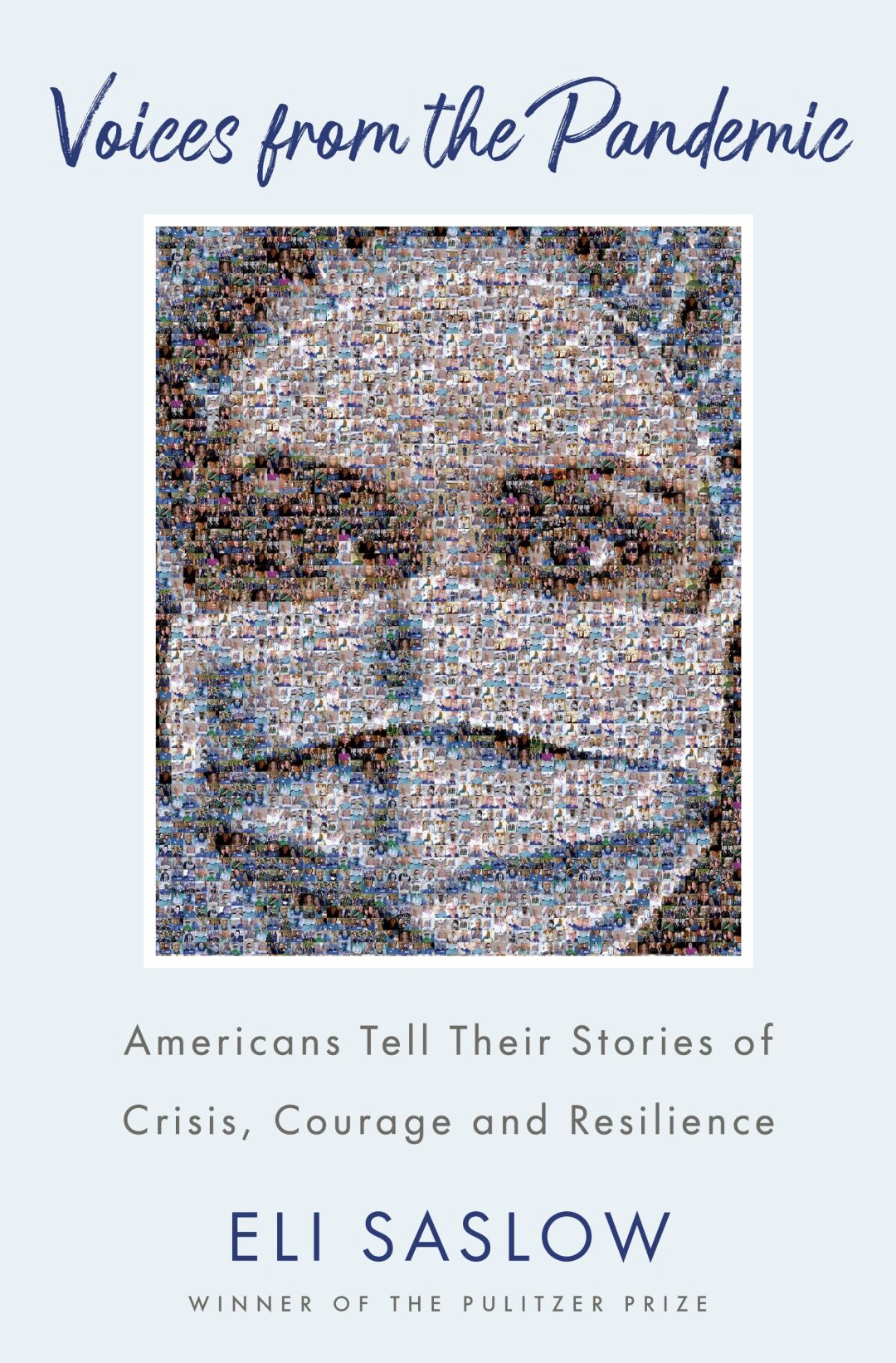

Image: Penguin Random House

BOOKS: Voices from the Pandemic by Eli Saslow “Up until a few weeks ago, I was the anesthesiologist people would see when they were having babies.” That’s Cory Deburghraeve, speaking as the intubator in a Chicago ICU in April 2020, 14 hours a day, six days a week. “They keep telling me it’s not my fault, and I’d give anything to believe that,” says Francine Bailey, after passing COVID-19 to her mother. “We’re at the mercy of the virus. We sit here and wait,” says Bruce McGillis, a nursing home resident in Ohio. These and more testaments to a year of heartbreak, loneliness, loss, and courage—

27 in all, from a coroner burying his own friends to a grandmother being evicted to a young woman 287 days into long COVID—are collected in Portlander Eli Saslow’s Voices from the Pandemic: Americans Tell Their Stories of Crisis, Courage and Resilience. It’s a rich and deeply human document of the pandemic’s extraordinary toll on all of us that somehow turns the page toward hope. —Fiona McCann

Bean Gilsdorf’s “Nov. 22, 1963 (Pink Suit series)” in Oregon Contemporary’s Time Being

Image: Conner Reed

VISUAL ART: Time Being at Oregon Contemporary After it rebranded from the Beckett-inspired “Disjecta” to the respectable-sounding “Oregon Center for Contemporary Art,” one could be forgiven for fearing the North Portland creative space was boring-bound. Thankfully, its first post-rebrand show (which ran through the summer) stubbed out any such fears.

Time Being rounded up work from Bean Gilsdorf, Lisa Jarrett, Jaleesa Johnston, Elizabeth Malaska, Maya Vivas, and Samantha Wall to explore our physical relationship with time. With through-the-looking-glass renderings of our most famous First Ladies, spools of human hair, and surreal self-portraits, the show questioned how the turning of the planet hurts, helps, and changes our bodies, and how we might best weather the transformation. In a year that could feel like a Möbius strip, Time Being was both a mirror and a guidebook, and a welcome reminder of the value in visiting a gallery. —CR