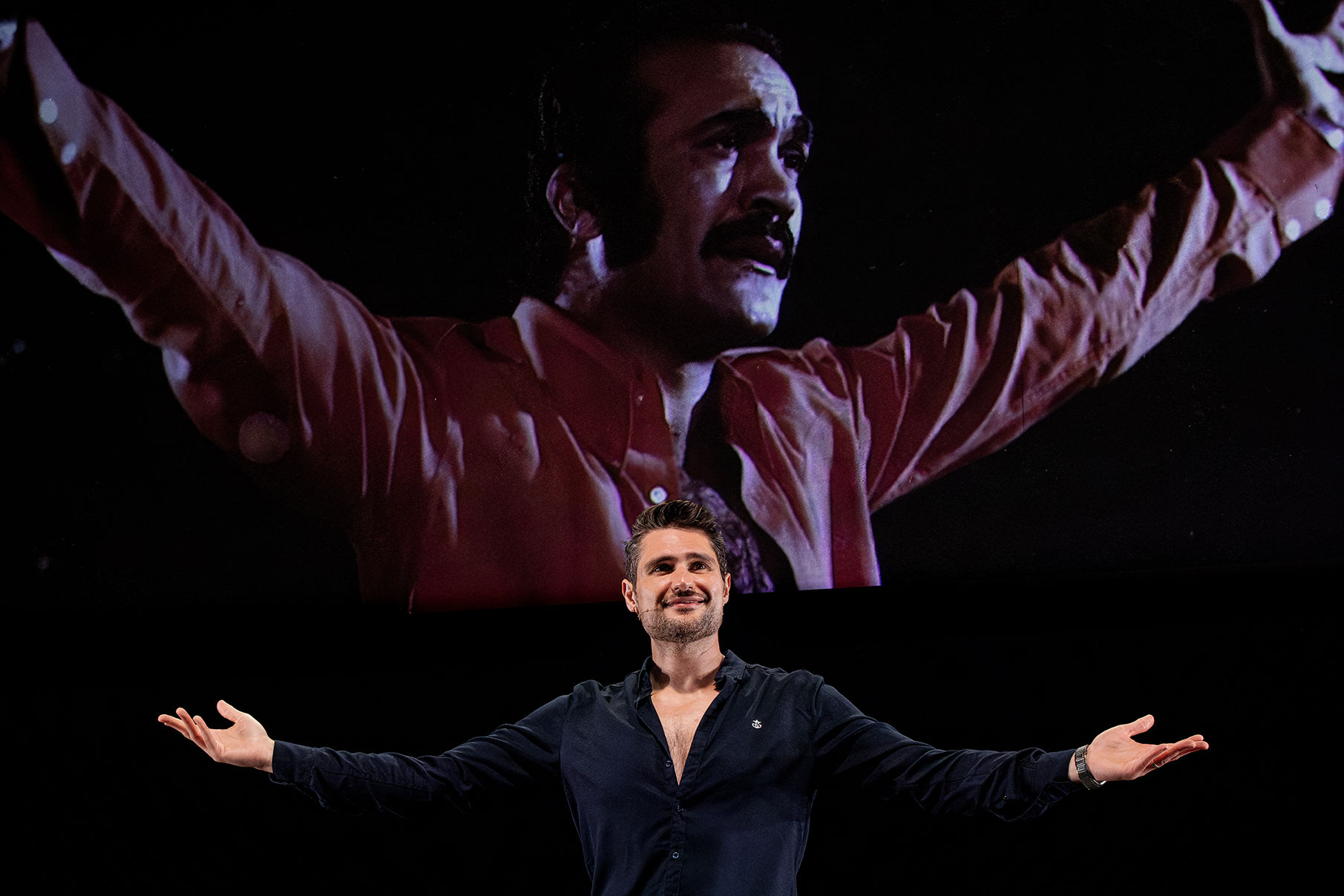

Radio III Closed TBA 2022 with Silliness and Subversion

Elisa Harkins, Zoë Poulch, and Hanako Hoshimi-Caines in Radio III

Image: Matthieu Verreault

When I started covering the Time-Based Art Festival a decade ago, one of the joys was getting to see work from across the world. Thanks to TBA, I’ve been introduced to artists from every (permanently inhabited) continent.

This year’s fest, which wrapped last weekend, looked different. In 2022, only a handful of artists traveled to Portland from outside the borders of the United States. (A tighter budget? Pandemic-related constraints? A change in curatorial priorities? I’m not sure why there’s been a shift.) But I was struck this year by the number of Indigenous artists in the lineup, ranging from Portlander Anthony Hudson, creator of much-beloved drag clown Carla Rossi, to Suzanne Kite, an Oglala Lakota scholar and artist who performed an experimental lecture that explored the relationship between colonialism and extraterrestrials.

Also on the bill was Elisa Harkins. Based in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Harkins is a Cherokee/Muscogee artist and composer who creates electronic music using Cherokee and Mvskoke languages. To the festival she brought Radio III, a collaboration with movement artists Hanako Hoshimi-Caines and Zoë Poluch. Part contemporary dance performance, part neon-saturated disco, Radio III epitomizes the kind of strange but spectacular work I’ve loved seeing at TBA over the years.

There are minimalist moments. In one stretch, Hoshimi-Caines and Poluch—dressed in white, with the stage in muted gray light—move their bodies through balletic steps and postures. There’s just a trace of a soundscape; the mood is mannered and serious.

Bookending such moments, though, are pulsing electronic beats. Early on, Harkins—also dressed in white but bathed in bright blue and pink lights—sits downstage, one knee cocked, microphone in hand, and sings serenely while gazing steadily out at the audience. “Die, don’t die, don’t die, don’t die,” she intones. It’s entrancing, a little haunting. Later, dressed in a sparkly silver shirt-waist dress—a take on a traditional Cherokee tear dress—she sings through a vocoder while spinning robotically. (In a conversation organized by the Portland Institute for Contemporary Art, Harkins explains that this character is a cyborg who’s several hundred years old and who traveled to Oklahoma on the Trail of Tears.)

Then, toward the end, Hoshimi-Caines, and Poluch don fringed pants, vests, and cowboy hats. At first, one mimics a horse as the other pretends to toss a lasso, and then they become backup dancers for Harkins, step-ball-changing behind her as she sings in Cherokee and Mvskoke. Later, Harkins drapes a fringed cape reading “LAND BACK” over her shoulders and twirls buoyantly.

It’s this swing between silliness and subversion that makes Radio III so captivating. As the trio walks the line between sincerity and cheekiness, they leave it up to the audience to decide what’s what. Yet they also extend a generous welcome. The program notes that the intention “is to create a metaphorical peacekeeping agreement between the performers in the work as well as with the people watching the piece, regardless of tribe or race.” Even as Radio III destabilizes, it’s impossible not to feel invited into its abundant joy.