Electra Heart 10 Years Later

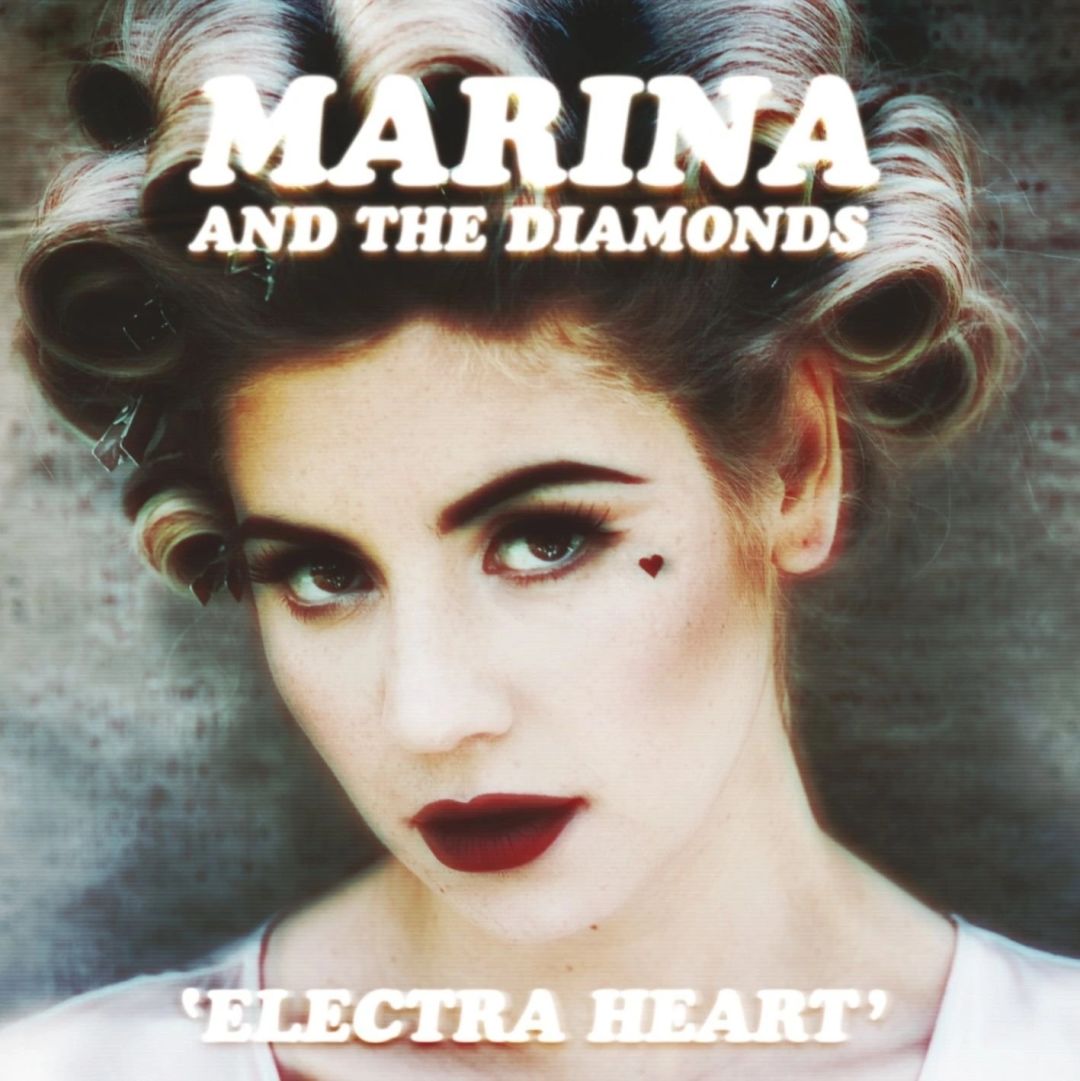

Image: Atlantic Records

Some people credit The Who or Pink Floyd for igniting their teenage love of concept albums; folks born closer to the millennium might call out Green Day’s American Idiot. Gun to my head, I’d probably tell you my inciting experience was with David Bowie, but that wouldn’t be the whole truth. The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars sunk its hooks into me eventually, but the first concept album to set my brain on fire? Take over my life? Get me doodling in the margins of my high school notebooks? That honor belongs to Electra Heart.

Released ten years ago this week, Electra Heart was recorded after its architect, Welsh alt-pop star Marina Diamandis (who went by “Marina and the Diamonds” before shortening to the all-caps mononym “MARINA”) defected to Los Angeles and soaked up its carcinogenic rays. A gleaming, candy-coated poison pill, Electra Heart ditched the Kate Nash adjacency of Marina’s debut to make a run for the radio—like any 2012 chart-chaser, Stargate and Dr. Luke show up in the production credits, and there’s an obligatory flirtation with dubstep. But quite unlike the other pure-pop albums du jour (Carly Rae Jepsen’s Kiss, Rihanna’s Unapologetic), words like “Greek tragedy” and “American Dream” got tossed around in Electra’s run of pre-release interviews as often as “goth Britney Spears.”

The idea was this: Electra Heart was Marina’s man-eating, bleach-blonde alter-ego, all dolled up like an Eisenhower-era housewife to mask the emptiness rotting her from the inside out. She had a heart-shaped beauty mark on her cheek and a death drive in her soul. “Got a figure like a pinup, got a figure like a doll / Don’t care if you think I’m dumb, I don’t care at all,” goes the album’s opening couplet, yelped over a cascading fountain of electric guitar. Elsewhere, Electra is a solid-teflon "Primadonna" and a remorseless "Homewrecker," pulling power from heartbreak until the armor slips. "Born with a void hard to destroy with love or hope," she eventually laments on the spacious, melodramatic "Valley of the Dolls" near the end of the tracklist; "Built with a heart broken from the start / And now I die slow."

You can see the teenage appeal. Electra Heart vacuumed up operatic adolescent yearning from Tumblr’s most sepia-stained corners, lacquered it in pastel pink, and spat it back in slick, punishing pop nuggets. The Paris, Texas visuals—its strongest asset—cannily tapped into “end of empire” rumblings that were growing in volume after the Great Recession and being sublimated into a brand of ultra-online teenage nihilism. “I want to explore the side [of America] that has nothing to do with glamour, and that’s all about loss and failure,” Marina said in an early-era Q&A. “But that image, that illusion we have of America really fascinates me.”

Marina was, of course, not the first person to wade into this territory. She wasn’t even the first left-of-mainstream pop star to do it in 2012 with the help of co-writer Rick Nowels. Three months before Electra Heart came Born to Die, Lana Del Rey’s burnt-out, Hollywood-steeped debut album, for which she dressed up like Jackie O. and pouted lyrics like “I’m your national anthem / God, you’re so handsome / Take me to the Hamptons, Bugatti Veyron” through a haze of narcotics. Both records resonated deeply with young millennials at the time, and both took a pretty significant critical beating.

The consensus has largely come around on Born to Die, given Del Rey’s endurance and the ways her subsequent projects have illuminated that album's objective, but we’ve done less of a post-mortem on Electra. Maybe it’s because Marina would go on to release one more solid LP before churning out two huge misfires. Maybe it’s because, all told, Electra Heart's concept turns to sand in your fingers if you grip it too tightly—it’s not quite a narrative, there’s something happening with archetypes, and Marina's posture that the dance-pop sound was a satirical stance against vapidity is dubious at best.

But what good is absolute coherence to a concept album? Who, pray tell, knows what the hell is going on narratively in Ziggy Stardust? Where Electra Heart succeeds is in mood and overall aesthetic impact: it creates a world where bubblegum and blood coalesce, where doe-eyed femininity is both weapon and shield, and big emotions reign supreme. Those big emotions help it float. Marina’s contemporaries in 2010s alt-pop cloaked themselves in cool, but Electra Heart ends with a blazingly earnest admission. “I wanna be completely weightless / I wanna touch the edge of greatness,” she sighs on closer “Fear & Loathing” (like Las Vegas!) over churning electronics. Then the kicker: “Don’t wanna be completely faithless.”

You can trace the project’s DNA to a recent crop of hyperpop heroines. Kim Petras’s designer-obsessed “I Don’t Want It At All” could well be an Electra B-side, and any number of Slayyyter tracks feel like clear successors to Marina’s sugary femme fatale blueprint. But most of that work is—intentionally—void of a beating heart. It’s avowed hard plastic, meant to delight and be disposed. What helps Electra endure is its core longing to cut through the distractions of the dream factory and gamified relationships (the album preceded Tinder by five months) to achieve real connection.

Take the aching “Teen Idle”, which flayed my depressed gay 16-year-old brain with its chorus that ends: “Wish I’d been a prom queen fighting for the title / Instead of being sixteen and burning up a bible / Feeling super, super, super suicidal.” I caught the Electra Heart tour when it came to the Aladdin Theatre in 2012, and I'm not sure I've ever been to another show that felt so cultish. The at-the-time novelty of pure pop music coming from a figure with online street cred probably helped: everyone there felt a little smug, like they knew a secret the other kids (and Pitchfork) didn't.

But the clincher, I think, was the sadness. Here was a microgeneration of people blisteringly familiar with the impulse to dress their hollowness in faux-vintage filters and construct less fallible versions of themselves to hide behind. To watch someone perform as a shiny, internet-informed character, and then see the flickers in the matrix where raw pathos poked through, was to look in a candy-colored mirror.

After the show, I met Marina, then went home and left a comment about the experience on the YouTube video for "How to Be a Heartbreaker." Within minutes, it became the video's most popular comment, and it stayed that way for the rest of the night. I felt—if I may—like the king of the fucking world. Then morning came, and someone else had taken my spot, and I felt bitter. I sulked. I wondered why the spotlight felt so good in the first place. I thought about whether I might be able to say something else that would shoot me to the top again. And I pressed play on Electra Heart.